Lord, I am here. Lord, I am yours.

‘A human being today feels the need to belong to a community that holds the same values regarding family, culture, nation, language, profession, vocation.’ How predictable, someone might say upon realizing that these are the meditations of the Kyivan Church on the Sunday of the Holy Fathers, this third of our Mission Days. Is this not exactly the sentiment that drove the protests on the Maidan, for which Ukrainians have been roundly framed as regressive for wanting to be part of the European Union and NATO, not to mention the ways they’ve also been gaslit as neofascists? Is this not a statement in favor of the ethnonationalism that gets in the way of global solidarity? Is this not symptomatic of a kind of right-wing ideology creeping into our churches?

I don’t think so. For one, such responses betray a lack of knowledge about the complexities of Ukrainian street politics at the level of the everyday. Indeed, the other day, I saw a noted Ukrainian Orthodox theologian post on his social media that perhaps what is needed in the analysis of Ukraine – for him, the case of autocephaly for the Ukrainian Orthodox churches – is a grounded, sociological analysis. Enough with the parsing of official statements, he said. There are people who live in Ukraine, who walk its streets, who create meaning in their everyday lives that do not match up with official ideologies. As my friend Julian Hayda is fond of saying, such quotidian practices are indicative of a broadly anti-colonial politics, a refusal to be dictated to by colonizing ideologies. Indeed, this was the point of Maidan as a Revolution of Dignity: it was that the people of Ukraine were not going to be taken for fools by their political masters and demanded a future that they themselves would create.

But what is the basis of such a politics? Is it really the ideological values with which the Kyivan Church opens today’s meditations? Again, the answer is no. Here, the Kyivan Church is not making a normative statement about the human desire for connection; she is diagnosing the condition of humanity in a modern situation. We feel the need to base our personal bonds of solidarity with each other on the basis of shared values, she says. However, this feeling is also inadequate. At one level, the technologies that we have built in modernity to facilitate human communication do not truly suffice for authentic connectivity: ‘And in spite of all the technological possibilities for social communication, we all still seek authentic personal contact with another person.’ But at another level, the second sentence there draws out the inadequacy of connecting with another person solely as a set of ideas. ‘The most precious moment in life,’ she continues, ‘is when one person says to another: “I am yours” or “you are mine.” In that moment, a person knows that he or she “belongs” to someone and is part of a special relationship.’

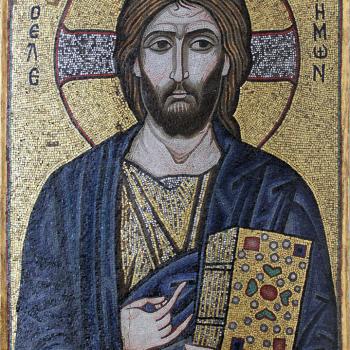

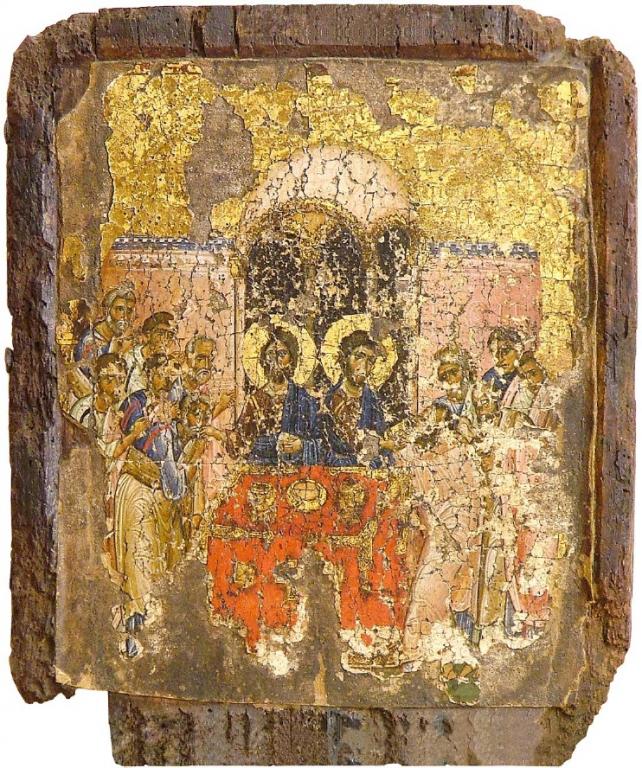

Connection, in other words, is not ideological. It is personal, and this personalism is based on our Christian theology: ‘When we think about God, we come to understand that special relationship that exists between the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit because such a relationship has parallels in our human experience.’ Indeed, there is more than an analogy; the Church quotes the kondak for the Ascension in which we sing that ‘we are invited to share in God’s life: “in no way distant, but remaining inseparable, You cried to those who love You: I am with You and there in none against You.”‘ The complete interconnectedness of the persons of the Triune Godhead in ‘will, reason, life’ comes to us in the Eucharist. Here, the Church cites her beloved Patriarch Josyf (Slypyj) of blessed memory as he reminds us that while ‘poets leave behind their works in remembrance, sculptors and artists leave their statues or paintings in order that they may be remembered…the greatest living remembrance has been left for us by Jesus Christ: He gave us His Body, His Blood, so that we might remember – “do this…” – that this Body and spilled Blood is passed on for the forgiveness of sins.’ The action points that the Church prescribes for today, then, are to pray the Prayers of Thanksgiving after Holy Communion in our prayerbooks as a ‘family practice,’ to think of the persons in our temples who are bonded together in sharing the Most Holy Eucharist, and to ‘make every effort so that before unbelievers our Christian demeanor be our sermon about a God, who wishes to embrace all humanity unto himself.’ Ite, missa est, the Latins say when they ended the mass; it means that they are sent out into the world on a mission. Ours in the Divine Liturgy is even more pointed: ‘let us go forth in peace,’ the priest says, and the people respond, In the name of the Lord!

The satisfaction of our desire for human connection is in sharing the life of God. ‘And this is eternal life,’ our Lord prays in the Gospel we read today at liturgy (John 17.1-11), ‘that they know you the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.’ This knowledge is personal: the Father is in the Son, the Son is in the Father, and the Son is among his people and is glorified in us by having us brought into the intimacy of the Father’s bosom by the Son who was begotten of him. We eat the Son’s body and drink his blood; that this is the deepest human connection is a statement of judgment against the secularization of this communion into ideology. There is no flesh and no blood in an ideology. Values are not what we long for. As political theorists as diverse as Benedict Anderson, Bill Cavanaugh, and Gil Anidjar have shown, the secularization of the connectivity of the Eucharist into the political borders of the modern nation-state and the networks of global capitalism have been unsatisfying counterfeits, sometimes leading even to genocide. We in the Kyivan Church here in Chicago agree: last night, we had a concert in Millennium Park commemorating the eighty-fifth anniversary of the Holodomor, the Ukrainian genocide famine ostensibly based on class warfare but really about a kind of Stalinist retrogressive nationalism. At that concert, the speakers condemned genocide in all its forms, including against indigenous peoples in the United States and against Palestinians by the State of Israel. As the theologian Henri de Lubac suggests in Corpus Mysticum, the turning of the Eucharist into a kind of ideology of connection can turn into justifications for the state to render what it considers threats to the body politic killable. So too, perhaps the strongest statements that Marx makes in the first volume of Capital are against the ‘transubstantiation’ of objects into the fetishized magic of commodities that circulate in global markets as capital and necessitate global colonization, the turning of persons themselves into cogs in a market machine. The secularization of the Eucharist has bred modern tragedy. We are not made for such oppression.

The Church invites her people thus to rediscover the source of personal connection. It is not in ideology. It is instead in the offering of Jesus Christ for him to quite literally be in us, that we may be caught up in the life of the Triune God. Having partaken of the Eucharist, we are sent out from the Divine Liturgy on this anti-colonial mission, to expose the oppression wrought in the world by the secularization of Christian communion and to invite it to return to the God who forgives and draws us into the fullness of his life.

Today is the third of ten Mission Days in the Kyivan Church from Ascension to Pentecost.