I just received a copy of a major new book, which should be of great interest to Anxious Bench readers. Even better, I also draw attention to another and closely related text from the same hand.

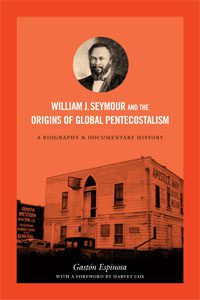

Gastón Espinosa, who teaches at Claremont McKenna College, has just published a substantial volume called William J. Seymour and the Origins of Global Pentecostalism: A Biography and Documentary History (Duke University Press, 2014).

Here is the publisher’s description:

Here is the publisher’s description:

In 1906, William J. Seymour (1870-1922) preached Pentecostal revival at the Azusa Street mission in Los Angeles. From these and other humble origins the movement has blossomed to 585 million people around the world. Gaston Espinosa provides new insight into the life and ministry of Seymour, the Azusa Street revival, and Seymour’s influence on global Pentecostal origins. After defining key terms and concepts, he surveys the changing interpretations of Seymour over the past 100 years, critically engages them in a biography, and then provides an unparalleled collection of primary sources, all a single volume. He pays particular attention to race relations, Seymour’s paradigmatic global influence from 1906 to 1912, and the break between Seymour and Charles Parham, another founder of Pentecostalism. Espinosa’s fragmentation thesis argues that the Pentecostal propensity to invoke direct unmediated experiences with the Holy Spirit empowers ordinary people to break the bottle of denominationalism and to rapidly indigenize and spread their message. The 104 primary sources include all of Seymour’s extant writings in full and without alteration and some of Parham’s theological, social, and racial writings, which help explain why the two parted company. To capture the revival’s diversity and global influence, this book includes Black, Latino, Swedish, and Irish testimonies, along with those of missionaries and leaders who spread Seymour’s vision of Pentecostalism globally.

That’s all pretty self-evident, but I particularly stress Espinosa’s diligence in assembling all of Seymour’s writings, unmediated. The global and intercultural nature of the contributions is also impressive, especially the remarks on the arrival of Pentecost in India and China.

What we have here then is basically two books, an excellent biography, and an outstanding collection of documents. This should be just a fine text for teaching.

Delighted to see it. BUT, there’s even more. Espinosa also has another promising new book, entitled Latino Pentecostals in America: Faith and Politics in Action (Harvard University Press).

Here’s the description:

Every year an estimated 600,000 U.S. Latinos convert from Catholicism to Protestantism. Today, 12.5 million Latinos self-identify as Protestant–a population larger than all U.S. Jews and Muslims combined. Spearheading this spiritual transformation is the Pentecostal movement and Assemblies of God, which is the destination for one out of four converts. In a deeply researched social and cultural history, Gastón Espinosa uncovers the roots of this remarkable turn and the Latino AG’s growing leadership nationwide.

Latino Pentecostals in America traces the Latino AG back to the Azusa Street Revivals in Los Angeles and Apostolic Faith Revivals in Houston from 1906 to 1909. Espinosa describes the uphill struggles for indigenous leadership, racial equality, women in the ministry, social and political activism, and immigration reform. His analysis of their independent political views and voting patterns from 1996 to 2012 challenges the stereotypes that they are all apolitical, right-wing, or politically marginal. Their outspoken commitment to an active faith has led a new generation of leaders to blend righteousness and justice, by which they mean the reconciling message of Billy Graham and the social transformation of Martin Luther King Jr. Latino AG leaders and their 2,400 churches across the nation represent a new and growing force in denominational, Evangelical, and presidential politics.

This eye-opening study explains why this group of working-class Latinos once called “the Silent Pentecostals” is silent no more. By giving voice to their untold story, Espinosa enriches our understanding of the diversity of Latino religion, Evangelicalism, and American culture.

I’m looking forward to reading both books.