Yesterday I wrote about how I recently read Tolstoy’s ‘Kreutzer Sonata’ during this Preparation period for the Great Fast. My comments were in the context of discovering that I practiced a habit from evangelical Protestantism of seeing the world, texts I was reading, and other people as mirrors. I had written a short story titled ‘The Goldberg Variations’ without ever reading Tolstoy’s story. The piece I wrote is an unredeemable disaster; I read it a few weeks ago, and it was torture. The more I have grown in my scholarly journey and in my fledgling Eastern Catholic praxis, the more I feel that I am able to break the mirror. My sense is that Tolstoy is going to be helpful, so I hope to use this year’s Great Fast to read more of him.

I got back into Tolstoy when I began to blog on Patheos. My channel editor at the time, Sam Rocha, told me to read Tolstoy’s ‘Death of Ivan Ilyich.’ At that point, I had not read Tolstoy for many years. A lecture on Dostoevsky as the school year started for the first year of my PhD prompted me to re-read The Brothers Karamazov. But the truth is that I had not read Russian literature for many years, not since a seminar during my history undergrad scarred me with our haphazard attempt to use Russian novels by Turgenev, Dostoevsky, Nagrodskaya, and Bely as primary sources for the writing of history.

The other truth is that I had started reading Tolstoy in junior high. I had done so to impress a girl. I had overheard someone asking her to come over to hang out, and she had retorted that she’d only come if there were a bookshelf of classics. She also told me that she was reading War and Peace. I knew she was my type because she was Chinese and smart. Accordingly, I also read War and Peace.

I cannot say that I understood it. I remember getting a sense that Napoleon was invading Russia, which confused me because I thought he was a French guy. I was very bad at modern European history. But the characters of Prince Alexei, Natasha Rostova, and Pierre Bezukhov really stood out to me. I even got excited because my translation said that some pervert called Prince Anatole ‘makes love’ to Natasha. It was very exciting because my only reference point for Russian characters at the time were James Bond films, so I plugged in a few Bond girls into the character, not knowing that Audrey Hepburn plays Natasha in the movie adaptation. A few years later, I did the same thing for a bunch of Dostoevsky novels. I suppose this is what happens when one grows up in a suburban fantasyland.

The problem is that when I got to the lovemaking chapter in War and Peace (in fact, I may have flipped ahead, seeing that it was in the table of contents), all they ever did was kiss. At least that is what they did in the translation I read. That was pretty disappointing, and it wasn’t until the end when Pierre and Natasha are in bed that she grabs him and says, You’re mine, you’re mine, you’ll never get away! This scene occurs before that very boring essay Tolstoy put at the end of War and Peace about historiography. About a year later, I learned that Tolstoy had another book that was all about sex. It was called Anna Karenina, and my impression was that it would make up for all the disappointments of War and Peace. It did not. I sat there for hours and hours waiting for that Konstantin Levin guy to just ask a girl out already.

I would not say that Tolstoy did not get under my skin, even though I obviously had no idea what I was reading. Needless to say, the girl didn’t work out. Later on in grad school, I tried to convince another girl that I thought had been dating over the summer (it was one of those relationships where none of the dates were actually dates) that we could still go out because that’s like what Pierre and Natasha do in War and Peace. The ploy did not work.

All of this is to say that I have never really been a good reader of Tolstoy. I will venture to say that when I obeyed Sam and read ‘The Death of Ivan Ilyich,’ I was struck by how Ivan Ilyich’s bureaucratic life feels a little bit like how most people in my world talk about their occupations now. Lawyers, academics, journalists, and politicians say a lot even in public about having to suck up to people, attend meetings, make family life look respectable, and engage in small acts of collegial betrayal to get ahead. It was very powerful when it dawned on Ivan Ilyich that he had wasted his whole life, that the only time he was ever truly happy was when he was a child. In that moment, I thought of myself. I do not know if that is a good thing or not.

The friends who have had the unfortunate pleasure of reading my Sea Changes stories in full have mused with me about why I am such a bad reader of Tolstoy. One of these friends has read a lot of Tolstoy. She is also a former student of mine. Actually, she is Eugenia Geisel.

Eugenia tells me that what is weird about my approach to Tolstoy is that I was reading him as a kind of model minority, the smart Chinese boy who reads long books just because they are long. I agree, as this is the same reason a number of Asian Americans read Ayn Rand: you can kill someone by chucking The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged at them. The problem is that Tolstoy does not lend himself to a model minority reading. If ‘The Death of Ivan Ilyich’ is any indication, he’s against getting ahead at the risk of losing your own soul – or worse, as in ‘The Kreutzer Sonata,’ repressing your erotic inclinations until they explode and you stab somebody. It is a little funny that she picked up on the model minority bit so quickly. The truth is that I encountered the title ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’ in a Borders while looking for a copy of the Asian American historian Ronald Takaki’s tome Strangers from a Different Shore. The reason I hadn’t read that short story until recently was that I picked up the Takaki instead and gave it to my dad for his birthday. He read it on a plane and told me that he cried. I learned that Asian Americans have suffered a lot, he said.

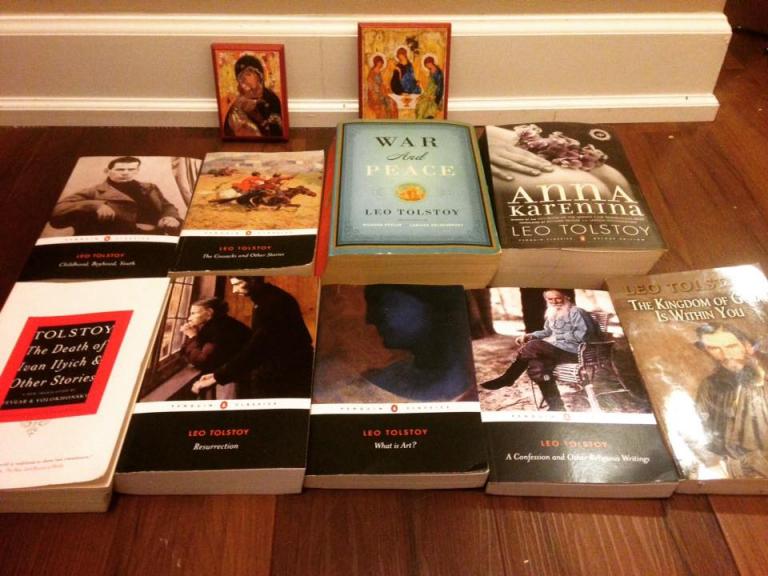

The conclusion that my friends (especially Eugenia) and I reached together is that I need to read a lot more Tolstoy over this Great Fast – and not just his fiction, but his theology too. I had been afraid that it would come to this point for some time. I have learned that Tolstoy didn’t treat his wife Sonya very well. In fact, he ended up leaving her and dying on a train ten days later. Tolstoy’s practice of marriage – and his views about women more generally – struck me as atrocious. Whatever his influence on Gandhi and King might have been, I did not want to be learning from such a man.

But as my friends and I discovered, breaking the mirror has its advantages. It turns out when I don’t need Tolstoy to be my mirror – a status symbol as the model minority, the articulator of my erotic fantasies, the guide out of a life shackled by institutional bureaucracy – then I can read him as he is. Tolstoy is not me, and I am not him. What it means to engage him is to critique him, but to criticize, I have to have read him closely.

If my memory and recent readings serve me well, I suspect what I’ll find in Tolstoy is an account of the ‘everyday supernatural.’ I don’t know if it will match my reading of the world, but I don’t think I need it to. I am, however, curious about this man who could be considered at some level as part of the Russian elite attempting to give up as much power as he could, especially in trying to relate as a person to the peasants on his land. My sense is that what I have to do is to get inside his imagination, to see the world as he is describing it. In this way, I will not only be learning from his wisdom – I will be able to criticize him too.

The discipline over the Great Fast will be to not impose what I want him to say onto Tolstoy. This will be hard because it is already a longstanding habit of mine. But I suppose what this means is that all of the psychological drama that is seared into my mind from Tolstoy’s books – the erotic repression, the depressive paralysis, the disappointments in love, the guilt over elitism, the folk phenomenology – will be given new life for me. Maybe I’ll finally understand what Konstantin Levin was all about.