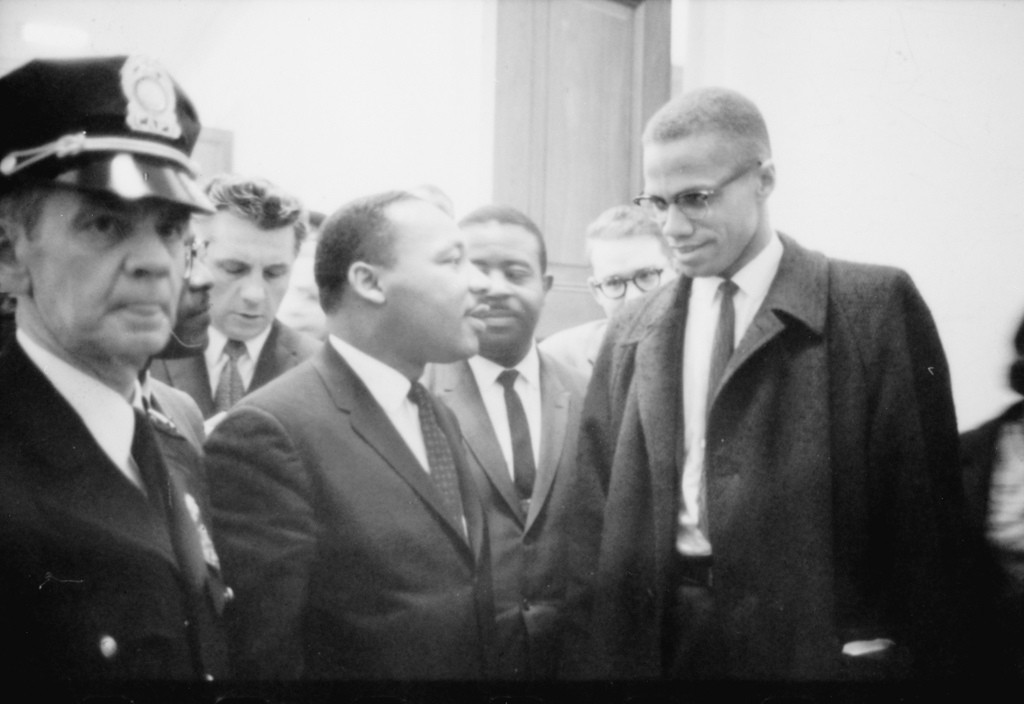

Believed to be in Public Domain From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Collections (507615074_6f06a6b08b_b.jpg) – via Flickr

Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the promised land! And so I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!!

-The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Mason Temple, Memphis, TN, 3 April 1968

The day after Martin King uttered these words, he was shot dead.

The acquittal of George Zimmerman by a jury of his peers for the shooting death of Trayvon Martin in Florida has brought to the fore a divisiveness over race and secular law that has driven us to the edge of civility, and indeed, sometimes into utter fear and madness. Even as protesters calling for justice for Trayvon Martin took to the streets in generally peaceful protests across major American cities, slanderous videos and photos were circulated online alleging that violent riots were breaking out, until some of those videos were exposed to be from Vancouver’s Stanley Cup riots in 2011 and that reports of the Oakland police car burning had exaggerated the extent of the violence in Oakland and failed to report that across the San Francisco Bay in San Francisco itself, the protest had ended peacefully.

Even so, Zimmerman’s defenders went on the defensive. They told those of us troubled by the events, the trial, and the verdict that what happened in the courtroom was the result of a fair legal process that we were arrogant to judge. They said that by bringing up racial profiling and our objections to Florida’s ‘Stand Your Ground’ laws, we were the ones being divisive. They told us that by calling Zimmerman white, we were ignorant because he is in fact part-Latino. They argued that we ignored the trial proceedings, that it was obvious that Martin had started the fight, that Martin was on top of Zimmerman when he fired, and that what we called the systematic character assassination of Trayvon Martin was a key plank in the case because his character flaws meant that he had a propensity to violence, that he had a tendency to use things like concrete as weapons, and that Zimmerman was well-justified to defend himself against this sort of hooded, thug-like teenager pummeling his head into the sidewalk. They contended that if we did not respect the jury’s verdict, then it was we who were the vigilantes advocating for mob rule.

We are divided. And yet, King prophesied that ‘we as a people will get to the Promised Land.’

Who are ‘we’?

It is tempting to write off King’s final speech by saying that ‘we’ are not being addressed by Martin King. Many of ‘us,’ for example, do not attend African American churches–what King would have called the ‘beloved community’–and even if I lay claim to my father as the only Chinese American to be ordained at Oakland’s Allen Temple Baptist Church (a pillar in beloved communities in America), the fact is that my position in an African American ‘beloved community’ may be seen by many as ambivalent. For those of ‘us’ living outside of the United States, ‘we’ may be tempted even to write this off as an American problem, to pretend smugly that what happens down there–especially in the deep American South–is nothing more than the systemic sin of racism in America with which ‘we’ share no complicity. It is tempting to say that ‘we’ are not King’s beloved community.

It is there that we are wrong. Earlier in the speech, Martin King declares:

Something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannseburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, George; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee–the cry is always the same: ‘We want to be free.’

Write that off, if you will, as an imposition of American freedom beyond its borders, even though King opposed the building of the American empire during the Vietnam War on the backs of African American soldiers sent to die by white politicians. But if there is and must be, as King says, a ‘human rights revolution…to bring the coloured peoples of the world out of their long years of poverty, their long years of hurt and neglect,’ then being neither African American nor American does not free us from complicity.

The ‘us’ for King is us. All of us.

He says that ‘we’–all of us now–‘as a people will get to the Promised Land.’ If we as a people must get to the Promised Land, then we as a people are not at present in the Promised Land. If we as a people are not yet in the Promised Land, then we as a people are still in exile. If we as a people are still in exile, then we as a people are still in the bondage of slavery. And that is what King says in this speech:

It means that we’ve got to stay together. We’ve got to stay together and maintain unity. You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite, favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh’s court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery. When the slaves get together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery. Now let us maintain unity.

If we are still slaves getting together for liberation in Pharaoh’s court, then we are still colonized. This is not American freedom from taxation without representation. This is not African American emancipation from plantation owners. This is a declaration that we–all of us–are not free because we–all of us–remain colonized.

By what are we colonized?

African American theologian James Cone asks this question in a different way: why is it that there is virtually no reflection on lynching in American theology and religious studies? For Cone, the experience of African Americans as they fear a justice system that systematically criminalizes them just for the blackness of their skin makes them Christ-figures in America. This is not because African Americans teach us to be masochists redeeming suffering for personal growth. It is because the lynching tree reveals precisely how America is constituted, especially along racial lines, revealing the things hidden from the founding of the nation: that people of colour, especially black people, are scapegoated for the cohesion of white America.

Cone’s revelation reveals in turn that King’s suggestion that the ‘we’ who are in exile are not just the African Americans who live in perpetual fear of being lynched in America. The colonized are those who have systematically been made unable to even ask the question about lynching even when it is happening before their very eyes. It is those who uncritically buy into the systems of power that perpetuate political and economic injustice against people of colour. It is those who see a mass of people protesting against the unjust conditions that strip them of their human dignity and see only troublemakers rioting in the streets.

This is why King’s references to a global human rights revolution is so significant. The lynching tree may reveal the systems that perpetuate injustice against people of colour in America as ones that exercise illegitimate colonial power, but the references beyond America reveal that this experience is not limited to America. It was also apartheid in South Africa. It is also the treatment of the First Nations in Canada. It is also the cry of the subjugated in Tahrir Square. It is also the protest of those at Occupy Central in Hong Kong. It is that when the oppressed are given voice, the structures of power propped up by the colonized themselves are revealed even as the protesters are scapegoated for wrecking the coherence of the system.

It is in this declaration that the oppressed have the rights of human dignity that King declares, ‘I just want to do God’s will. And he’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land.’ In the face of human rights protests, King declares that he knows where we the colonized are going as a people. We are leaving our exile and going to the Promised Land.

It’s the Promised Land of which James Baldwin speaks in the classic civil rights text, The Fire Next Time. I will talk another day about how reading The Fire Next Time in high school literally catapulted me into research and storytelling about Chinese churches and shaped me into a Chinglican. But here I will emphasize that Baldwin says exactly what Cone says in The Cross and the Lynching Tree, asserts precisely what Martin King declares in the ‘Mountaintop’ speech: we are colonized, and those who refuse to ask the lynching question while uncritically and unintentionally propping up structures of white privilege are to be pitied above all. Writing to his nephew about the pent-up blues of African Americans as they have been systematically taught to hate themselves by white people who don’t know that this is what they are teaching, Baldwin tells his nephew that as much as he is taught that survival in American society is premised on him integrating into white society and being accepted by white folk, this is a lie:

The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them. And I mean that very seriously. You must accept them and accept them with love. For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it…In this case, the danger, in the minds of most white Americans, is the loss of their identity. Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shining and all the stars aflame. (The Fire Next Time, p. 8-9)

Following this letter, Baldwin gives us an extensive autobiography exploring why the Promised Land must be founded on this kind of radical charity. He tells us that the church in his experience of African American communities is no better than the brothel, that many pastors are no better than pimps, asking like a pimp, ‘Who’s little boy are you?’ to which he answers, ‘Why, yours’ (p. 29). He recalls his early days as an African American Pentecostal preacher who swayed the churches with the opiate of the masses, blinding them to their colonized state and the economic injustice with which they were subjugated by white America. And yet, as he transitions into a discussion of the Nation of Islam, he realizes from encounters with Elijah Muhammad and the early Malcolm X that the solution is not to assume that all white people are ‘white devils,’ for this too perpetuates the colonized separation of whites and blacks in America premised on racial hatred.

No, Baldwin says, the revelation that the cohesion of white America is founded on the lynching of African Americans must lead us to love. This Promised Land must be love, Baldwin says, unless the fullest conclusion of racial colonization is realized in the apocalyptic bloodbath that will destroy us all in judgment; referencing Noah’s flood, Baldwin quotes the old spiritual that says of this judgment, ‘No more water, the fire next time!’

This is what is so poignant about Trayvon Martin’s mother’s tweet immediately after the ‘not guilty’ verdict was read:

Lord during my darkest hour I lean on you. You are all that I have. At the end of the day, GOD is still in in control. Thank you all for your prayers and support. I will love you forever Trayvon!!! In the name of Jesus!!!

— Sybrina Fulton (@SybrinaFulton) July 14, 2013

Sybrina Fulton is saying the same thing as Dr. King: ‘But I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the Promised Land!’

This blog is titled A Christian Thing. It recognizes that above all things, the church of Jesus Christ as the beloved community is called in its actions to herald the good news that we as a people are leaving our exile to go to the Promised Land. Seeing the face of Jesus in the lynched and the scapegoated, the beloved community calls attention to the ways in which we are all too content to be colonized and declares that the kingdom of God is near. It does so in love, not repeating the scapegoating by calling for the lynching of George Zimmerman in return, but by protesting a system that justifies lynching for the sake of social cohesion, the ‘rule of law,’ and the ‘rights of self-defence.’ Martin King has been up to the mountaintop. He has seen the Promised Land. He declared to us as a people that we will get there, and thus, to attain the love not founded on the violent myth that harmony can only be achieved by burying the murders that undergird it, we must rise as the church in protest against systemic forms of racialization that only end in death.

In that protest and in that lament, we join Martin King as he declares that he is happy tonight, he’s not worried about anything, he’s not fearing any man, because as we head toward the Promised Land, we can say with Martin King and all the saints and angels that our eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.