I have always deeply identified as a Christian, but it has taken me 40 years of wandering to find a church home that actually embodies a place where I holistically commune with my siblings in Christ.

I was raised on the Protestant solas, and could explain “TULIP” Calvinism by the time I was 12. But already in my teens, these particular confessions were not sitting well with my soul. I could see few signs of depravity in myself, never mind total depravity; nor could I believe in a God that was jealous, retributive, and autocratic. I sought a more experiential faith, dabbling in Pentecostal worship and Evangelical mission and service trips, but then felt uneasy about having to put on a show to prove myself a “true believer.” One practice that was always deeply moving for me was participating in Communion, but none of the churches I attended celebrated the sacrament regularly.

I started exploring Catholicism around the time I graduated from college, and quickly realized that much of what I’d been told about the largest branch of Christianity was outdated, exaggerated, or plain false canards. I loved the opportunity to withdraw from the noise of the world into the other-worldly sanctuary of the Mass, as often as daily, to spend half an hour in contemplation and communion. The relatively new Catechism of the Catholic Church seemed so much more reasonable than Calvin’s Institutes, which I had read for a college course, and no performative evangelization or improvisational prayers were required. I quickly jumped into RCIA and was received into the Catholic Church at Easter Vigil, 1998.

My first experience of receiving the Eucharist in a church that confesses the Real Presence was euphoric. I thought for a blissful moment of my early adult life that I had finally found what I’d been looking for over the past several years. But I soon realized that the fellowship and belonging I wanted so dearly—the communion aspect of the Eucharist—was practically non-existent in every Catholic parish I tried. I consoled myself with the conviction that I had the Real Presence of Jesus every time I went to Mass, no matter how little I felt like the parishioners were being the Body of Christ to each other. The Sacrament would give me a spiritual high many times, but there was no healing to be found from the psychological wounds that had been inflicted by the more fundamentalist aspects of my upbringing.

Eventually, I began to explore the more mystical corners of the Catholic tradition, as well as the social justice teachings, which had been given short shrift in the Catechism and other catechesis I had encountered. I began to use a scriptural rosary podcast to practice meditative prayer and contemplation, and discovered Mary to be a much stronger agent of the Christ revolution than the submissive statues had ever suggested. The writings of mystics such as St. Theresa of Avila, Julian of Norwich, and St. Francis of Assisi found great resonance with my spirit. Light began to shine on long-hidden wounds and long-forgotten aspirations. The Spirit was finally on the move in my life again, after about 15 years of dormancy, and it led me to start blogging in 2017.

Awake to the living inspiration of the Scriptures and Sacrament and Church, I was no longer content to listen to facile, spiritually manipulative, and even racist and sexist homilies as the condition for receiving my daily wafer of grace. I heard echoes of St. Francis’s mandate to rebuild the Church, but nothing I could build would be recognized as church by the Roman Catholic hierarchy. Because I lack a certain appendage, I could find no toe-hold of influence in today’s Catholic Church. What I did find is plenty of enthusiasts for the monarchical form of church governance, in which no one below the rank of Bishop has a voice in the direction of this “universal” church (at least not formally, but money from millionaire donors and political power talk).

The words of George Orwell, “the party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command,” resonated in my mind as I compared the Vatican’s claims to safeguard the “deposit of Truth” and receive spiritual authority and even infallibility directly from the Holy Spirit, by the will of God the Father and “institution” of Jesus, against their history of perpetrating and protecting sexual abuse, their groundless claims about the purpose and limitations of female bodies and intimate relationships, their persecution of prophets, and their millennia-long abuses of power in the name of Jesus Christ. I heeded the evidence of my eyes and ears and concluded that this wholly unaccountable, autocratic, clericalized, exclusively male, and serially abusive institutional form could not possibly have been willed by a gentle, loving God, any more than predestining persons to Hell.

It isn’t that the catholic tradition – “small c” universal and including the spiritual practices of all followers of Christ over the past two millennia, not only those curated by magisterial authorities – is deficient. To the contrary, this is the family history and collected wisdom of the Body of Christ that I believe will never be erased from human consciousness unto the end of time. I could not possibly assent to Protestant doctrines such as “sola Scriptura” or “sola fide.” But I don’t have any faith in the magisterium’s claims to exclusive or trustworthy authority anymore, either. As such, I can no longer consider myself in full communion with the Roman Catholic Church.

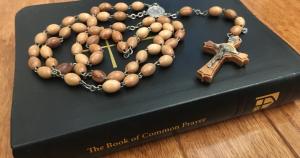

Where I have found true communion as of late is the via media of the Episcopal Church. Without rejecting the liturgical unity forged by the Catholic Church in the west, nor the lower-case catholic tradition of diverse private spiritual practices and reverence for canonized saints, the Episcopal Church has forged a reformed model of church governance that is suitable for sustaining the church in an age of literacy, democracy, science, and humanism. Authority flows from the bottom up, from parish vestries and local conventions where clergy and laity have equal voices, leaving Bishops with pastoral and presiding, not ruling, roles. And no one is excluded on the basis of sex.

While no human institution can expect to be free of abusive actors, this widely-distributed accountability and authority gives the prophetic Spirit orders of magnitude more channels to be heard in the voices of the faithful, and makes it difficult for any would-be autocrats to squelch the Spirit or continue perpetrating abuses of power for long. As an attorney by profession, with experience in lawmaking and deliberative bodies, seeing an accountable and functional governance structure is crucial for me to have trust in an institution. Less than a year after I started attending an Episcopal church, I was elected by the vestry to represent the parish at the Diocesan conference, and saw a faith-filled convention of people who were not perfect, but who were acting in good faith for the common good of the church and their communities. This is a church I can trust to do its best to be the Body of Christ in the world, to seek the Spirit’s guidance in community, and to engage in the work of reconciliation when it fails.

At the same time, I recognize the reputation of Episcopalians as stuffy white wealthy mainline Protestants. (Ironically, the first thing I voted on in the diocesan convention was a resolution to remove “Protestant” from the official name of the diocese, which dates back to 1785.) While the Presiding Bishop today is African American, and much of the growth of the Episcopal church today is found among small congregations of poor Latinos who are disaffected from both Catholic and Evangelical churches, the stereotype is not without some truth as its basis. My spirituality continues to be more Marian, more mystical, less “English” than the typical Episcopalian. I also have little affection for the matron Church of England, which is much less democratic and much more entangled with the State than its American offspring. No church is perfect; every church is made up of persons who need to keep growing in holiness and maturity, struggling against ever-present sins and weaknesses, Catholic and Episcopal churches included.

So today I call myself an Episco-Catholic. My spiritual writings will continue to be grounded in the ancient catholic tradition, not focused on the Book of Common Prayer or Anglican theologians. But I do not want to mislead anyone into thinking that I am concerned with maintaining the orthodoxy defined by the Vatican either. I greatly respect my Catholic brethren who likewise believe in a Mystical Church that is indefectible despite its fallible leadership, and support their efforts at structural reform, without holding my breath that we will see any meaningful improvement in my lifetime. And I dream of the day when all Christians of good faith can share in one Communion of the Eucharist and of Saints, without being hindered by exclusionary human institutions.