In my last post, I sort of let the cat out of the bag on how I’ve been translating the term 義氣, which is pronounced yi-hei in Cantonese and yiqi in Mandarin. I have been calling it the air of righteousness, with ‘righteousness’ for 義 and ‘air’ for 氣.

Yi-hei 義氣 refers to an essence of a person who is considered ‘righteous’ in a sort of Chinese martial tradition, expressed at least in South China in Cantonese street tales, opera, martial arts studios, poetry, philosophy, and even film and television now. I suppose you could say that this stuff goes for all of China too, but Cantonese is the one I know. The emphasis, I’d say, is on the street – this is a way that Cantonese people talk literally on the ground – at food stalls, barber shops, marketplaces, kitchenware vendors, and so on (and temple and church too, for that matter). The idea is that one does right by one’s family, which is constituted by the ritual oath taken by gathering around the common sacrifice. To do right by someone – usually one’s sworn sister or brother – means that one is loyal, one will do right by the other, one will not stab the other in the back or sell the other out. It’s quite serious in a way because it refers to a kind of virtue that is the essence of a person.

But there is also something comical about it too – hence, the air.

My serious-and-comic way-too-literal translation has been surprisingly well received by a number of my Cantonese friends. But one of my very righteous friends has done right by me in pointing out that the word ‘air’ can also be taken in English as ‘putting on airs,’ which is a way to describe hypocrisy – precisely the opposite of what I want to convey. Of course, what I’m trying to describe with ‘air’ is what most people who have watched the occasional kung fu movie or dabbled in ‘Eastern meditation’ (whatever that is) know as qi, the breath that is the essence of a person. Without qi, one is dead. It is sort of like pneuma in Greek or ru’ah in Hebrew – qi is the breath, which is also the spirit – and by spirit, I do not mean the faerie in English, but the breath, the air, itself.

This righteous friend of mine has encouraged me to translate 義氣 as ‘the spirit of integrity and loyalty.’ A professional exegete himself, my good brother reminds me that because there is no way to really translate 義氣 into English, a rough equivalent will do.

Certainly, my righteous friend – someone I would consider to be a sworn brother of mine in the fact that we really have each other’s backs – is more knowledgeable than me, as I grew up as a jook sing 竹升, a hollow bamboo who might look Chinese but has been so inundated with the desire to be white that I am not supposed to possess any of these Cantonese essences, much less yi-hei. But in my own defence, I must say that I got this idea for literal translations from the Chinese American classic, Louis Chu’s Eat a Bowl of Tea. It would have been hilarious enough for the novel to be simply about its main character Ben Loy recovering from a lengthy bout of erectile dysfunction (see the film too, if you’re interested). But no, Chu also goes out of his way to provide literal translations of Cantonese vulgarisms heard around New York’s Chinatown at the time that he portrays in the 1940s. Wow your mother (which is not wow your mother, but, in Chinese, 屌你老母, or f— your mother) and you dead boy 你死仔 are littered throughout the text in literal English translations. Air of righteousness is thus inspired by Chu’s spirit, though as my righteous friend reminds me, I might have to revise my bad translation soon enough.

But let’s stick with air for a second, just because I’m a stupid, stubborn jook sing. Instead of thinking of air of righteousness as ‘putting on airs,’ I might say that this air is the invisible substance that flows out of a person or an object that possesses it. We might refer, for example, to great Cantonese cooking as having wok hei 鑊氣 – the air of the wok, meaning that there is something of the substance of the wok that has so infused the cooking that it not only tastes good, but has the whole essence of the great wok (and the chef, for that matter) with it. In the martial tradition, this air, this breath, this spirit of righteousness is not only about the essence of a person, but is an invisible force that flows forth from the person to other persons who have it.

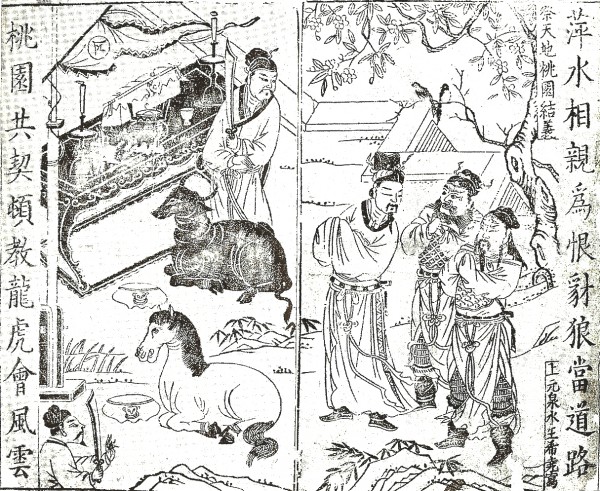

A great deal of this concept in fact comes out of the classic Outlaws of the Marsh 水滸傳, where the 108 outlaws who were portrayed as spirits that were released out of a monastery and who defied the imperial army because of reasons of integrity form a new society on Leungshan Mountain (oh, fine, if you’re Mandarin, Liangshan) that is marked by yi-hei – they even called themselves the ‘righteous bandits 義匪.’ You also see it in the other classics, like the sworn brotherhood between Low Bay 劉備, Kuan Yu關羽, and Cheung Fei 張飛 in the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 and the characters journeying to the West to get the Buddhist Scriptures (everybody seems to really like that monkey Sun Ng-hong 孫悟空). There is also Bao Ching Teen 包青天, the magistrate who was so uncorrupt that the emperor gave him three knives to execute people he found to be guilty on the spot without having to report it until later – a dog to execute commoners, a tiger to execute government officials, and a dragon to execute royals. There’s Ngawk Fei 岳飛, the great general who was loyal to the death even when executed by the emperor, there’s Wat Yuen 屈原, the official who threw himself into the river when the emperor failed to heed his advice and for which reason we throw sticky rice 糉 into the river, and there’s Mulan 木蘭 who fought for her family in the wars and demonstrated that gender is irrelevant when it comes to martial righteousness. I’m also a fan of the more contemporary exhibits of righteousness, especially Wong Fei Hung 黃飛鴻, the Hung Kuen master who was also a medical doctor (and as the literary critic Frank Chin never fails to point out, also a Muslim!), and I quite enjoy the martial stories 武俠小說 written by Jin Yong 金庸 – there’s a special place in my heart for the slow-witted, loyal-to-the-end character Kok Jing郭靖 and his way-too-smart girlfriend/later-wife Wong Yong 黃蓉 in The Legend of the Condor Heroes 射鵰英雄傳. There are far more examples than this, but these are the ones that come readily to my jook sing mind with my all-too-partial knowledge of the Cantonese tradition. I hope I didn’t get anything wrong; I am, after all, no literary scholar (I’m a social and cultural geographer, thank you very much).

One of the beauties of having a blog is being able to wrestle publicly with things with which I am uncertain. To be honest, I’m working off the fly here translating 義氣 into ‘air of righteousness,’ and my righteous brother exegete is right to suggest the alternate translation of ‘spirit of integrity and loyalty.’ I’ll probably go back and forth on this a bit, and maybe someone will suggest a third translation. Crowdsourcing is a beautiful thing, especially when you’re a jook sing like me.

But wrestle with this I must.

In many ways, the practice of everyday Cantonese life is, on the one hand, part of what brought me into Eastern Catholicism was reflecting on the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong, an event where acts of yi-hei were wrestled out on the ground in relation to the ideology of creating a stable international financial centre at all costs (which involves an abstract liberalism that is prone to betrayal in this tradition).

But also, one of the most important gifts that I received at my chrismation was from a Cantonese woman who was admittedly ambivalent at best about the Umbrella Movement – she didn’t like its chaos (whereas I revel in it). As she and her husband couldn’t stay for the dinner-and-drinks reception in the parish hall, she pulled me aside in the parking lot and gave me a set of books that she said she had owned as a child and read obsessively. It was a gift for my chrismation, she said, because she recalled that I had been reflecting on yi-hei and what it meant to grow as a person of righteousness, integrity, and loyalty as I entered the Kyivan Church, in a sense becoming even more Cantonese by becoming Catholic in a church that traces its origins to Kyivan Rus’.

The book was Outlaws of the Marsh 水滸傳, the very source for the street interpretation of 義氣 yi hei, the ‘air of righteousness,’ the ‘spirit of integrity and loyalty.’ This Cantonese essence is therefore not incidental to my being Eastern Catholic. It may even be what Holy Paul the Apostle, on the day of whose martyrdom of love he shares with St Peter I was chrismated, calls the fruit of the Spirit.