[You can read Part 1 here if you missed it.]

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: what do I mean by the term evangelical? There are as many definitions as there are pundits trying to explain Donald Trump. And you can expect a new batch soon, now that Pew has reported 78% of white evangelical voters support the presumptive Republican nominee that many once found anathema. (Thirty-six percent “strongly support” Trump by the way, ten points more than did Romney, but I digress.) So what is this thing, this “evangelicalism,” we are talking about?

There are few things as vexing to historians of American religion (and probably their readers) than the task of defining evangelicalism. It’s an unwieldy term. Robert Wuthnow recently made a compelling argument that the “evangelicalism” of public discourse is a creation of modern pollsters. David Bebbington’s sturdy quadrilateral has faced growing critique from Mark Noll and others (I too have reservations). Yet for all the term’s shortcomings, “we are stuck with it,” Molly Worthen convincingly argues, because “to observers and insiders alike there still seems to be a ‘there’ there: a nebulous community that shares something, even if it is not always clear what that something is.”

Can we capture that “something?” Though I’ve had my doubts, I have come to believe that we can. And, like Worthen, I’m convinced that the way forward lies in “history—rather than theology or politics.”

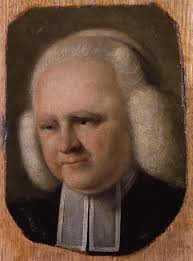

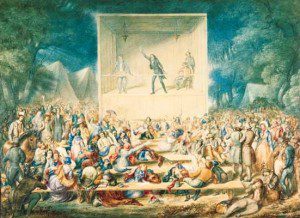

There is a broad consensus that a new religious “something”—what I call evangelicalism—appeared in Great Britain and colonial America in the 1730s and 1740s. British advocates included George Whitefield, whose preaching trips helped galvanize the movement in the colonies. In the nineteenth century, it produced revivals and exponential growth of Methodist, Baptist, and other sects. It spurred reform movements backing abolition, opposing secret societies, and promoting dietary fads. Evangelicalism spread across racial lines (though it often ironically reinforced them). It touched nearly every denomination and ethnic group. And evangelicalism’s effects are perhaps even more complex today. A historical definition must reflect this mass of people and movements spanning over two and a half centuries.

There is a broad consensus that a new religious “something”—what I call evangelicalism—appeared in Great Britain and colonial America in the 1730s and 1740s. British advocates included George Whitefield, whose preaching trips helped galvanize the movement in the colonies. In the nineteenth century, it produced revivals and exponential growth of Methodist, Baptist, and other sects. It spurred reform movements backing abolition, opposing secret societies, and promoting dietary fads. Evangelicalism spread across racial lines (though it often ironically reinforced them). It touched nearly every denomination and ethnic group. And evangelicalism’s effects are perhaps even more complex today. A historical definition must reflect this mass of people and movements spanning over two and a half centuries.

But to be properly historical, our definition needs at least four additional characteristics. First, it must be distinctive enough to have a starting point. Can we differentiate evangelicalism from what came before? Second, it must relate to some plausible causes for its existence. In other words, it must help us understand why evangelicalism emerged in the way, place, and time that it did. Third, it must embody some recognizable continuity over the span of its existence. And finally, it must accommodate development and change over time.

It’s here, I think, where Bebbington’s definition falters. Though eminently useful (including for my own thinking), it is simply not historical. If the essence of evangelicalism lies in conversionism, activism, biblicism, and crucicentrism, one is hard-pressed to differentiate it from Puritanism or another early Protestant group. Thus, it is not clear why we should mark its beginning in the mid-eighteenth century British world, rather than a century or two before somewhere else. Why also, according to Nathan Hatch, did early “Methodist growth terrif[y] other more established denominations?” Why did Whitefield and Charles Finney and D. L. Moody and William Seymour and Aimee Semple McPherson each generate such controversy? A historical definition of evangelicalism should help us answer these questions.

A historical definition of evangelicalism starts with the Enlightenment, an intellectual movement that began in the 1680s. (Not coincidentally, this is another “something” that is difficult to define, but which historians cannot seem to do without.) In Great Britain, the Enlightenment represented a growing confidence in the ability of individuals to think rationally and choose wisely. Participants harbored deep suspicions of tradition and social hierarchies, and cultivated a penchant for empirical evidence.

Evangelicalism, then, was the application of enlightenment ideas about self and society to Protestantism. And the core conviction this produced was the belief that God interacted primarily with individual believers. In today’s parlance, it was the conviction that authentic faith consists first and foremost in a “personal relationship with God.” Believers spoke to God in prayer, and God spoke back through the Bible. Moreover, God confirmed the authenticity of this faith through tangible, empirically-measurable evidence. This shift was revolutionary. Evangelicals summarily dismissed over a thousand years of tradition that held God engaged humanity as a community—the church—and established human authorities—educated and ordained ministers of the Word—for the sake of order. It also overturned the traditional evidence of faith: entrance into the church community through membership and faithful participation in the life of the church.

The emergence of evangelicalism in New England coincided with the growing importance of enlightenment ideas in other arenas of experience. Indeed, it was a perfect complement. “Do you really believe in an all-powerful God,” an enlightenment skeptic might have asked. “Wouldn’t such a being be capable of engaging believers directly? Wouldn’t that God be reasonable and benevolent, and thus want to provide evidence to anyone seeking the truth?” For true believers, evangelicalism seemed like a way to reintegrate a heterogeneous society that old Puritan forms could not encompass and the answer to nagging doubts that the Enlightenment had produced.

Thus many clergy, including some in Boston’s genteel elite, initially believed George Whitfield’s evangelicalism was an avenue to shoring up their social dominance. But this hope was short-lived. By the mid-1740s, reports of social disturbances, direct challenges to the religious and social order, and numerous church splits proliferated. God apparently spoke in a cacophony of contradictory voices. Depending on who was interpreting the Bible, it might be calling believers to submit to their ministers and social betters, or advocating political uprisings and slave rebellions, prodding attempts to walk on water, or ordering that luxury items and the standbys of Puritan theology be burned in public bonfires. In response, horrified elites concluded that respectable religion needed to be mediated by tradition, institutions, and authorities after all. Ordained ministers must be the final arbiters of God’s revelation.

Evangelicals who disagreed simply started their own churches—easy enough in a new secular nation. But such groups were usually deemed “sects” and thereby deprived of the social authority of established denominations. They typically could expect only the barest tolerance from social elites. And if they pushed too far past established norms—especially in family structure or sexual mores—even that was in doubt.

Evangelicals who disagreed simply started their own churches—easy enough in a new secular nation. But such groups were usually deemed “sects” and thereby deprived of the social authority of established denominations. They typically could expect only the barest tolerance from social elites. And if they pushed too far past established norms—especially in family structure or sexual mores—even that was in doubt.

This same basic pattern continued for the next century. Until the Civil War, evangelicalism was largely relegated to the periphery—on the literal western frontier (while it lasted) and among the populist-leaning “lower orders.” There were brief periods when respectable Protestants experimented with evangelicalism—the influence of enlightenment ideas in American life made it intrinsically appealing. But the disorder that always seemed to follow led elites back to the safety of old ways. Evangelicalism was not a fixed identity, but a fluid orientation.

I’ve focused primarily on religion in this post, and it has already gone too long, but I’ll end by noting that “respectable” Protestants’ views of evangelicalism paralleled their attitudes to other enlightenment-inspired phenomena. Take democracy, for example. Did they agree that all men were created equal? Sure (if perhaps grudgingly). Did this mean they wanted to do away with the electoral college, allow for the direct election of senators, abolish slavery, and support other democratic reforms? Not on your life. Institutions controlled by elites were the God-ordained method of maintaining the social order. They considered only those properly disciplined by church, school, government, and a well-ordered middle-class family life to be virtuous enough for public leadership.

Respectable Protestants also harbored suspicions about that other arena of enlightenment individualism: the market. They participated in the antebellum market economy without apology and did well for themselves. But nearly all agreed that unsupervised markets would destroy the social order. Repeated financial panics—in 1819, 1837, and 1857 seemed to confirm this. Once again, it fell to institutions—family, church, schools, and government—to contain self-interest and train participants in the ways of honesty, thrift, and hard work. Markets produced many fine things, but they were net consumers of virtue, rather than producers.

The puzzle that we will tackle next, is how corporate evangelicalism came to exist. How did middle-class Protestants come to the point that they could accept evangelical individualism without fear of disorder? How did evangelicalism stabilize and accommodate respectable mores? And how did the “free market” come to be associated with the production of virtue rather than the temptation to vice?

Read Part 3 to find out.