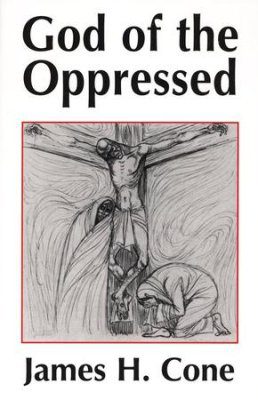

The eminent black liberation theologian James Cone has died at the age of 79. It feels to me like a shining light in the moral universe has just gone out. His work has been critical for my development as a theologian and homiletician. Cone’s books were turning points for me as a person of whiteness who needed to understand just how that whiteness impinged upon my scholarship, preaching, teaching, pastoring, and place in society.

Cone’s book, God of the Oppressed, helped me understand that all white theologians must be read with a hermeneutic of suspicion.

This is because of our inability to comprehend what life is like for blacks in this country as the descendants of slaves dealing with the effects of internalized oppression. For Cone, all the theological lions from Barth to Tillich are suspect because they are unaware that their supposed knowledge of God is corrupt by being white and oppressive.

From Cone’s perspective, God’s revelation to blacks and other oppressed peoples is the only valid revelation. He provocatively proclaimed that “Jesus is black.” This was a shocking statement to make in 1975 and even now in 2018. But it makes sense, because Jesus so closely identified with the poor and oppressed Jews in his own time, he is also Black today because that is the population who has endured the most suffering in this country. (Although I would add that First Nation tribes have endured – and continue to suffer – at least equal shares of suffering at the hands of whites, albeit in different forms.)

Cone’s writing taught me that the ethical dimensions of our knowing (epistemology) have important implications for our discourse about our relationship with God and each other. Those questions regard the who, what and how of epistemology.

Who gets to determine what is “real” knowledge?

Up until the late twentieth century, the realm of knowledge was guarded by white European men with considerable wealth and control over who was excluded from theological discussions (women, colonized people, the poor, etc.). Thus a self-reinforcing circle of elitist knowers determined that anything which deviated from the purely intellectual, dispassionate, supposedly objective means of obtaining knowledge was suspect at best and necessarily disregarded at worst. The reason is because they have been insulated from the ways in which their epistemology justifies the othering, denigration, subjugation and even annihilation of women, people of color, the poor and the marginalized of this world.

Where is knowledge located?

The where of epistemology has two dimensions for black theologians. One is the internalized and highly personal knowledge of the self. The other is within the community of believers.

Cone began his book, God of the Oppressed, with an outright statement of the personal and sociopolitical factors that inform the epistemology of his theology – how he has come to know what he knows about God. According to Cone, it is the theologian’s personal history that serves as the most important factor in shaping the methodology and content of his or her theological perspective. Thus he urges theologians to be more up front about the nonintellectual factors that are so important for the opinions they advance.

Cone’s personal location in the black church of white-dominated America was a prime informant of his theology. He described the “mental grid” of his theology within the context of a people who have been enslaved, lynched and ghettoized. It also gave him the moral and ethical ground to criticize white theologians who are blind to the way their sociopolitical location upholds the very structures Jesus despised. For Cone, only those who speak from the very place where Jesus located himself – at the point of capture, torture, suffering and death – have epistemological access to the theological resources for knowing Christ and God.

Cone’s work helped me as an ecofeminist theologian to go a step further.

I came to the realization that theological knowing is also located in bodily knowledge for women in both suffering and humiliation, as well as visceral joy and the celebration of the incarnation. Feminists argue that the intensely localized knowledge of women through their experiences of sexuality, childbirth, rape, abuse, and intimate love, are important sources of theological reflection, especially in light of God’s decision to incarnate as a fully fleshed human being.

Ecological theologians insist that knowledge of God is also located in the suffering of the planet – it’s ecosystems, species driven to extinction, and waters that can no longer sustain life. Thus the intersection of ecology and feminism – ecofeminism – is a nexus of divine revelation precisely because of the ways in which females and the natural world share in mutual suffering.

The other dimension of the where of black theological epistemology is within the COMMUNITY of the oppressed.

What the slaves and their descendants came to know about God was mediated not just through their common experience of bondage and oppression, but also in the black church. Spirituals, the biblical hermeneutic of liberation, personal testimonies, spirited prayers and prophetic preaching proclaimed a gospel of hope, God’s love, and faith-survival skills to help sustain them for “one more day.”

This was in direct contrast with the epistemology of the white church which declared the stories, practices and beliefs of the black church to be suspect for supposed superstition and being heathen and “uncivilized.” In resistance to this oppressive narrative about told about them, the community of Black believers lifted each other up, and supported each other. They developed codes for communicating that went right over the heads of their white masters. They also held each other accountable in cases of “back-sliding” and sinfulness.

How should whites continue our discourse about what we can know about God, given what Cone has taught us?

Cone is very clear that in order for whites to know anything about the God of liberation, they must adopt a position of uncharacteristic humility and learn from their black brothers and sisters who this God is. No longer can whites assume a position of superiority in the theological realm. They have lost the moral authority to claim any knowledge of God. Only by submitting to the teachings of the black church and converting to the struggle for black freedom and against white oppression, can whites hope to be invited – and provisionally accepted – into this struggle for freedom.

Chief among the how of black liberation theology is to interpret Scripture through the lens of liberation for oppressed people. This is why the story of Exodus is a prototype for understanding the black struggle for release from slavery and entrance into a promised land.

There is much more that should be said about James Cone.

This is just one testimony of one white woman whose heart was convicted and whose eyes were opened by the work of this theologian. My colleagues and I at Lexington Theological Seminary encourage our students to read Cone and wrestle with the implications of his black liberation theology for their own ministries in the church. Most recently I had students in my covenant group read a chapter from his last work, The Cross and the Lynching Tree. Cone’s writing generated much rich discussion among our racially-diverse group about how our knowledge of the ongoing suffering of the black community must fundamentally shape the conversation of the church for justice.

I am grateful to James Cone for giving me and so many others the theological and epistemological tools we need for confronting racialized evil, standing in solidarity with its victims, and allowing God to work with, in and through us to effect resurrections after the crucifixions.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is an ordained minister in the Lutheran Church (ELCA).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/.

For more of Leah’s reflection on race and theology:

The Healing Power of ‘Moonlight’: Race, Erotic Love, and Baptism

Watch Night with Simeon and Anna: Recommit to Racial Justice in 2018

8 Ways to Preach About Charlottesville, White Supremacy, and Racial Justice