The sermons, essays, and speeches of The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. are a wonder to behold for their rhetorical prowess. Richard Lischer, in his book, The Preacher King (Oxford University Press, 1997), explains how King drew together many strands to weave his compelling rhetoric.

Raised in Ebenezer Baptist Church, King experienced the power of black preaching.

His seminary training in Protestant liberalism gave him the tools of critical thinking. He also had a keen understanding of the power of American civil religion. King fused all of this into his unique homiletical style. This enabled his rhetoric to comfort and inspire the black congregations to whom he spoke. At the same time, he was able to draw in sympathetic whites to the cause of liberation. He did this by appealing to their ideals of liberty, justice, and American patriotism.

For example, Martin Luther King’s Christmas Sermon demonstrates the interconnectedness of all peoples in a compelling way. The famous I Have a Dream speech helped listeners to see the God of history drawing the cause of desegregation into the great arc of history that “bends toward justice.” And his sermon on the Drum Major Instinct is a perfect example of using a common image – a drum major – to brilliantly illustrate egoism and its destructive consequences for individuals and societies. With incredible skill, King used metaphors, images, concepts and ideals to preach on oppression and liberation that had the ability to reach both oppressed and oppressor.

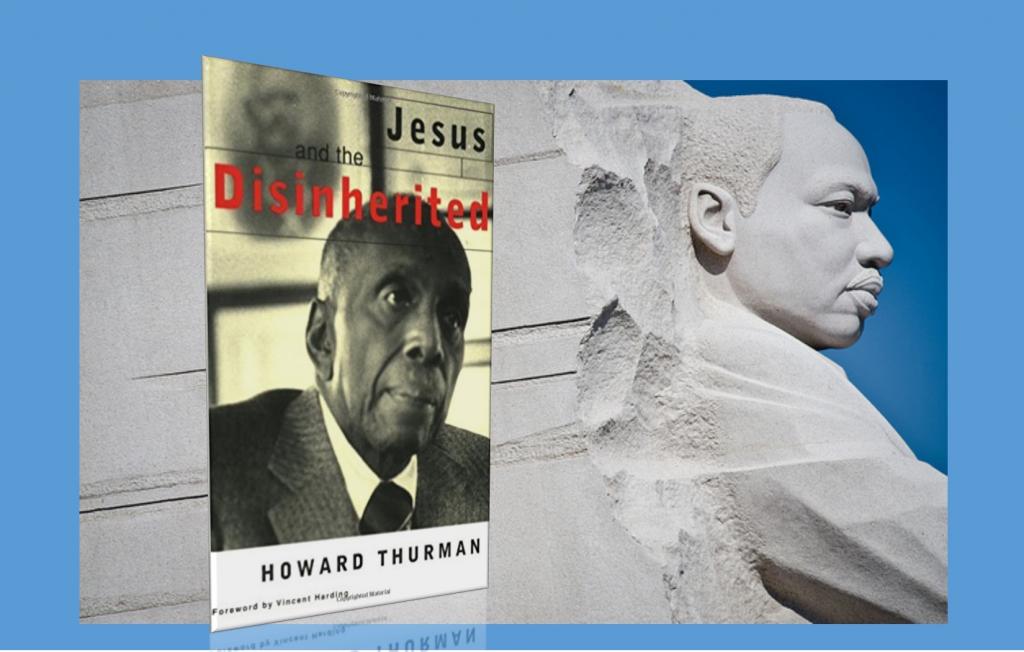

One of the major sources of inspiration for Martin Luther King was the theologian Howard Thurman (1900 – 1981).

King was said to have carried Thurman’s 1949 book, Jesus and the Disinherited, with him to his dying day. Examining this book will help us see how Thurman’s biblical exegesis and black theology influenced King.

In other words, to understand Martin Luther King, you need to read Howard Thurman.

The idea for Thurman’s book came from a conversation he had with a man in Ceylon, India. The man questioned how Thurman could still be a Christian knowing that Christianity was used to justify the institution of slavery that had kept his ancestors in bondage for generations. That same religion continued to keep American blacks oppressed through segregation and Jim Crow laws.

Thurman chose answer the man’s challenge to justify his faith by using a method of disputation similar to that of Thomas Aquinas’ dialectical reasoning. He states the question, and names all the reasons for a negative answer. But then he affirms a positive answer by showing how a correct understanding of doctrine (in this case, the “religion of Jesus,” as Thurman calls it) provides the means for arriving at an answer that affirms faith.

Thurman describes the “disinherited” as those with their “backs against the wall” whose survival is daily in doubt.

Always the same question persists for the oppressed. Under what terms is survival possible? What Jesus endeavored to demonstrate is how to find a way out of internalized oppression. This teaching, Thurman insists, is absolutely applicable to Blacks today. Because if one’s attitude toward one’s oppressor, one’s fellow oppressees, and oneself is not aligned with the will of God, the risk of self-destruction from within grows exponentially.

This leads Thurman to confront the three “hounds of hell” that pursue the disinherited — fear, deception and hate.

Each of these maladies are gross distortions of self-protection. These survival mechanisms adopted by the disinherited can, ironically, become the sources of their own undoing. For example, fear is useful to protect against danger. And hatred is the means by which the oppressed preserve their core of identity and prevent moral disintegration. But when persistent, systemic and overpowering fear and hatred are part of everyday life, something happens. The habits built for self-preservation turn out to be the stepping stones on the road to destruction. Violence and addictions, for example, are symptoms of this internalized oppression.

Thurman argues that Jesus was one of the disinherited.

This meant that Jesus’ teachings are not just a resource for survival. They actually bring about the means of flourishing, even in the midst of oppression. Applying the lens of black theology to scriptural exegesis, Thurman provides a solid argument to embrace the religion of Jesus. Thurman insists that the religion of Jesus transforms the demons of internalized oppression into the means for grace, hope, and empowerment for change.

One can imagine Martin Luther King reading Howard Thurman again and again. He needed to remind himself how to bring together Scripture and a hermeneutic of liberation.

Thurman’s theology provided the framework for King to pastorally address the crowds of his oppressed brothers and sisters. They longed for a Word that would help them through “one more day.” Inspired by Thurman, King was able to give them that life-sustaining Word.

Of course, there came a point in King’s ministry and civic engagement when his rhetoric became much more caustic, definitive, and prophetic.

Martin Luther King came to realize that the powers of racism and oppression were much more entrenched and virulent than he had anticipated. We can detect this shift in his rhetoric especially during the last three years of his life. In his work with the Poor People’s Campaign**, and in his critique of American militarism, his soaring and hopeful prose took on a sharper, jeremiadic tone. As he learned from Thurman, sometimes a good sermon is simply not enough.

“Obviously, then, merely preaching love of one’s enemies or exhortations – however high and holy – cannot, in the last analysis, accomplish this result. At the center of the attitude is a core of painstaking discipline, made possible only by personal triumph. The ethical demand upon the more privileged and the underprivileged is the same.” (106)

In many ways, King’s life mirrored that of the Savior to whom he committed his life. Jesus began his ministry with an openness to engaging and (sometimes playfully) conversing with all manner of peoples, even those in oppressive positions. King did the same.

But just as Jesus the disinherited moved toward Jerusalem and his crucifixion, King the disinherited moved toward Memphis and his assassination.

Jesus’ engagement with the Powers was more and more direct the closer he came to the center of the beast. He overturned the moneychangers’ tables. He engaged in heated exchanges with religious leaders. And he spoke directly with Pilate himself. Jesus minced no words and spared no prophetic action. Similarly, Martin Luther King’s tone in his writing and speaking became much more prophetic, directly criticizing those who exercised authority and power in oppressive ways.

And, sadly, like Jesus, King’s life was cut short. His murder happened just he was in the thick of naming and unmasking the Powers for what they really were. They are the evil of the Domination System (in the words of Walter Wink). And it appeared they had defeated the man of God.

But death to the man does not mean death to the cause of justice.

Our task today is to take up that cause with just as much fervor as Martin Luther King. We face yet another rising tide of white supremacy and normalized racism. Not to mention a president who disparages non-whites at every turn. So our challenge is pressing. We must confront police brutality toward black and brown bodies. The criminalization of skin color. And the dehumanization of entire countries deemed “holes for excrement.” Such rhetoric and policies require an equal and opposing force for prophetic justice. Today there is just as much need for the dismantling of the power structures that keep both oppressed and oppressor in thrall.

Thurman explains how the religion of Jesus can show the disinherited (and their allies) how to break the patterns of self-destruction and self-hate.

Instead, we can embrace the redemptive and life-giving religion of Jesus. This religion converts the heart of the believer from the inside out, no matter what oppressive circumstances press in from the outside. Through profound biblical exegesis, Thurman shows Jesus’ self-understanding as a beloved and precious Child of God. Jesus then enables others to experience this belovedness for themselves through his teachings, miracles, healings, and the resurrection itself.

As a result, the disinherited can indeed cling to the religion of Jesus without hesitation. We can draw upon its transformative love to withstand the onslaught of oppression and take up the cause of liberation.

May we, like Martin Luther King, draw on these words of Howard Thurman.

“The disinherited will know for themselves that there is a Spirit at work in life and in the hearts of [all people] which is committed to overcoming the world.” – Howard Thurman

**The Poor People’s Campaign has been revived by The Rev. William Barber. To join the national call for a moral revival click here: https://poorpeoplescampaign.org/

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is an ordained minister in the Lutheran Church (ELCA).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/.

For more of Leah’s reflections on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., racism, white privilege, and justice:

Preaching King’s ‘Drum Major Instinct’ in the Trump Era

The Harp Sermon: a Response to Charlottesville and Racial Hatred

Preaching Hagar and Ishmael when Philando is on Screen

Watching ‘Blade Runner’ (1982) in the Age of Black Lives Matter