My name is Albert Little and I’m a Roman Catholic. But I wasn’t born that way. Mine was a nearly decades long, sometimes meandering, trek towards the ancient Catholic Church. It began, as far as I can tell, when a Protestant pastor asked me a fateful question about the Bible and authority. It continued through my exposure to a podcasting priest and a softening of my view of the Church. And it culminated in my decision to dig deep into Catholic theology and the Early Church Fathers. All this lead me, ultimately, from Evangelicalism into the Catholic Church, and completely changed my life.

As An Evangelical

I grew up, happy and healthy, in a loving, stable home. We were nominally Christian and occasionally attended church or prayed before a meal—at Christmas or Easter—but I didn’t meet Jesus until I was fifteen. It was through my life-long best friend, himself an Evangelical Protestant, that I made the introduction and decided, then, to give it a whirl.

I’d realized, as some do at that tender age, that life was about more than just myself. The world was bigger—go figure—and seemed to be designed with a purpose. Christianity explained that purpose profoundly so I decided to commit my life to Christ, went out and bought an Xtreme Teen Study Bible, and began going to church.

I happily sailed through high school.

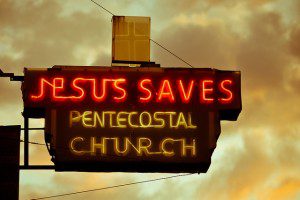

Awkward around the edges, I fell in with a crowd of equally quirky and diverse group of devout Christians who connected me to an incredible youth group at a local Pentecostal church. It was phenomenal and, in hindsight, it was one of the many graces God granted me as I grew up in my faith. At a time when many of my non-Christian friends began experimenting with drinking and drugs I found a different outlet: a group of rowdy but ultimately earnest teens who would camp out at the McDonald’s on a Saturday night to hotly debate Calvin’s view on justification; who partied with Cokes and cracked open Bibles.

Those were heady times indeed.

I was equally blessed as I began University to find a church geared towards student that met on campus. Here I not only met my future wife but a community of young adults, like-minded Christians, passionate about the pursuit of Christ. Throughout my four years of University I found myself involved in almost all aspects of the church from leading small groups, to helping with volunteer opportunities, and even capping off my stint at the church by interning the summer of my final year.

Like the strong and faithful community I’d connected with in high school, the community of my University years continued to build on what was already a strong faith foundation. A strongly Evangelical foundation.

Encountering Questions and Catholicism

It was, actually, while working as an intern that I first encountered Catholic ideas.

It was, remarkably, the pastor of the Evangelical student church, an incredibly kind and gregarious guy, who first set the clock ticking. I remember it clearly.

He called me into his office, sat me down, and asked, “What’s more important, the Bible or Tradition?”

As a good Evangelical I piped up immediately. The answer was easy, “The Bible,” I said.

“But who made the Bible?” He pressed. “God, of course,” I said.

I rapidly realized my mistake, the inadequacy of my answer, and two things dawned on me. First, who did make the Bible? And, second, why hadn’t I thought about this before.

As an Evangelical I came from a faith tradition that valued the Bible above almost everything else. God and the Bible. These were the bastions of truth for us, and God was revealed in the Bible.

But that fateful question—asked but not answered—began a series of so many more questions for me.

And began my journey into the Catholic Church.

As I dug deeper I attracted the attention of Catholics around me, and I met a few. At the time, they weren’t the kind of examples I was looking for. As a teenager I’d known bad Catholics. These were inevitably the kids you’d buy cigarettes or weed from if you were so inclined and, if anything, even the examples of Catholics I’d meet as a young adult pushed me away from the Church rather than drew me nearer but, incredibly, it was in spite of these examples that I continued to ask questions.

Tradition, I learned, put together the Bible.

Tradition in the authority of apostolic succession. The apostles themselves had appointed bishops, this was clear in the New Testament Scriptures themselves, and it was through the authority given to these bishops, who then appointed successors, and on and on, that the Scriptures were eventually discerned—and declared infallible.

But if the question of authority and the Bible was the catalyst God certainly provided further momentum.

Shortly after that fateful internship I found myself working in a factory—fairly monotonous work—and as a means to pass the time stumbled across what was then a brand-new medium: podcasting.

A Podcasting Priest and Giving the Church a Chance

It was in a humble podcast called The Daily Breakfast that I was introduced to Father Roderick, a priest from the Netherlands, and a new media pioneer. In the course of his half-hour podcast the energetic Father Roderick reviewed television shows, movies, and video games. He was a nerd, through and through, and that deeply resonated with my own interests, I’ll admit.

It wasn’t until listening to him for a week that I realized he was a Roman Catholic priest—and this blew my mind.

A priest who liked video video games? A geeky priest?

Slowly, but surely, I was unknowingly committing the first sin of conversion. I was, as G.K. Chesterton, himself a famous Catholic convert, described as, giving the Catholic Church a fair shake.

This, says Chesterton, is inevitably the first step to becoming a Catholic.

It was then—once I gave the Catholic Church a fair chance—once I realized that priests could be real people and that not all Catholics were poor examples of their faith that I began to read about Catholicism. First, through Protestant authors and then from the perspective of Catholics themselves.

And this is when a great paradigm shift began to take place.

I discovered, reading about Catholicism from Catholics themselves, something that nearly every Protestant convert before me has discovered: Nearly everything I thought I knew about the Catholic Church was wrong.

Instead, the reality of the Catholic Church, as described by Catholics themselves, was infinitely more beautiful, more incredible, and more appealing than I’d ever imagined.

My mind was blown.

It was then, in the conversion stories of Evangelicals like Scott Hahn, Stephen Ray, and an endless rotation of guests on Marcus Grodi’s The Journey Home that I began to see echoes of my own journey. My Fridays nights, after my wife was sound asleep upstairs, were spent devouring hours of conversion stories, lectures, and debates on YouTube. Or reading until my eyes were blurred.

I was a sponge and I felt, for the first time since my initial decision to follow Christ, an incredible fervor to learn more about the faith. It was insatiable.

And then I began to read the Early Church Fathers.

The Eucharist and the Early Church Fathers

I came into the Church, ultimately, in a way not all that different from thousands of Protestant converts before me. I’ve since learned this because I’ve since learned that the Early Church Fathers are a point of departure for so many of us.

In the Church Fathers, the disciples who learned from the apostles themselves, I found wholly Catholic doctrine and practice.

As an Evangelical I’d come to learn, and take for granted, that the Early Christian Church looked like the Protestant Church.

Churches were small and relatively independent. A charismatic individual was the teaching pastor and a Board of Elders oversaw the work that they did. We had no authority structure greater than our own individual church or, sometimes, our loosely affiliated denomination. And, importantly, we worshipped through coming together, singing, and hearing a motivational sermon.

This was how the Early Church worshipped as well, wasn’t it?

In reading the Early Church Fathers I was shocked.

Instead of a loosely affiliated body of Christians the first churches were closely connected to an authoritative structure. There were pastors, priests, and deacons answerable, ultimately, to a bishop who was originally appointed by an apostle of Christ. These bishops appointed successors who operated, as they saw, through the authority given by Jesus Himself.

What’s more, these early Christians worshipped not solely through singing and listening to a sermon but through a central focus on what they called, from nearly the beginning, the Eucharist. Communion. Something we shared, in my Evangelical tradition, less than once a month.

But chief among my discoveries in the Church Fathers wasn’t merely the frequency of Communion but a completely radical view of the act itself: That Jesus was actually present in the Eucharistic elements. That they became Christ.

The Early Church then, from everything I could tell, was resoundingly Catholic.

Crossing the Tiber

What began with a question from a Protestant pastor ended, at the Easter Vigil 2015, in my joining the Catholic Church.

The evidence was overwhelming. I’ve written, and will write, of all the incredible things I learned on my journey. That’s for another time.

Suffice to say, once I began convinced intellectually I became enamoured spiritually. As I began to live like a Catholic—by praying the Divine Liturgy, the Rosary, and attending Daily Mass—I fell in love with a tradition which encompasses the whole being. A beautiful ancient and always-relevant faith tradition. What I discovered was truly the fullness of the Christian Church.

There have, of course, been bumps along the way. The Catholic Church while itself perfect is not, in its members, always free from the ridiculous or benign. But, what Protestant wouldn’t want to run, arms wide open, into actual physical communion with Christ? What Protestant after learning what Catholics really believe about the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, wouldn’t be willing to trade it all for that kind of closeness?

Now, on the other side of the River Tiber, I find it difficult to imagine.