Some former students of mine have joked recently that I am basically ‘Prof Yenta.’ I think they mean that I am one of those old-fashioned professor types who give out free dating and matchmaking advice to those who want it. Generally, I refrain from this practice when it comes to my current students, but somehow or another, the ones who become friends after they survive a class or two with me end up discovering this informal dimension of my teaching. I looked up what ‘yenta’ means, though, because I do not speak Yiddish, and it turns out that the meaning is much closer to ‘gossip or busybody.’ This second definition captures my condition much better, as I cannot vouch for my romantic counsel.

I have been thinking about what this nickname of mine could possibly mean for my academic praxis. It is, after all, the age of Title IX and #metoo, and the informality of these personal realms do not play well with the bureaucratic policing of campus relationships. I do not practice my ‘yenta’ ways for students in my classes, and I am married, which means that I am not in anything even bordering on the askew with any of them, but the point still stands. Sexual assault is real, and no campus knows it better than the one on which I teach, Northwestern University. The case of the Second Life philosopher Peter Ludlow continues to generate debate in the public square, especially with the publication of Laura Kipnis’s book Unwanted Advances and the furor she generated by having the audacity to defend Ludlow. Just a few days ago, the journalism professor Alec Klein was accused of predatory behaviour among his students. Needless to say, it’s a pretty sensitive time on my campus.

One of the books that I taught early on here at Northwestern was Allan Bloom’s Closing of the American Mind. I used it in my course on conservative ideologies and peoples of color because of the way that he decries ethnic studies for seeming to advance the cause of diversity while stymying it with groupthink. In my view, Bloom seems to be the last conservative that those of us in minority scholarship engaged seriously because it is so pugnaciously militant against our existence – Glenn Omatsu engages it, so does Eve Sedgwick, and recently Gary Okihiro wrote in Third World Studies that he even teaches it.

Of course, we read it in our class as an oppositional text. Quite unlike Bloom, I quite enjoy being in Asian American studies. I do not think Asian American studies is about groupthink or diversity or even identity. In fact, I am invested in studying the world and its people by militating against orientalist fantasies, which in my view prevent a scholarly exegesis of the world because it presents the lands and seas from Turkey to the Pacific Islands (and arguably the Americas too) as a mirror for the West. The task of scholarship is to break the mirror, not to read yourself into the world. Insofar as he is invested in confronting fantasy for the sake of exegesis, we were sympathetic. But when he read his own ideas about what black studies and women’s studies were into the work, we were ruthless.

The funny thing, though, is that opposition to ethnic studies is not really the point of The Closing of the American Mind; it is its entry point. The core of the book deals with what Bloom thinks university is for, and therein lies the surprise. It is, as most people rightly read it, a sappy apologetic for the Great Books written by Dead White Men. However, the reason to read them, Bloom argues, is because university is supposed to be about the cultivation of erotic desire, and this, Bloom says, is what has been forgotten as far back as the 1960s:

A significant number of students used to arrive at the university physically and spiritually virginal, expecting to lose their innocence there. Their lust was mixed into everything they thought and did. They were painfully aware that they wanted something but were not quite sure exactly what it was, what form it would take and what it all meant. The range of satisfactions intimated by their desire moved from prostitutes to Plato, and back, from the criminal to the sublime. Above all they looked for instruction. Practically everything they read in the humanities and social sciences might be a source of learning about their pain, and a path to its healing. This powerful tension, this literal lust for knowledge, was what a teacher could see in the eyes of those who flattered him by giving such evidence of their need for him. His own satisfaction was promised by having something with which to feed their hunger, an overflow to bestow on their emptiness. His joy was in hearing the ecstatic “Oh, yes!” as he dished up Shakespeare and Hegel to minister to their need. Pimp and midwife really described him well. The itch for what appeared to be only sexual intercourse was the material manifestation of the Delphic oracle’s command, which is but a reminder of the most fundamental human desire, to “know thyself.” (pp. 135-6).

Maybe Bloom is a little over the top here. His imagination of such an ideal university has also been said to be just that: idealistic. I also disagree with what he says about ‘popularized Freud…putting the seal of science on an unerotic understanding of sex’ (p. 134). But what he is saying, I think, is very relevant to our contemporary academic praxis. It means that the university is not exactly a purely rational space. It’s teeming with libido that is somehow related to the working out of knowledge.

Here, I think Freud can be read against Bloom. Bloom accuses Freud of trying to make mystery scientific: ‘Freud accepted the unconscious, and then tried to give it perfect clarity by means of science’ (p. 199). But there is something Freudian about the contemporary academy that I think Bloom would have to begrudgingly agree with: the attempt to rationalize knowledge production results in weird kinds of erotic repression, and those desires have to go somewhere. Kipnis takes it too far in her tacit defence of free love, but there is a psychological tie between the knowledge that the university has to offer and eros. Repress it, and the university becomes a giant transference machine. This dynamic has to be understood, channeled, intensified by chastity. Leave it to Aristotle to explain this problem:

Hence a young man is not a proper hearer of lectures on political science; for he is inexperienced in the actions that occur in life, but its discussions start from these and are about these; and, further, since he tends to follow his passions, his study will be vain and unprofitable, because the end aimed at is not knowledge but action. And it makes no difference whether is young in years or youthful in character; the defect does not depend on time, but on his living, and pursuing each successive object, as passion directs. For to such persons, as to the incontinent, knowledge brings no profit; but to those who desire and act in accordance with a rational principle knowledge about such matters will be of great benefit. (Nicomachean Ethics, 3).

Knowledge, in other words, requires chastity, and continence requires askesis, the training of the body. But repression is not the same thing as being chaste because hiding the passions under a rug just makes you act out. One way academics act out, for example, is that we are constantly in the habit of projecting ourselves onto our interlocutors, as if they were mirrors. It takes a kind of intellectual chastity not to do that. That, I think, should be part of my pedagogy.

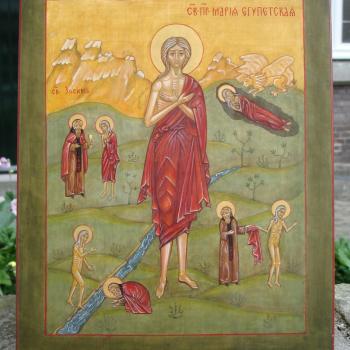

When it comes down to it, to be ‘Prof Yenta’ is to be invested in the sharing of the practice of everyday life, including in intellectual space because erotic desire is part of it. The discipline that I’ve been learning in such praxis, especially during this Preparatory time for the Great Fast, is to listen closely to what my students, especially the former ones with whom I have no formal relationship except as friend, are telling me about what they are doing. What I keep hearing is that their experience of modern love and romance, as well as on their various job markets, is to be constantly projected upon. It is like they are icons being defaced: they are looking at the person who is supposed to be loving them, but they realize quickly that that which the other loves is not them, but a projection of them. I sympathize with this; it is the transference machine at work. But my training as ‘Prof Yenta’ is not to then project my experience of the contemporary libidinal economy onto them. It is to hear what they are saying and converse with them about what they are doing in their lives. As much as my formal practices of research and teaching are important for my scholarly work, it is these everyday encounters that form in me at least the conviction about the chaste disposition I must have in order to practice good scholarship.

The paradox of being Prof Yenta is that it requires the discipline of intellectual chastity on my part. Perhaps this psychological continence is also what I am getting at with my reflections during this Preparation period on my old writing and my bad reading habits. As I am growing, I am becoming increasingly convinced that these disciplines of the intellect are the path to sainthood, the narrow way that does not fall into the psychological fallacy of repression while maintaining an opposition to the violence of rape culture – which is, as far as I have experienced the transference machine, a real thing in more ways than the physical. But I am a long way away from being able to live with such intellectual discipline. It is thus for refining my praxis as Prof Yenta that I must therefore fast.