Great and Holy Saturday is upon us. The Great Fast has been over for a week. Even Great and Holy Week is almost over. The Lord is in the tomb. It is the time that the world is suspended by the death of God, the hiatus, the pause.

I have been reliving my catechumenate over the weeks of the Great Fast; this is, after all, what the Great Fast is for. There would be nothing special about what I have to say, except to say that every person’s reliving of a catechumenate will look different.

But my reliving of my catechumenate this year came upon me suddenly. Without much reflection on the time, I wrote some thoughts about Protestants in Vancouver and what I called their recourse to ideological ‘blackmail,’ and this launched me into a series of haphazard reflections on my awkwardness about writing about Protestants, especially because I was informed soon afterward that my comments were taken as an intervention into Protestantism. I insisted that as an Eastern Catholic, I could not possibly be intervening in the Protestant ecclesial houses; this was taken as disingenuous, and this threw me into a bit of a crisis into how it might be possible for me to write about Protestants, because this is what I still do in my professional academic life.

Because I used to be a Protestant, this series of events afforded me a tumultuous beginning to my process of reliving my catechumenate this year – even to the consideration of where I needed perhaps to be better catechized. I began writing in a frenzy, often switching between exuberant tones and thunderous critique, and my friend one day pulled me aside and informed me that he felt that my writing was becoming restless.

The crisis that ensued from this rebuke led to a new set of reflections, this time on hesychasm and what my friend and I called ‘intellectual chastity.’ I began reflecting on how hesychasm is about the body and on the work of the Holy Spirit in hesychastic practice in breaking down walls erected through the practice of the politics of identity. In the process, I confessed that I was a terrible hesychast and that I often confused the idleness of sloth with the practice of hesychastic stillness.

These were intellectual reflections – literally, reflections on the state of my intellect – and without getting into much detail, new attacks ensued. As I wrote about why I blogged in the context of my academic practice (I also have an incomplete series on why I blog) and even defended the academy, I was accused of being an intellectual for intellectuals without translating for the masses. The funny thing was that I was especially accused of this when I posted on Facebook about Protestant politics, especially the hubbub around Princeton Theological Seminary and Tim Keller.

For these people, to be an intellectual seemed to be to engage in the work of translation, of taking difficult thoughts and translating them for popular consumption. But over the course of the Great Fast, I became increasingly convinced that the praxis of being a public intellectual is to struggle publicly to be a hesychast, to have my intellect (my nous) taken into the depths of my heart to achieve a kind of stillness through which the Lord might speak to me and I could thus grasp the Holy Spirit.

This meant that I was not in fact trying to articulate the difference between me being a Protestant in the past and me being Eastern Catholic now, even though the difference between our ecclesial houses is real and should be talked about so that we can truly walk together aware of the historic gaps between our churches. But this was not a matter of identity politics. It was instead a matter of learning that theology – speaking of G-d – is not a matter of word games and discourses of identification. Hesychasm is a state beyond words, the encounter of the intellect with the truly deep, the truly profound, the truly primal.

To strive to be a hesychastic public intellectual – which means to fail publicly at it – meant that I struggled to write about the ascent of the divine ladder. My thoughts were also drawn to the service that had literally converted my body in a primal way – the Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete – and I wrote about the bodily act of performing prostrations, the impossibility of being completed by a spiritual father, and how the ‘erotic of holiness’ to be found in Holy Mary of Egypt were formative in the earliest parts of my catechumenate. As I reread the Gospels during Great Week, I also found myself beholding the face of Christ through the texts as icons. I also read with interest my friend and editor Sam Rocha skewering The Benedict Option for precisely a betrayal of such an intellectual life and its author’s absence of wit; Sam’s posts, I found, became catechetical texts for me.

My friend tells me that by probing these primal depths, I am finally starting to do theology – to speak of G-d – as Catholic. To be Catholic is to live in Christ as part of the communion of saints; this communion happens not at the level of political identification, but in the sharing of all things in the depths of existence. To be Catholic is to recognize that the sudden response of the Coptic New-Martyrs is the martyrdom that I share in the depths of being Byzantine; to be Catholic is to affirm that hesychasm is not a Byzantine thing, but a depth that is – as Holy Gregory Palamas wanted it to be – for everyone. Indeed, to be Catholic is to be able to say that even though this year I was at a conference and couldn’t attend the Byzantine services but instead attended Latin ones, and that I will be having Pascha with the Latins because a dear friend of mine is being chrismated tonight at the Easter Vigil, I am still being formed in the Kyivan Church.

This is because the whole point of autonomy for us Kyivans is not simply a matter of identity. As articulated in our catechism Christ Our Pascha, the self-understanding of what it means to be church for us in the Greek-Catholic Church of Kyiv is that we are a Pascha people. Liquidated by the cronies of the Soviet Union in 1946, our church literally rose from the dead in 1988 as our people came out of the underground in the millions, with the memory of many martyrs who had died for the union despite being vilified historically for selling out to Roman imperialism.

Of course, we are not unaware of the contested history of political machinations behind the union, and as the spiritual children of Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky and readers of Cyril Korolevsky, Archbishop Elias Zoghby, Serge Kelleher, and John Madey, we are not uncritical of the legacies of ‘uniatism’ in our practice, the propensity to prefer the traditions of the Latin church over our Byzantine heritage – a preference that the Vatican has instructed us to excise so that the fullness of our Byzantine consciousness will keep the Church fully catholic. The radical realization of our new reflection of our church is perhaps that the practice of uniatism as stated in such terms is that it is not only insufficiently Catholic; it is a perversion and betrayal of Catholicism, the trading in of one identity politics for another without any consciousness of the primal depths of communion. Catholicity is not to be found in the supremacy of one or some of the sister churches over all the others; it is to be found in our sisterhood itself. That is the point of our autonomy – that it is only in being conscious of ourselves as a self-governing church that we become conscious that our self-governance is not a law unto ourselves, but the very condition by which we can talk about our church sharing all things in common with our sister churches and walking in the hope against hope of such communion with churches not yet in the fullness of communion with us. This is only possible with a self-understanding of our church as founded by Christ Our Pascha, the Lord who gives himself to us so that we might live.

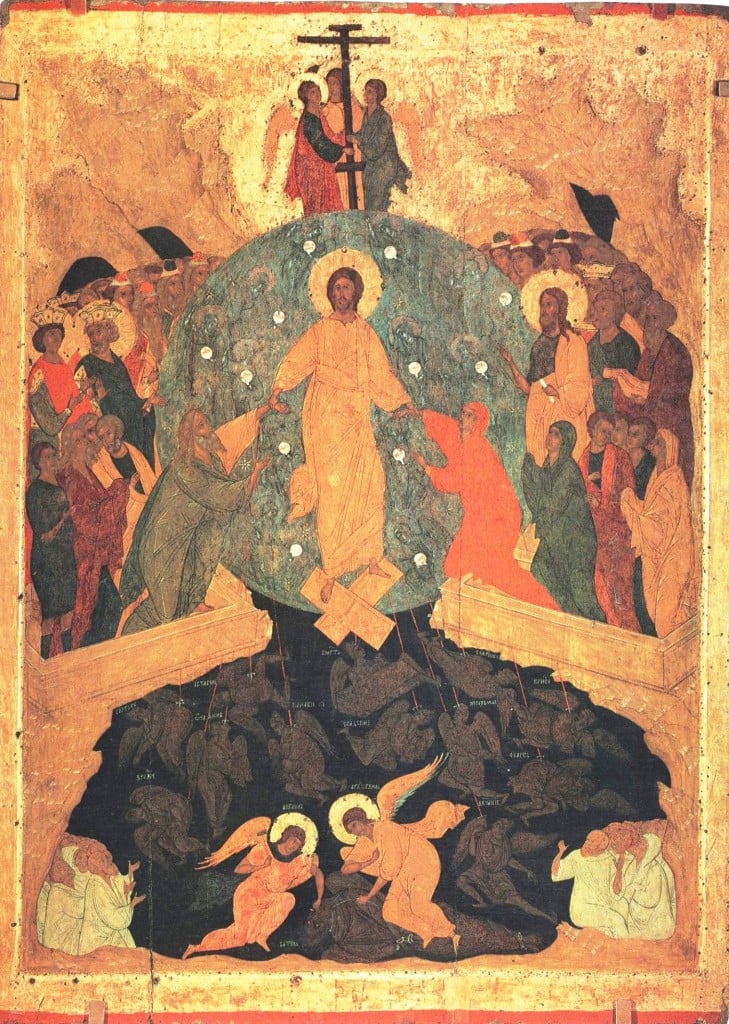

What I desire to learn more from this catechumenate relived is therefore not more information about Catholicism or Orthodoxy or Protestantism or Christianity. Instead, I want to practice speaking of G-d with such Catholic depth, to unlearn my previous practice of theological word-games so that I might be still and know that G-d is God. For Hans Urs von Balthasar, this is indeed the mystery of Holy Saturday, the death of God through which we who are joined to him descend into Hades with him, a mysterious participation that forces us to rework the ‘logic of theology’ so that the clearest expression of the sovereignty of this God is in his self-emptying.

As we enter into the feast days of Pascha, we also enter into a time of mystagogy, of being drawn deeper into the mysteries of communion, as the received catechumens become fully part of the Church, receiving the most holy Body and Blood as my friend who is joining the Latin Church tonight will. Perhaps in the days to come, then, I will be writing about reliving my mystagogy as well.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of G-d, have mercy on me, a sinner.