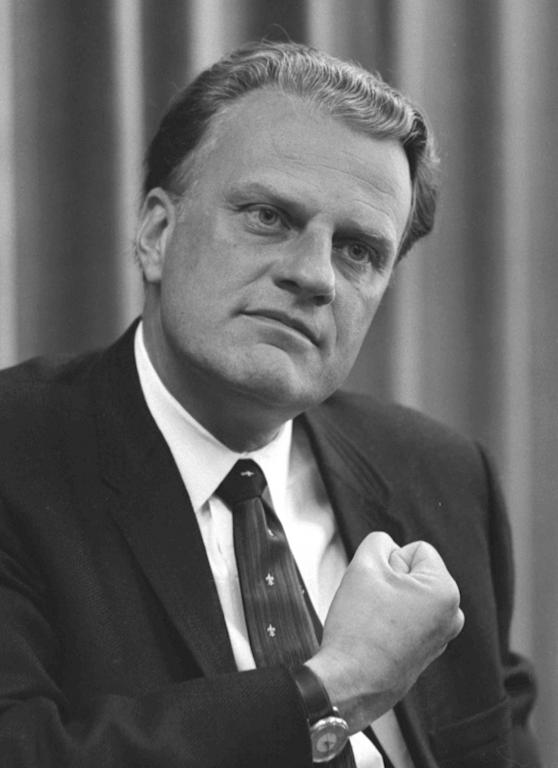

My Clean Week has been occupied by dirty politics. The preceding posts have been on neoconservatism, millennial politics and the Democratic Party, Kyivan Church geopolitics, and my education in church politics amidst the libidinal economy of the 1990s. It is only right that my next move is to discuss Billy Graham, for whom we sing ‘vichnaya pam’yat’ – ‘everlasting memory.’

I remember the first and only Billy Graham crusade that I ever went to. I was eleven, and I went with my best friend from church, who will have to be anonymized as ‘Bob.’ There are no kids in my generation called ‘Bob,’ so it is a pretty good pseudonym. ‘Bob’ was the insulting nickname we gave to our English pastor to make fun of him. We probably should have been nicer to him, and what comes around goes around, so I’m going to call my friend ‘Bob’ too.

Bob thought that the Kids’ Crusade at the Oakland Coliseum was stupid. In all fairness, it was. It was just Psalty the Singing Songbook and Charity Churchmouse prancing around the stage with a bunch of lip-syncing kids, and there didn’t seem to be any real point. Later I learned that Ernie Rettino and Debby Kerner were some of the original Maranatha people at Calvary Chapel, and that earned them some respect in my books because I once took correspondence courses from Calvary Chapel Bible College and learned all about the Jesus Movement, Lonnie Frisbee, and the genesis of the third wave charismatic movement. But having heard all ten Kids’ Praise albums since I was a little kid, I had to agree with Bob: it was kinda stupid. Also, Billy Graham wasn’t preaching. They called it a Billy Graham crusade, and the man wasn’t even going to be there. What a joke.

So the next night, Bob and I went back for the adults’ crusade. We categorized everything that wasn’t for kids the adults’ stuff. For example, at wedding banquets, we were frequently shafted into the kids’ table, where instead of the banquet food that the adults got, we got fried rice and chow mein. In time, we came to resent the kids’ menu, and we wanted to do adult things. We did not realize what the full implication of that statement were. Of course, Bob probably understood it and I was just slow. Bob went to public schools, and I attended a Christian school. Although it is not true that Christian schools inhibit libidinal curiosity, Bob was still more sexually sophisticated than me. He was always wondering out loud, for example, how much they paid Kate Winslet to take off all her clothes in Titanic. He had been talking nonstop about it that night too; either that, or he was talking about Denise Richards’s shower scene in Starship Troopers. He spoke of naked women and this band called Barenaked Ladies that he listened to but I didn’t (if I had, then I would have known that there are no women in that band). He prattled on until this lady called Kathleen Battle stepped out onto the stage. Her voice filled the auditorium. Then Bob knew that he was doomed. This was much worse than Psalty the Singing Songbook. It was classical music.

Even Andraé Crouch, who was the next act, couldn’t redeem it for Bob. Bob sat there listlessly and had probably moved on in his mind to Lara Croft’s unrealistic proportions (he was a big Tomb Raider fan). I don’t blame him. I mean, now I have an appreciation for Andraé Crouch, but being a philistine, I thought it sounded a little like Vito Corleone trying to bust a groove. Finally, George Beverly Shea came out and made it all stop. Bob looked up. Where’s Beverly? he asked.

Then, it was time for the man himself. He looked old, frail, slow. I remembered reading a biography of Billy Graham in our church library that said that he had been nicknamed the preaching windmill when he was younger. We didn’t have YouTube then, so I didn’t have the opportunity to see what that might have looked like. But this guy was no windmill; if anything, he was a windbag. And he said that he was going to preach on the offense of the cross. Boring.

I missed the whole sermon, and it was a lot to miss because it was forty-five minutes long. I thought Bob zoned out too. I wondered through the whole thing which celebrity girls he was thinking about. I didn’t watch as many movies or play as many video games as him – in fact, he was the source of much of my knowledge of the sexually secular – so I didn’t have much to flip through in my mental rolodex. But as Billy descended from his homiletic mountaintop into the valley of the buses will wait, Bob looked up at me. He saw all the people who were going down to the floor of the Oakland Coliseum, and he wanted to go too. I was surprised. Maybe the old windbag had spoken to him after all. God can melt the hardest heart.

Bob and I were disappointed. He had gone down to the floor of the Oakland Coliseum because he thought that we were actually going to meet Billy. Instead, we met a middle-aged guy whose name was actually Bob. He asked us if we wanted to ask Jesus into our hearts. My dad had come down with us, and he said that he was a pastor, so he was good. I said that I had done so already, but I spied a line item on the tract that the real Bob was holding saying that I could rededicate my life to Christ. I had already rededicated my life to Christ at a camp meeting during Outdoor Education for my Christian school, but the beautiful thing about ‘rededication’ is that, unlike asking Jesus into your heart, you can do it as many times as you want and not have to tell anyone that you felt unassured of your salvation. Later on, I learned that when Anglicans say that confirmation is rededicating your life to Christ too, it’s all lies. If you rededicate your life with them, you become Anglican.

My friend Bob wanted the full package, though. That meant that he had to kneel down and tell God that he was a sinner. He had to dedicate his life (as opposed to rededicating it like me) to the Lord, and he told Jesus that he wanted him in his heart. Then the guy who prayed with him, the real Bob, gave us his number and said that he’d be following up with us soon. He did, six months later. I told him I was fine. I wonder what Bob told him.

I soon learned that Billy Graham was a man of integrity, and that’s why we had gone to the Oakland Coliseum to see him. If you think about who everyone in America trusts, it was said to me, it’s Billy Graham. Among his qualities, it was said that he had the trustworthy look. My parents – and for that matter, people at my church – liked that look. I mentioned yesterday that when I was a kid, my parents had been admirers of lots of presidents who also looked like they had integrity, especially Reagan and Bush. But they revered Nixon. They liked him a lot. They thought that Nixon looked like he was really a man who could be trusted.

I didn’t know who Nixon was, so I just went along with it until I read the church library biography of Billy Graham. Poetically, it sat next to a biography of a guy called Charles Colson; the front cover had a picture of this dude who looked like a bulldog behind bars. I never bothered to skim more than the first part of the Colson biography, so it was from the church library biography of Billy Graham that I learned something about Billy’s relationship with Nixon. Nixon, the book said, had somehow been mixed up in a burglary. I didn’t know that presidents burgled other people’s houses, but I got the impression that Nixon somehow had to resign the presidency because he was a burglar, and that had stressed Billy Graham out. Of course, that church library biography was written at a third grade reading level, so great scholar that I was, I decided to consult the book for adults: Just As I Am. I knew that it was an adult book because it was 800 pages long, right up there with The Lord of the Rings, War and Peace, and Atlas Shrugged.

Using the impeccable research skills that I had mostly acquired from the Christian school, I scoured the index for Richard Nixon. After a bazillion pages popped up, I almost gave up. Then I discovered that Billy had arranged his autobiography around his relationship with the presidents. That meant that there was a whole chapter on Nixon, and the index had given me every single page of that chapter. I read it and didn’t care for much of it until I found a scene that corroborated what I had read in the church library biography. Billy recounts sitting behind Nixon in a theater. I thought this was strange because I didn’t know that presidents, much less Billy, watched movies. Billy was more like Bob than I thought. When Nixon gets up, he looks at Billy and looks like he’s going to be sick. Billy says something about praying for him, and soon Nixon resigns.

I learned from reading around Just As I Am that the whole affair was simply referred to as ‘Watergate.’ There was a big water tower off I-80 near Stockton, and that’s what I thought a Watergate was. That confounded me further because it made no sense that Nixon would want to burgle a water tower. After all, this was real life, not The Hobbit. Utterly confused, I read that chapter of the autobiography obsessively until I managed to piece together some of the details. It turns out Nixon wasn’t the burglar; it was five other guys. But he knew about it, and so did that Chuck Colson guy, although I was not sure how he got mixed up in all of this, as his only relation to Billy as far I was concerned was the proximity of his biography to Billy’s in the church library. Billy never did manage to clarify why they wanted to rob a water tower.

In any case, both Nixon and Colson were guilty of knowing about the Watergate burglaries, which still made no sense to me. Later on, I learned in AP US History that those guys were hired by a group called CREEP, the Committee to Re-Elect the President. That sounded creepy, and I brought it up the next year to my AP Government teacher. She asked me if I’d seen All The Presidents’ Men. I learned to my great embarrassment while watching Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman that if I had just watched this movie and read the book it was based on, I wouldn’t have had to work so hard to read Billy Graham’s autobiography in my quest to figure out what a Watergate was and why Nixon and Colson were guilty. But I suppose you don’t really know things when you grow up Chinese evangelical and actually try to be one, unlike Bob and his Titanic fantasies.

Billy Graham’s unwitting influence on me extended into my college years – and arguably into grad school too. I had a romance with postmodernism in my early undergraduate years, and so did a group of evangelicals called ‘the emerging church.’ There was a guy called Mark Driscoll who was part of that, and I found his book The Radical Reformission at a greatly reduced price in a tub of sales books at a Christian mall outlet. Driscoll writes about a number of his influences in relating ‘the Gospel’ to ‘the culture,’ which is where the postmodernism comes in. Of course, this is why I’m not as easily fooled by Jordan Peterson as everyone else; he’s not the first popular speaker I’ve encountered who has no idea what he’s talking about when he uses the word ‘postmodernism.’

In The Radical Reformission, Driscoll tells a story about randomly meeting Billy Graham in a restaurant that they happened to be in together at the same time. He walked over, introduced himself, and Billy placed his hand on his head and prayed over him. Because of this, Driscoll claimed the mantle of Billy Graham over his ministry.

Most people know Driscoll for the misogyny, and I don’t blame them. Those of us who have followed the Mars Hill saga know that what brought down the house of cards was actually financial misappropriation in an institutional structure that piled legal fiction on top of legal fiction. But in the early 2000s, the contemporary lines between evangelicals weren’t as well drawn out as they are now. The term ‘New Calvinist’ wasn’t coined until 2006 in the pages of Christianity Today. As far as I was concerned, Driscoll was just trying to figure out how to preach to a culture that he claimed was ‘postmodern,’ and he had an eclectic mix of influences. There was, of course, John Piper, but Driscoll also liked Chris Rock’s comedy style. He cited Graham too. He said that whenever Billy pokes his finger into the television screen and tells his impersonal audience to accept Jesus into their lives, he’d cry. In so doing, Driscoll gives a positive spin to the immortal words of Neil Postman:

Not long ago, I saw Billy Graham join with Shecky Green, Red Buttons, Dionne Warwick, Milton Berle, and other theologians in a tribute to George Burns, who was celebrating himself for surviving eighty years in show business. The Reverent Graham exchanged one-liners with Burns about making preparations for Eternity. Although the Bible makes no mention of it, the Reverend Graham assured the audience that God loves those who make people laugh. It was an honest mistake. He merely mistook NBC for God. (Amusing Ourselves to Death, p. 5).

I don’t think Postman was one of Billy’s fans. You can’t win them all.

Because of Driscoll, I started listening to a number of preaching podcasts and reading old sermons. I was a history major, and I wrote a number of my papers on historical sermons by Jonathan Edwards and Martin Luther King, Jr. I also podcasted a range of sermons, but my proudest achievement is to have listened to every single sermon in John Piper’s series on Romans. Of course, I listened to a lot of Driscoll too. But what I really tried to get access to were Billy’s sermons. That’s when I finally understood the power of his preaching. Driscoll was right. Billy’s strength was his ability to take from popular culture and spin it into the gospel. He took signs from showbiz in New York and spun it into the message of eternal salvation. He stole King’s lines about having a dream and dreamt at Lausanne of the gospel reaching the ends of the earth. He spoke of the offense of the cross as a stumbling block to a culture based on glory and wisdom.

In other words, Billy’s power lay in his rhetoric. There’s a story of two anthropologists who go to a Billy Graham crusade to conduct an ethnography of it, only to feel convicted by Billy and come down in tears during the altar call. What went around then came around: Driscoll in turn appropriated these Billy Graham tropes and made them his own. In Confessions of a Reformission Rev, for example, he tells the story of a fire marshal coming to shut down Mars Hill for exceeding its seating capacity, only to be converted by his preaching.

I have heard from reliable sources that my doctoral supervisor – the geographer – was converted at a Billy Graham crusade. I’ve never talked to him about it, but I don’t doubt it. Over the years, he and I have debated exactly how critical of evangelicals I should be in my academic work. The evangelicals I write about, of course, are in one way or another related to Billy. One of the most prominent Chinese American evangelists, the Rev Thomas Wang, was even a collaborator with Billy. Wang is similar to Billy in two uncanny ways: he was at Lausanne in a prominent leadership position, and he also just died.

Wang’s collaboration with Billy Graham has made the writing of the paper I’ve been trying to write forever called ‘America Return to God’ interesting. It’s an attempt to understand Wang’s crusade against same-sex marriage in the later part of his career on his own terms. Some people would say that he was just standing up for a good old orthodox understanding of Christianity, but his argument was basically that gay rights are a grand communist plot against America that began with taking prayer out of schools. That is not an argument from any kind of Christian tradition; it is literally called making stuff up. You could say that this delusion comes from an ‘evangelical worldview’ that has to be respected on its own terms, but I thought that the mothers and fathers of modern evangelicalism believed that they were defenders of propositional truth in a world of nihilism. Any research into the history of how same-sex marriage even became a thing (not to mention that it is a socially conservative experiment, as far as Andrew Sullivan and his critics are concerned) will demonstrate that Wang’s proposition about the big communist plot is patently false. Coming to terms with this conclusion, however, has been a bit of an emotional roller coaster for me because there’s a religiously romantic part of me that really likes seeing Wang (and Graham) as a hero of the faith. Writing this article has thus been difficult, to say the least. Every attempt I have made to wrestle that essay to the ground has failed for years.

But every time I make an attempt to write about Thomas Wang again, I come across the towering figure of Billy Graham. Researching Graham for that poor paper has in turn cast doubt for me on the popular portrayal of Billy as an evangelical who had some cool liberal views about the environment and nuclear weapons and collaborated with all kinds of Christians who weren’t his brand of Protestantism to fight social anomie and philosophical nihilism. Contrary to those who seek to differentiate Billy from his Trump-supporting son Franklin, Billy was never distant from the Christian Right; in many ways, he was one of its ideological founders. I learned, for example, that when the school prayer case Abington School District v. Schempp happened in 1963, Billy gave an interview to the New York Times decrying how taking prayer out of schools would destroy the moral fabric of America. Christian conservatives are not making stuff up when they blame everything from school shootings to same-sex marriage on prayer in schools. They’re quoting Billy.

Still, Billy’s legacy lives on in my life, even as I have entered the Kyivan Church. In light of his repose three days ago, many in my church and our sister Eastern Catholic churches have been taking to social media to laud him as a great man of God. I suppose he was, but some of us in the Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group have been musing about the strange curiosity of his need to act like the first to proclaim the Gospel in post-Soviet Ukraine when our church had been doing it in the underground for almost fifty years. Still, my spiritual father sometimes quips whenever we organize social justice events that if we want to be effective in gaining a critical mass, we need to do ‘the Billy thing.’ He remembers when Billy came through one of the cities where he was a priest at some point in his career. The real achievement wrought by that event was that the various Protestant, Catholic, and even Orthodox groups got together and learned about evangelism. In some ways, Billy simply became their front guy, an excuse for them to organize something ecumenical. I like that. Like my experience with Bob, I am starting to get the feeling that the Billy Graham Crusades seldom had anything to do with Billy. From most of what I hear, they tended to be excuses for people to do their own thing.

Billy Graham died three days ago, and I have sung a Вічная Пам’ять (vichnaya pam’yat, ‘eternal memory’) for him already. He might even deserve a panakhyda for the sheer fact that he was the one who taught me about Watergate. He will remain in my daily prayers for the dead for the next forty days or so. Working through my reflections on his influence on my life, scholarship, and even current ecclesial status has been tremendously clarifying. Maybe I’ll finally get those essays on Chinese evangelical conservative ideology done after all. The distance that Eastern Catholicism has afforded me from evangelicalism may turn out to be the extra push I need to write. Perhaps I’ll ask Billy to pray for my writing. Now that he stands before the face of G-d, he probably now knows that he can, and since he is also more than aware that the only test of his work will be the fire of eternity, surely he will think that my critical view of his career is but small potatoes.