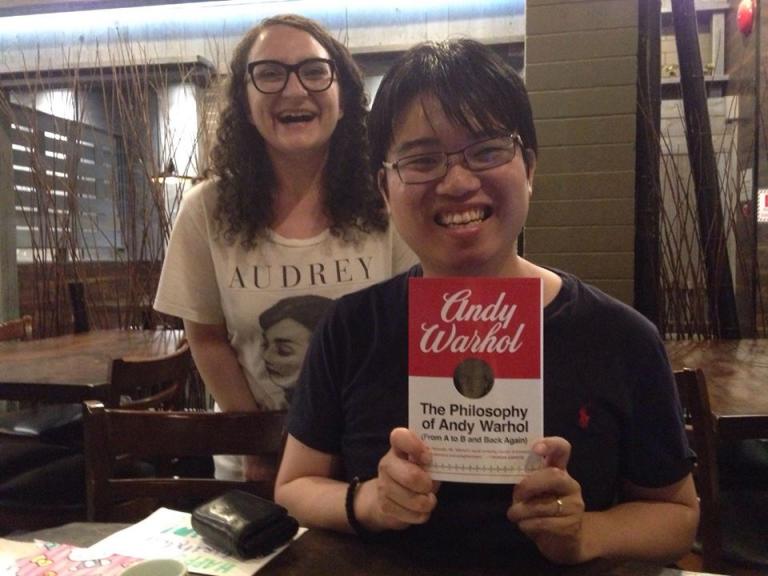

Yesterday, we dropped off our dear sister Eugenia Geisel at the train, fresh from a weekend in which she truly flattered us in Richmond by calling it her vacation, true flattery because it suggests that we are actually relaxing to be around. She, of course, came up with a message in the form of a birthday gift. Wrapped in Hello Kitty wrapping paper – her trademark since taking that trainwreck of a class with me at the University of Washington titled ‘trans-Pacific Christianities‘ – was a book, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. She told me that it’d be helpful for the project on the psychoanalysis of publics I’ve been working on. We had just finished a sushi meal to celebrate her coming into town, and my wife motioned for Eugenia, gloriously garbed in an Audrey Hepburn t-shirt, to stand behind me for a picture. I posted the photo on Facebook a few hours later, and Julian Hayda – another member of ‘the growing number’ of our ‘much ballyhooed‘ Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group – commented back immediately that Warhol was Byzantine Catholic.

To be honest, I have long been suspicious of the easy claim for Andy Warhol to be one of us, so to speak, in Eastern Catholicism. I think I first read about Warhol as Eastern Catholic somewhere on the Catholic blogosphere during my catechumenate. There was something about him sitting in the back row of daily mass to avoid being seen ‘crossing himself the wrong way’ or something like that because he was Byzantine. I took this information to my spiritual father, and he confirmed it: Warhol’s name was originally Warhola, a typical Ruthenian name. Sure enough, as I searched more, I learned that he had been raised in the Ruthenian Church and is buried in a Byzantine Catholic cemetery.

But I have been long suspicious of this evangeliCatholic attempt to rehabilitate Warhol, especially as someone who had to be a celibate Catholic because he was widely known to be gay. It sounded a bit like the evangelical hagiographies where ‘godly’ women and men we looked up to as missionaries, evangelists, pastors, and role-models for courtship and marriage all had to be chaste and would only get to have sex in a cookie-cutter way: we declared our intentions to each other, we honored our parents by asking for their blessing, we worked out our problems with a premarital counselor, we got married in a God-honoring ceremony, and somehow all of that didn’t manage to kill the mood because we now bang every night. In order for Warhol’s explicitly sexual meditations on popular culture to be somehow acceptable for Catholic consumption, he has to be presented as secretly asexual.

On top of it being very hard to align this imaginary narrative with the messiness of Warhol’s category-defying life, another problem with this fantasy is that asexuality is not the same thing as chastity. Chastity calls for the integration of body, psyche, and spirit through personal training in mastering the passions so that one can channel erotic energy in all of its intensity in ways that build up instead of destroy the world which we inhabit together. Ideological stories speculating about Warhol’s asexuality feel suspect to me because they run in the opposite direction. The imposition of a tidy narrative on top of a kaleidoscopic mess actually runs toward alienation and disintegration. Colonial order, which is what imposing a story about how something must have been instead of how it actually was is, is actually not that orderly. It just sweeps inconvenience under the rug, presenting to the world the veneer of neatness without actually integrating it. Such colonizing impulses are a betrayal of everything that Warhol stood for, especially the integration of pop culture fragments and shards of the libidinal economy as themselves the ingredients of artistic work. Indeed, the only integration I see here is the one between evangelicalism and Catholicism into the unexpectedly ‘uniate’ form of evangeliCatholicism, where the sexual nervousness of the former takes on weird overtones with a hagiographic culture of writing, often by colonizing it.

The more convincing story is that Warhol was, as some of us converts like to joke, ‘saved by his DNA.’ He was born into the Ruthenian Church. He was raised in it. The imaginary never left him. He probably did attend daily mass, and I don’t care enough about his sex life to find out whether he only made a film depicting a blowjob without ever having one himself or actually had that and more throughout his illustrious career. Eventually, he died because his gallbladder surgery went badly, and he was buried in a Byzantine Catholic cemetery because that is what he was ethnically, canonically, ecclesially.

That said, I’ve never really been content to consider Andy Warhol’s Eastern Catholicism just be nominal and incidental either. Part of it may be the way that I’ve encountered his work. The funny thing is that when Eugenia was up in Richmond for my chrismation two years ago, I also picked her up from the train station. That time, it was she who was reading The Philosophy of Andy Warhol and waved it loudly in my face as she met me. I was rushing to finish my assigned reading for my catechumenate – the day before being received into the Kyivan Church – and the last thing on the menu was Melinda Selmys’s Sexual Authenticity, a book on chastity by meditating on how John Paul II’s theology of the body actually translates into everyday life.

The truth is that I had been reading Selmys so slowly because it felt on the one hand like she was saying something different from the average evangelical and evangeliCatholic, but a lot of it also felt on the other hand like more of the same in terms of its rhetoric, based mostly on anecdotes and analogies, to the popular sexual apologetics to which I had been previously accustomed. The other confession I must make is that, for all of my seeming nonchalance about sexuality on the blog, one of the first things that drew me to Catholicism was the Theology of the Body. This is quite the admission because I don’t want to be just another evangelical convert who found Catholic teaching on the erotic language of the body more compelling than the ‘this is what the Bible says’ propositionalism of evangelicalism. In fact, I was convinced at one point that it would help the Anglican Communion get through their impasse on sexuality and was persuaded that Rowan Williams’s essay ‘The Body’s Grace‘ had similar impulses. Alas, I am not that cool. I am much more typical of an evangelical convert than I care to admit, obsession with sex included.

The real irony, in other words, is that while Eugenia was first reading The Philosophy of Andy Warhol en route to my chrismation, I was probably much closer at the time to the evangeliCatholics that I’m now complaining about trying to rehabilitate Andy Warhol and therefore finding themselves caught between hagiographic ideology and the messiness of reality. But two years later, the scene has repeated almost exactly – we pick up Eugenia from the train station, we drive her to food in Richmond, she is still waving The Philosophy of Andy Warhol in my face. Yet this time, I am much less confused, or at least less consumed by the obsessions that precipitated my conversion. It took a few minutes for me to clue into who Andy Warhol was the first time Eugenia waved his book in my face, whereas my wife – whose penchant for usually managing to view every work of art in each gallery we’ve visited with focused attention reveals that her aesthetic sensibilities are much more developed than mine – instantly recognized him as the soup can guy. This time, I was as quick as my wife in recognizing the book and its author. Surely, this is evidence of maturation, but what’s even more amusing, I think, is that Selmys, the author I was reading at the time, has now become a colleague here on Patheos Catholic and is also evolving as she ushers us now into the mess of her current reflections on Humanae Vitae. Catholic maturity, Selmys and I both seem to be finding, has little to do with juridical conformity with a magisterial superego. Thinking with the church instead requires intellectual integration with the stillness of the heart.

Two years after my chrismation, I’ve begun describing my time in Eastern Catholicism as one of reclamation. I am reclaiming much of what I’d consigned to the ocean of my unconsciousness in my flirtation with a number of permutations of white colonial evangelicalisms, Protestant and Catholic, from the New Calvinism to Radical Orthodoxy. What seems to be resurfacing are my commitments to psychoanalysis and critical engagements with transference in everyday life, a Cantonese ethical orientation to institutional politics, and the feminist and womanist convictions I developed while learning liberation theology in what Eugenia has noted to be the erotic personalist space of Catholic school. I’ve even gotten back the pop culture of the nineties that I had rejected in my youth when I’d tried to be a model minority conservative, the kind of Chinese guy whose knowledge of the elite and esoteric contributed to a delusion that I was better than everyone else. As these intellectual fragments have resurfaced, I’ve attempted to write through them, some of it on the blog, though the bulk of it is actually in personal journals and academic writing coming through the pipeline. The process has been from fragmentation to integration, actively working through the publics that have addressed me as if cooking a feast or creating a work of art.

Is this not the Warholian impulse? Did not Warhol’s genius lay in his making art out of what Michel de Certeau SJ observed was the way that ordinary folks poach from the institutional grids that impinge on their everyday lives and rework it for their own mythological imaginaries of the world as if they were cooking a meal with actions like cutting out and turning over? Did not Warhol seize on the mediated publics of his day and show the world how his mind processed them? Are not these acts of integration closer to the practices of chastity taught by the Catholic Church than the repression more commonly associated with the term?

If I were to lay claim to Andy Warhol as a kind of Eastern Catholic figure, these would be the avenues down which I might travel. These lines of thought have less to do with a case for his sainthood – and also take me far from the silly temptation to somehow see Warhol’s art as iconographic – and have much more congruence with the mystagogical experience I’ve been having in this church. The path that Warhol takes to chaste integration is far from the evangeliCatholic impulses that precipitated my conversion. I think Eugenia has been watching this develop in my thought; indeed, she said to me as she gave me the book that it would ‘help with my psychoanalysis project.’ I said back to her that my thinking had in fact been brought to the work of Andy Warhol through our conversations about popular culture. Through our discussions, I had in fact found a place where Lady Gaga says in an interview with CNN about her early work, well before her explicit homage to Warhol in her third album Artpop, ‘That’s the most Warholian thing about what I do… I embrace pop culture. The very thing that everybody says is poisonous and ostentatious and shallow, it’s like my chemistry book… and I make what I believe to be art out of it.’ Awwwwwwww yeeeaahhhhh, Eugenia replied. It’s what she says when she has a big mood, and she deserved it, having touched on the raw nerve that my experience of mystagogy and my psychoanalytical integration of my ascetic training in chastity with my intellectual life had unexpectedly developed. I promise now to read the book.