—– To purchase, go to the bottom of the page —–

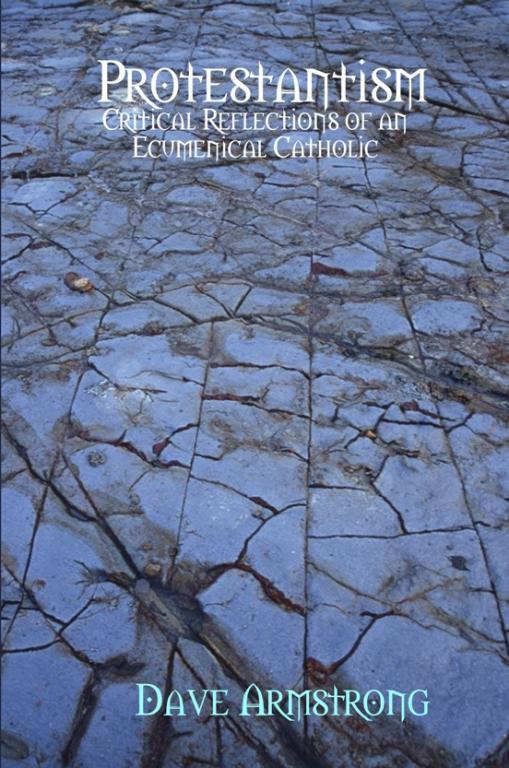

[Lulu cover design by Dave Armstrong]

Table of Contents

Dedication

Introduction

I Sola Scriptura: The Bible as Ultimate Authority

II Doctrinal Diversity and the Invisible Church

III The “Pure” Church, Devoid of Sinners

IV Private Judgment

V Church History

VI The Perspicuity (Clearness) of Scripture

VII Predestination, Calvinism, and Arminianism

VIII “Dead” Catholics and Rituals, Etc.

IX Martin Luther and Protestant Origins

X Faith and Works

Appendix 1 John Calvin on Protestant Divisions

Appendix 2 The Agony of Luther, Melanchthon, and

Bucer Over the State of Early Protestantism

Appendix 3 Luther’s Assertions of His Own Authority

Appendix 4 Erasmus on Luther and Protestantism, and

Luther on Erasmus

Appendix 5 John Henry Newman on ProtestantismApostolical Tradition, 1836

On the Abuse of Private Judgment, 1837

Private Judgment, 1841

St. Athanasius’ Rule of Faith, 1844

Faith and Private Judgment, 1849

Introduction

The numbered structural format of this book is modeled after the classic work by the French mathematician, physicist, and Catholic apologist Blaise Pascal, Pensees (“thoughts” – 1662). My intention is to critique various aspects of Protestantism, in the manner of “sayings” (272 total) – a literary technique used to great effect by our Lord Jesus Christ, St. Francis of Assisi, Confucius, Martin Luther, and Socrates, among many others. The generalizations used in this method are not meant to imply that there are no”exceptions to the rule.” They are simply broad observations of Protestant ideas and tendencies.

My intention is not to insult or to excite needless quarreling. This material is not meant to be an attack on the merit and personal character of present-day Protestants, but rather a very straightforward and critical examination of various aspects of Protestant theology and the formal principles of Protestantism, as well as some of its negative tendencies in practice.

I wish to emphasize that I have much respect for many, many Protestants, and the great deal of truth and noble, praiseworthy goals and aspects of their beliefs. This is a loving (if vigorous) “in-house” critique from a brother in the Lord, not a “hit piece” by an “enemy.” I was, after all, a Protestant for the first thirty-two years of my life, and I fondly remember that time.

Deep feelings of partisanship and allegiance are, of course, present in all seriously committed Christians. I only ask the Protestant reader to accept my good faith and to believe that I bear no ill will towards non-Catholics in general. I simply – as a Catholic – disagree with some things. I hope that I can be received as an honestly critical “friend” and fellow Christian, albeit across a rather large and unfortunate chasm.

True ecumenism, to which I am passionately committed, does not “paper over” profound disagreements in a delirious, “warm fuzzy” atmosphere of self-deluded bliss. Rather, the profundity of authentic ecumenism is fellowship despite major differences, in a special and delightful environment of mutual respect. I maintain a deep love and respect for my “separated” Christian brethren. And I offer these reflections in that spirit.

Excerpts

13. The Bible doesn’t teach that it is the final authority in Christianity, in terms of it being in opposition to apostolic Tradition and the Church. All the teachings of the Bible are true, and Catholics (and Orthodox) affirm them. It is the unnecessary, unscriptural, and illogical step from these affirmations to the proposition of sola Scriptura with which we disagree, since the Bible itself speaks explicitly of both a true divine, “received” Tradition and of the binding authority of the universal, institutional Church, and the very canon (the “stuff”) of the Bible was authoritatively determined by the Church. Therefore, the three interrelated concepts cannot be separated, any more than can the three dimensions of a cube, even in a hypothetical scenario in which all we had for “data” was the Bible.

51. I think God cares enough about doctrinal truth to guarantee its continued existence in some incarnated Body of Christ, through history. I don’t think God is a doctrinal relativist, enthralled with doctrinal “diversity.” That is pure liberalism. It’s one thing to have honest differences that we work through as Christians; quite another to start saying that such differences are normative, to be expected, and actually condoned by both Scripture and the early Church.

102. To entirely blot out sin, God would have had to prevent the fall itself, and start the human race all over. Once sin is allowed into human existence, then there will be corrupt popes, just as there were corrupt Bible-writers (Peter, Paul, David, Moses: a betrayer, three murderers and an adulterer).

113. It is said that those who convert to Catholicism based on historical considerations interpret Church history for themselves as they go through the process of conversion. To an extent this is true, but no more (in essence) than the Fathers when they said “the Church has always taught thus-and-so, and if you deny that you are a heretic.” It is an acceptance of a certain set of teachings that has been passed down through history (and can be verified), as opposed to determining what one will believe about doctrines x,y,z, as if that were permissible, given the history of doctrine. The convert is accepting what has been passed to the Church and them, not making up their own mind at every turn. We don’t reinvent the wheel every generation in the Church.

150. One can readily accept the distinctions among early Protestants (Anabaptist vs. Reformed/Lutheran), and acknowledge that the former were much more anarchical from the start, whereas the latter maintained some semblance of Tradition and apostolic continuity (albeit “skeletal” from our vantage-point). On the other hand, we can also maintain (as I strongly do) that the principles which made rampant sectarianism historically inevitable (perspicuity, private judgment, absolute supremacy of the conscience, sola Scriptura, a certain anti-sacerdotal and anti-episcopal bent, iconoclasm, philosophical nominalism, etc.), were indeed consciously present from the beginning and can be regarded as initial causes for the later history.

158. By and large, Catholics think the Scriptures are clear, yet need a binding interpreter in the end, and that the Fathers are largely clear, but need a Church and councils to determine where they are wrong in particulars. Many Protestants, on the other hand, seem to think that the Fathers are very unclear, and the Scriptures very clear, without a need for a binding Church authority. Yet they can’t come to an agreement.

184. Calvinists say it is the human’s fault that he is damned by God from all eternity, and it is grace and mercy for God to save any from such a horrible fate, since they are all in the same boat. So which is worse (or more plausible): a human’s fault that he is damned, while his friend can go to heaven, neither having any choice in the matter at all, or a human’s fault that he doesn’t choose (by God’s grace) to accept the grace God freely offers to all? God cannot cause evil, and fallen man cannot save himself.

Purchase Options******

Last updated on 3 June 2023