I’m wondering when it is possible to argue from silence when reading historical sources, and particularly in a Biblical context.

I have been writing recently on the Virgin Mary in early Christianity, and was initially taken aback to find how even I tended to attribute statements to the wrong gospel, and thus the wrong historical tradition (and I have been busy in these matters for some years). It just underlined for me the problem all Bible readers have of overcoming the “Harmony Principle” – the tendency to merge diverse statements about a topic into one connected whole.

Here’s the problem. Imagine studying an important historical individual who died in 1950. For various reasons, no biography was written for many years, until 1990 in fact. Just this last year, though, two new biographies appeared, each in its way very different from the pioneering work. The new biographies borrow heavily from that 1990 work, but expand on it very substantially. How critically should we examine those much later additions?

I mention that hypothetical example because the dates involved precisely reflect what we find in the four gospels. Jesus died somewhere around 30, but the first surviving gospel (Mark) dates from around 70. Matthew and Luke were probably written a good deal later, in the 90s. John’s text, as we have it, reflects multiple levels of composition. These stages tend not to bother us because we harmonize them, merging statements from all four indiscriminately. If however we look at those different strata separately, we get a radically different picture.

To illustrate this, think of “Mary in the Gospels,” and it is a very rich topic. It includes the Annunciation and birth story, the relationship with John the Baptist’s family, the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis, Jesus talking with the elders in the Temple – some of the most cherished passages in the New Testament. In Acts – also by Luke – Mary also appears with the Jerusalem disciples as the core of the nascent church.

Assume, though that we did not have Luke/Acts, which is the sole source for virtually all this material (Matthew has its own birth story). Assume, in fact that we had only the earlier Mark. What would we have to say then about Mary? Truly, not much, and little of what we do have is positive.

There is no birth story, except that Jesus is the son of Mary, and the main recorded encounter between mother and son is to say the least tense. Fearing he has lost his mind, Jesus’s mother and brothers come to speak with him, only to have Jesus declare that God’s followers are his real mother and brothers. If you did not know the rest of the tradition, you would assume that that was Jesus’s final severing of relationships with his biological family.

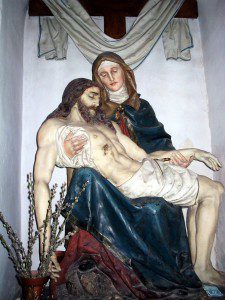

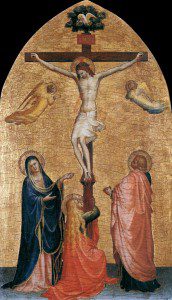

The famous scene of Mary, at the crucifixion – stabat mater dolorosa – is found only in John, and not even in Luke.

Mary features not at all in any of the epistles. (The generic phrase “born of a woman” does not count).

So let’s move away from the harmonized approach and think chronologically. Let’s deharmonize. Think back to that man who died in 1950, and assume that all through the 1960s and 1970s we have surviving correspondence from the organization he founded. But these don’t even mention his mother. We get one slight mention in the 1990 biography, but it is highly unflattering, and scarcely even hints that she played any role whatever in his career. We get a strong sense of tension and conflict, in fact. Only in 2014 or so do new books coming along, mentioning as a matter of course that the mother was in at things very literally at the beginning, that she was the first to foresee his greatness, that she had faith in him all along….

To say the least, we would wonder at the dramatic change of tone, especially at such an enormous gap in time. This is not just new information, but a total inversion of what we already knew. Yes, Luke includes the important “Who are my mother and brothers?” tale, but it has a totally different resonance when presented in a gospel that is otherwise so thoroughly Marian from start to finish. To a lesser extent, the same is true of Matthew.

Can we suggest, then, that Mary’s role in the Christian narrative is basically zero before the 70s, but that it begins a process of rapid exaltation? By the 90s, we have the Virgin Birth narrative, not to mention the astonishing apocalyptic materials in Revelation 12. (As I’ll discuss in a later post, the Revelation passage is very unlikely to be intended to refer to Mary directly, but it was rapidly adopted to those purposes). Over the following century, Mary herself is the subject of alternative gospels that draw close parallels between her and her son, in their miraculous arrival and departure from this world.

Something dramatic seems to happen around the 80s AD, even if we can’t exactly understand why.

Maybe, but one point in Luke demands notice. In highlighting some of the more extraordinary events involving Mary, he hints strongly at access to a secret tradition dating back to very early times.

I am referring to lines in which, after something remarkable has happened, like in the Birth narrative, Luke states that Mary “treasured these things in her heart, and pondered them” (2.19, 2.51). Those words seem unnecessary unless he wants his readers to think something like the following: “So, she remembered them carefully, and was able to pass them on to some other source, either in word or in writing. That must be what Luke has got access to here.”

This may well mean that Luke recognizes the novelty of his account, and feels the need to justify it to his readers, especially those who know shorter and less adorned works like Mark. Obviously, this is nothing vaguely like a modern footnote! At best, it is meant as a hint.

In some ways, the “secret treasury” idea raises as many problems as it solves. Realistically, Mary is very unlikely to have lived beyond the 40s AD, because women of that era rarely saw their sixtieth birthday. There really is no hint of any kind of written record of these events, so we are meant perhaps to suppose a group or church, located wherever, that still passed on those words as sacred tradition late enough to be heard by Luke. It would not have been in Jerusalem, where older linkages were savagely uprooted in 70AD.

So where might that have been? The stories linking Mary to Ephesus are very late indeed, and depend on a series of assumptions and logical leaps. John’s Gospel has a tradition that Jesus, on the cross, entrusted care of his mother to “the beloved disciple,” with whom she then lived. Later tradition linked this person to (a) the authorship of the gospel and (b) to the apostle John. Other traditions then taught that John himself moved to Ephesus. Hence Mary’s supposed connection to that great city. In the nineteenth century, the location of her alleged residence there was found after visions reported by a nun, and that is the site of a modern shrine.

I don’t have a solution to this issue. But I do return to my original question. How much can we legitimately read into Mark’s quite chilly lack of interest in Jesus’s Mother?

Put another way, does any source that we can plausibly date before, say, 80, frame Mary is a vaguely positive sense?

And why did the church’s attitude to Mary become so much kinder in later years, a half century or so after her son’s death?