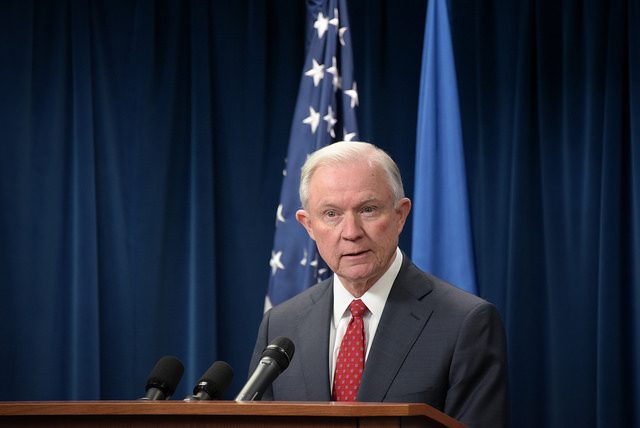

Hundreds of United Methodist clergy and church members signed a letter bringing church law charges against U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, himself a member of the Methodist Church. Among the many charges are accusations of child abuse in reference to separating children from their parents accused of illegally entering the U.S. and holding them in “mass incarceration facilities.” The group also accuses Sessions of racial discrimination and “dissemination of doctrines contrary to the established standards of doctrines” of the United Methodist Church.

In addition, the letter cites his “misuse of Romans 13 to indicate the necessity of obedience to secular law, which is in stark contrast to Disciplinary commitments to supporting freedom of conscience and resistance to unjust laws.”

This is a bold, unprecedented move.

But is it right for the church to critique one of its own and threaten spiritual discipline? For that matter, when any clergy publicly critique those in power, are they violating the separation of church and state?

I’ve conducted research and am writing a book called Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red/Blue Divide, so these questions are important to me. I surveyed over 1000 mainline Protestant clergy about how they think and feel about addressing controversial issues in the pulpit. Many of the respondents were Methodist. And their varied responses confirm that the relationship between religion and politics continues to be fraught in this country.

But it’s important to make a distinction about the principle of the separation of church and state.

This phrase is based on Thomas Jefferson’s metaphor of a wall of separation between religion and government. He used this image to describe his interpretation of the First Amendment that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof...” To be clear, while there is ongoing debate about the relationship between government and religion, the First Amendment was intended prevent the establishment of a state church. It did not state that churches could not address issues that involve government. Thus, for example, it would be inaccurate to accuse a preacher of violating the separation of church and state by preaching a sermon that addresses issues of public concern. It may make folks uncomfortable, but it does not violate the Constitution.

The Methodist clergy, then, have not violated the separation of church and state by bringing charges against Sessions.

But is the church “meddling” in affairs that should not concern them?

As a Lutheran, I turn to Martin Luther’s Catechism for guidance. Luther gave instruction on the Ten Commandments – particularly the commandment about honoring father and mother – that can be applied to this dilemma.

When we read the Ten Commandments today, most people only think of them as a set of rules for the conduct between individuals. But these commandments were a direct result of a nation and its leaders exploiting people, stealing their freedom, stealing their labor, punishing anyone who dared speak out against them, and demanding obedience as if the ruler himself were God. Pharaoh and the Egyptians squelched any effort of the Hebrew people to practice their faith, and committed genocide by murdering their children.

So God is very clear that the Hebrew people freed from slavery are to build their nation on rules and expectations that everyone must abide by – including and especially the leaders, the ones who are charged with the care of children, and anyone who has authority and power, whether it’s a parent, a tribal leader, an attorney general, or a president, for that matter.

Luther explains this in his Large Catechism when he discusses the Fourth Commandment to honor father and mother.

For Luther, this commandment is not limited to parents by blood, but extends to all who have responsibility for the care and governance of others. This includes teachers, employers, and government leaders. Luther is clear that we are to show honor, be obedient, and respect those who have charge over us.

But here’s the thing – Luther also says that this commandment carries equal expectations for those in power.

He says:

In addition, it would also be well to preach to parents [and, by extension, those who have the role of leader] on the nature of their responsibility, how they should treat those whom they have been appointed to rule. . .

For God does not want scoundrels or tyrants in this office of authority . . . They should keep in mind that they owe obedience to God, and that, above all, they should earnestly and faithfully discharge the duties of their office, not only to provide for the material support of their children, servants, subjects, etc., but especially to bring them up to the praise and honor of God. Therefore, do not imagine that the parental office [or the senatorial office, or the CEO office, or even the presidential office] is a matter of your pleasure and whim. It is a strict commandment and injunction of God, who holds you accountable for it. [1] [Bracketed material is my own.]

So if God holds leaders accountable, and the church is responsible for conveying the teachings of the Bible, then, yes, the church is within its rights to hold leaders accountable.

Luther goes on to say, “the real trouble is that no one perceives or pays attention to this. Everyone acts as if God gave us children for our pleasure and amusement, gave us servants merely to put them to work like cows or donkeys, and gave us subjects to treat as we please, as if it were no concern of ours what they learn or how they live. No one is willing to see that this is the command of the divine Majesty, who will solemnly call us to account and punish us for its neglect.”[2]

This was exactly the case for those with power and authority in Israel who did not always carry out their duties in accordance with these commandments. So God sent prophets from time to time to point out where there were discrepancies between the actions of the leaders and the commandments of God. Always the prophets spoke on behalf of those most vulnerable – widows and children, the poor, the foreigner, the resident alien, and those with no power in a system that was becoming just like the oppressive nation of Egypt that had enslaved all of them generations ago.

Of course, the leaders hated when the prophets spoke.

Read about Elijah, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos, Micah. Read about John the Baptist and Jesus in the Gospels. They were all told by the leaders and even by their fellow citizens to sit down and keep their mouths shut. But no matter how they were pressured or threatened, and no matter how much they suffered, they would not back down from critiquing the leaders, and the systems of government, and the religious hierarchies, and any aspect of society that was exploiting the vulnerable. They never backed down from holding them accountable to God’s commands.

Last year, Lutherans marked the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther, another prophet, if you will. Just writing the Catechism was a radical act for its day. Most of us were taught to think about the Catechism as a morality document. And that is certainly part of what Luther intended.

But there is a revolutionary aspect to the Catechism that people often forget or want to gloss over.

You see, educating people about what God expects not only for them, but for their religious and secular leaders – this is a form of resistance to tyranny. Because an educated population is a population that is not so easily controlled. That’s why they tried so hard to silence Luther with court trials and excommunication. They were worried that pretty soon not just this one monk, but everyone would start rising up against tyranny. And, indeed, that’s what happened.

In today’s churches, many people still feel uncomfortable when they hear a prophetic sermon. Some people insist it’s not appropriate to talk about public issues in the pulpit.

But I can tell you – for the person who is living with oppression, for the person who is being targeted and exploited by those who are abusing their power, for the poor, for the foreigner, for the children in cages separated from their parents who are seeking asylum in this country – the voice of the church is vitally important. They are praying for someone to speak out on their behalf. They are longing for a representative of God to see them, recognize their pain, and call to account those who are holding them captive, and then working to set them free.

If pastors and their parishioners refuse to apply the commandments to the justice issues of their day, if clergy are expected to never engage or critique those in power, then they become nothing more than “chaplains of empire,” instead of being ministers of God’s prophetic gospel.

A friend of mine sent me a picture of a group of men in Germany – the land of Luther – standing at attention saluting with the seig heil. And they were all wearing pastor’s robes and clergy collars. It made me ask myself – will I be a chaplain of empire or a preacher of the gospel?

The Ten Commandments are given to us because of God’s Divine love and care for everyone. They exist to protect relationships: relationships between parents and children, between family members, between friends, between citizens and their elected leaders, between human beings and the very planet itself.

So, yes, I believe the United Methodist Church is right to hold Jeff Sessions accountable for what he is doing.

The Rev. David Wright, a Pacific Northwest Conference elder and chaplain at the University of Puget Sound in Washington State, and organizer of the effort to charge Sessions, says he hopes that the action prompts Sessions’ pastor to talk with him.

As quoted in an article by Sam Hodges, Wright said, “I hope his pastor can have a good conversation with him and come to a good resolution that helps him reclaim his values that many of us feel he’s violated as a Methodist.” He added: “I would look upon his being taken out of the denomination or leaving as a tragedy. That’s not what I would want from this.”

Indeed, the hope and prayer is that Sessions’ heart and mind will change. And that all those associated with and supportive of this violation of human rights will also change. The church has a role in this process. By taking these actions of spiritual discipline, the church is fulfilling one of its major functions as an instrument of God’s love, peace, reconciliation, and mercy in the world.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is an ordained minister in the Lutheran Church (ELCA).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/.

See also:

Mr. Trump, Here’s What’s Wrong with Calling People ‘Animals’

No, Mr. Pruitt, Fossil Fuels Are Not God’s ‘Blessing’ for Humanity

[1] “The Large Catechism: The Ten Commandments”; The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Lutheran Church, Edited by Robert Kolb and Timothy J. Wengert (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2000), 409.

[2] Ibid. 409 – 410.

[3] “Discipleship and Spirituality According to Luther’s Catechisms,” Edward H. Schroeder, Together by Grace: Introducing the Lutherans, edited by Kathryn A. Kleinhans (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 2016), 41.