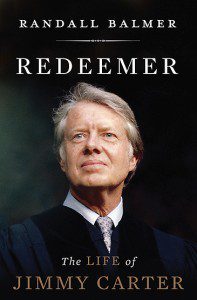

Beginning in the 1970s, evangelical voters significantly influenced electoral outcomes. Throughout the 1980s, they emerged as an increasingly- reliable Republican voting block. By the time the 1990s dawned, significant evangelical involvement in the political process meant that effectively, the Republican nomination could not be secured without their support. And, in the closely-contested general election of 2004, Karl Rove’s strategy of turning out more “values voters,” succeeded in returning George W. Bush to the White House for a second term, as more white evangelicals voted for Bush than had four years prior. Naturally, in recent years, many scholars and journalists have given increasing attention to the Religious Right. Randall Balmer is one of them.

Beginning in the 1970s, evangelical voters significantly influenced electoral outcomes. Throughout the 1980s, they emerged as an increasingly- reliable Republican voting block. By the time the 1990s dawned, significant evangelical involvement in the political process meant that effectively, the Republican nomination could not be secured without their support. And, in the closely-contested general election of 2004, Karl Rove’s strategy of turning out more “values voters,” succeeded in returning George W. Bush to the White House for a second term, as more white evangelicals voted for Bush than had four years prior. Naturally, in recent years, many scholars and journalists have given increasing attention to the Religious Right. Randall Balmer is one of them.

Randall Balmer, the Mandel Family Professor in the Arts & Sciences and Chair of the Department of Religion at Dartmouth College knows evangelicalism well. Although in adulthood he left behind his father’s faith, Balmer grew up with his feet firmly planted in Midwestern evangelicalism. As a result, he demonstrates familiarity with its nuances at a level that uninitiated scholars sometimes miss. Works such asBlessed Assurance, and Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory solidified Balmer’s place as an able interpreter of American evangelicalism, offering an insider’s understanding in a form that connects scholarly insight with a wide swath of readers, both popular and academic. Like most scholars of American Religious History, Balmer is no fan of the Religious Right. He succinctly states his assessment of the movement in the subtitle of his 2007 work, Thy Kingdom Come, opining that “the Religious Right distorts faith and threatens America.”

Randall Balmer, the Mandel Family Professor in the Arts & Sciences and Chair of the Department of Religion at Dartmouth College knows evangelicalism well. Although in adulthood he left behind his father’s faith, Balmer grew up with his feet firmly planted in Midwestern evangelicalism. As a result, he demonstrates familiarity with its nuances at a level that uninitiated scholars sometimes miss. Works such asBlessed Assurance, and Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory solidified Balmer’s place as an able interpreter of American evangelicalism, offering an insider’s understanding in a form that connects scholarly insight with a wide swath of readers, both popular and academic. Like most scholars of American Religious History, Balmer is no fan of the Religious Right. He succinctly states his assessment of the movement in the subtitle of his 2007 work, Thy Kingdom Come, opining that “the Religious Right distorts faith and threatens America.”

Based on both Balmer’s interest in the topic and the important role that a politically resurgent evangelical electorate played during the 1976 and 1980 general elections, it is no surprise that the efforts of the Religious Right figure prominently into Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter. In fact, the story bends around the early years of the Religious Right, when the Moral Majority (f. 1979) and other evangelicals joined the Reagan Revolution, helping usher fellow evangelical Jimmy Carter out of office on November 4, 1980.

Over the last several decades, scholars, pundits, and participants have offered a variety of explanations for why the Religious Right coalesced in the late 1970s. Balmer offers another: segregation. In both Redeemer and his Politico article drawn from the same material, he argues that conservative activists searched for a decade to find an issue that would galvanize evangelical voters into a reliable Republican voting bloc. When the IRS revoked the tax-exempt status of Bob Jones University because it refused to admit blacks, evangelical leaders rallied to defend BJU from “government encroachment.” Since the revocation came during his administration, Carter got the blame–even though the policy originated during the Nixon/Ford years. Although abortion became the popular rallying cry, Balmer paints it as a smokescreen, hiding the more insidious foundation of the Religious Right.

Sadly, there are many things about Balmer’s thesis which fit. The rhetoric of “states’ rights” and “governmentencroachment” certainly appealed to segregationist sentiment in the South. As Balmer points out, many in my own denomination who later supported the efforts of the Religious Right were former segregationists. Further, the machinations of Nixon’s Southern Strategy–resembling something Carter himself employed in his 1970 gubernatorial campaign (see pages 28-32)–and Reagan’s decision to launch his general election campaign with a speech lauding “states’ rights” at the Neshoba County Fair, just miles from where Andrew Goodman, Micky Schwerner, and James Chaney were murdered and buried in a berm for helping blacks register to vote during the Freedom Summer of 1964, ought to disturb contemporary conservative evangelicals. While troubling to admit, Balmer’s claims on this issue are difficult to dismiss; latent segregationist sentiment did help fuel the Reagan Revolution, including evangelical participation in it. And yet, Balmer’s monocausal explanation does not tell the whole story.

Every victorious political campaign results from building a successful coalition of unlike-minded voters. Reagan was no different, and evangelical voters supported him for a multitude of reasons. Many evangelicals, especially at the grassroots level, concerned with abortion and the erosion of traditional family structures and felt Carter (who ironically did much more than Ford on these issues) had not done enough to address their social concerns. If those issues were simply a smokescreen employed by conservative leaders to dupe rank-and-file evangelicals, the illusion quickly slipped from their control as grassroots activists acted as if they were the real issues. Finally, many Northern evangelicals looked askance on Bob Jones University, segregation academies, and other remnants of the Old South. (See Adam Parson’s take on Balmer’s thesishere.) And yet, they too, voted for Reagan at the same levels as their Southern counterparts.

Beyond reasons related their “values,” the evangelicals who voted for Reagan were not much different from their fellow Americans, often voting for him for similar reasons. After the promise and hope that accompanied the Carter campaign of 1976, the Carter years disappointed most Americans. They were dissatisfied with the economy, dissatisfied with the energy crisis, dissatisfied with the Iranian hostage situation, and dissatisfied with Carter’s earnestness that often came off as scolding. And so they turned him out of office in a landslide.

Beyond reasons related their “values,” the evangelicals who voted for Reagan were not much different from their fellow Americans, often voting for him for similar reasons. After the promise and hope that accompanied the Carter campaign of 1976, the Carter years disappointed most Americans. They were dissatisfied with the economy, dissatisfied with the energy crisis, dissatisfied with the Iranian hostage situation, and dissatisfied with Carter’s earnestness that often came off as scolding. And so they turned him out of office in a landslide.

Further, Balmer succumbs a bit to the biographer’s temptation, placing too much emphasis on Carter’s role in the formation of the Religious Right. Without a doubt, the Carter years galvanized something in evangelicals, but it was a something that was already present. Politically, their conservative “sensibilities” (HT: John Turner) were solidified in the early years of the Cold War. Recognizing this, much recent scholarship investigates the “long history” of the Religious Right, something I have written about here. Thus, it may be more helpful to think of the Carter presidency as a catalyst to the birth of the Religious Right, rather than the primary driver. Other factors, dating back to the 1940s and 1950s were seminal, establishing a political trajectory for the remainder of the century–the Carter years merely determined timing and form.

Regardless, despite my quibbles with Balmer’s monocausal explanation for the rise of the Religious Right, I heartily recommend Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter. It is Balmer at his best: depth of scholarship packaged in an immensely readable form. Beyond that, Carter’s commitment to human rights, compassion for the less fortunate, and strong work ethic ought to inspire even those on the other side of the aisle.