If there is anything I’ve learned since becoming Eastern Catholic, it is that the Holy Spirit seems to care deeply about my intellectual life. As I’ve continued to struggle in crafting a way forward as a geographer freshly re-committed to the postsecular between religious studies and Asian American studies, I’ve stumbled on a way of framing research in the academy that sounds like a fad, but has such deep moral commitments that I have been nervous about writing it off. The term is settler colonialism, and I have been discerning if the future of my scholarly agenda might have something to do with examining it as an extension of my work on publics.

The anthropologist Patrick Wolfe first used the term settler colonialism to talk about a particular kind of colonization that was left out by previous postcolonial scholars, such as Frantz Fanon. In the tradition of what Gary Okihiro calls Third World studies, colonialism refers to the process by which European capitalists, in league with their imperial nation-states and with allies in educators and missionaries, would set up settlements in places where there were already people and exploit the local people and their lands to grow cash crops or mine their resources, turning those areas into sources for commodities. This process was traumatizing enough – it’s what motivated Fanon and others to write about liberation from this arrangement, as well as the psychic damage it had done to the people being colonized – but for Wolfe, it didn’t spell out the whole picture. There is another kind of colonialism that precedes this kind of exploitation, Wolfe says, and it’s the kind where you clear out the local people either by exterminating or displacing them, settle their lands, and re-settle the area with workers who might do your capitalist bidding. This genocidal mode of colonization is called settler colonialism.

Settler colonialism has been debated for a while in the academy because it both is and is not useful for describing the experiences of indigenous peoples, folks who are original to lands that were then colonized by others. On the one hand, it is very useful, because it can describe all manner of violence done to eliminate indigenous presences on the land, including through the psychic and biological terror of attempting to educate ‘Indianness’ out of the natives in the North American nation-states through residential schools. It also has tremendous utility in describing the ways that capitalist operations seek to expand onto native territory and displace the people there so that resources can be mined, pipelines can be built, resorts can be erected, and so on and so forth. It can also be used to explain why it is that settlers feel the need to ‘play Indian,’ as the scholar Philip Deloria puts it, such that the cultures of indigenous peoples are appropriated while their bodies are killed off.

But on the other hand, there is an ahistorical quality to the concept, in the sense that it was not always the case that indigenous peoples were always eliminated by European settlers, but were rather engaged in all kinds of interactions from trade to warfare. Those who aren’t careful might also find themselves in the awkward position of always seeing every indigenous person and institution as good because they are always victims and every European from anywhere in Europe as bad because they are settlers. The truth is a lot more mixed: there are liberation traditions that come from Europe (one thinks all the way back, for example, to the work of Bartolomé de las Casas OP, as well as the Jesuits I describe below), as well as corruption to be found in native institutions, so much so that some posit a difference between governing councils and the actions of the people (and that is already simplified and simplistic).

I became interested in the concept of settler colonialism almost by accident. I teach Asian American studies at Northwestern University, and one of my core courses is Asian American history, where I present a view of the field best worked out by the historian Gary Okihiro that emphasizes the thesis that ‘Asians did not come to America, but America went to Asia.’ In making this case, I have to describe what Okihiro calls the social formation – the network of institutions – by which the Americas were not only colonized, but also historically mistaken for Asia by explorers and traffickers like Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci. This account calls, then, not only for a history of Asian migrations to the United States, but also how the logic of settler colonialism governed the actions of settlers both on the American continent with relation to indigenous peoples there, but also the Pacific Islands. Famously, the United States’ war of conquest in the Philippines, for example, was termed an Indian war. To prepare myself for teaching more on this topic, I familiarized myself more with Okihiro’s writings and found that he was not only writing accounts of how Pacific Islanders got colonized in a way that both supports and contests the settler colonialism thesis (it’s complicated, say, in Hawai’i), but also talking a lot about the displacement of the myths, stories, and connections to the land and sea as living entities instead of commodified resources. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that he was basically doing some very interesting theology and even making sense of the way that missionaries fit into this complex theological picture of colonialism. I’ve been struggling to write a piece on what I call the ‘postsecular Pacific’ ever since in which I deal with this stuff, and I’m coming to the thought that maybe, as Willie Jennings also says, the moral resistance to logics of settler colonialism are in fact theological, especially as a corrective to what he calls a ‘diseased Christian imagination’ that is about commodifying the land instead of living with it.

I’ve had a number of false starts with reading the literature on settler colonialism and Native Studies. Most of them revolve around a paper that has been rejected more times than I can remember on Cantonese evangelicals and First Nations in Vancouver, where I show that Cantonese-speaking Protestants tend to use their work with First Nations people to posit visions of social justice for Chinese Christians to embrace. I read a bunch of this stuff while revising this paper about three years ago, it didn’t work out, and on top of that, I found the controversy about Andrea Smith’s Cherokee status very confusing. Nevertheless, teaching Asian American studies meant that I kept myself abreast of these fields, especially because they had a lot to do with Pacific Islander history. But recently, I started reading this work in earnest again after I got that troublesome paper accepted for a workshop. The scholars there were kind enough to tell me that the paper is actually about evangelicals, not the First Nations, and in so doing may have saved it from being discarded altogether. However, they did say that the material on settler colonialism might go into future papers and that this critical angle should not be lost, especially as my work develops.

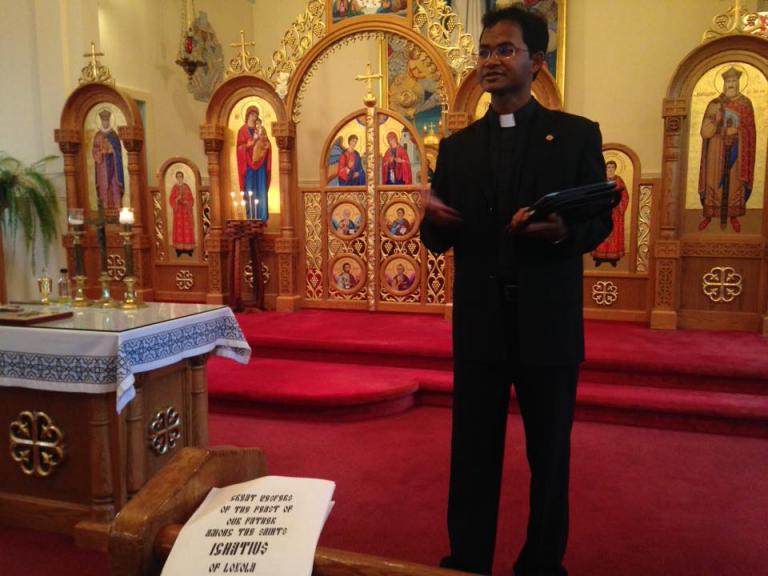

But it was not until very recently that I discovered that I had a spiritual interest in the critique of settler colonialism as well. I should have known better; in December 2016, our temple in Richmond hosted a Vespers of Creation in solidarity with all fighting for ecological justice, especially those at Standing Rock, most especially after we read Fr Kaleeg Hainsworth’s brilliant Orthodox manifesto on ‘water is life.’ But on the Feast of St Ignatius of Loyola last week, our temple also brought in a newly ordained Jesuit priest, Fr Roshan Kiro SJ, during our annual Vespers of St Ignatius to speak on his experience among the indigenous peoples of India, as well as those determined to be in the Dalit caste (if it can even be said that the castes include them). He spoke of a spiritual descendant of the Holy Hieromonks Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier, Fr Constant Lievens SJ, and his fight for these people’s autonomy in terms of land administration. He then set in context the current problem of the far-right Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party in India, more commonly known as the BJP. The real issue was not religious, it seemed. Instead, it was that the BJP seems to have a habit of selling off the lands of the Dalits and the indigenous peoples even despite the presence of people in these groups in the government as civil servants. The people benefitting from this arrangement turn out to be multinational corporations who see these lands as commodities. As Fr Roshan articulated this critique of capitalism, I was struck by the comparisons with Standing Rock – and indeed, also with the protest against the Kinder Morgan pipeline in our neck of the woods on Burnaby Mountain.

What Fr Roshan was articulating was a sense of how settler colonialism works. The smokescreen is a kind of perverse identity politics that calls for the assimilation of indigenous peoples and the creation of a kind of ethnostate by a dominant population. The truth is usually much more perverted: it’s usually that that land has a value for people in the grip of an ideology that turns the material order into fetishized commodities, and the people living on that land are inconvenient barriers to the mining of its resources. When discerning whether a phenomenon is settler colonialism, then, it is important to note that the status of the people being exterminated (e.g. whether or not they are indigenous and what the meaning of indigeneity is) is much less important than the logics of settlement. Settler colonialism is the ideological process of clearing the land from its inhabitants to make living space for a settling population and to mine that place from its resources, sometimes even by bringing in laborers from other places to do the dirty work. Different as Nazism’s ideology of lebensraum, the forced assimilation of indigenous peoples in the America, the Israeli colonization of Palestine, and the BJP’s selling off of Dalit and indigenous lands in India might be in the details, they share a common thread: settlement by mobilizing the apparatus of militarized power to clear the land of its inhabitants.

Hearing Fr Roshan brought me back to the words of one of the members of our Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group, Fr Myron Panchuk. Over the last year, Fr Myron has been organizing commemorations of the Holodomor, Stalin’s artificially created famine in the early 1930s that resulted in the mass starvation of Ukrainian peasants. At one concert that he played a prominent role in organizing, he gave a public address in which he asserted that the Holodomor is a symptom of a modern genocidal tendency, which is not an exaggeration because the scholar who coined the term genocide thought of the Holodomor as fitting the bill. Publicly, Fr Myron stated that our commemoration of the Holodomor must be in solidarity with other peoples who have experienced genocide, including Jews in the Holocaust and Armenians in the early twentieth century, but most especially indigenous peoples in the Americas and Palestinians in territories occupied by the State of Israel. As I listened to Fr Roshan, I began thinking about how what we were discerning is how the genocidal tendency of settler colonialism is the moral crisis of modernity. The philosopher Giorgio Agamben is right when he sees the nomos of the camp as emblemizing the modern: the obsession in modern sovereign power is to create living potential out of bare life, and when that fails, the decision is usually that a bare life is not worth living and should be exterminated. Agamben’s protest against this kind of decision-making, I think, is what distinguishes his Homo Sacer series as a kind of pro-life canon: settler colonialism is immoral – indeed, a grave evil – because the taking of life for the sake of ideology violates the moral order.

A colleague of mine once remarked to me that those of us who work in disciplines promoting social justice agendas have the larger task is the academy of advancing moral reflection. She said that it is surprising how many scholars tend to be amoral in their work, to see their research as not yielding insight into moral questions. Social justice, on the other hand, requires a moral foundation because our argument is that there are immoral structures in society that destroy the integral dignity of the human person and the earth on which we live. In this sense, my reflection as I consider what the Holy Spirit is telling me is that the moral thrust of my work is to discern situations of settler colonialism. What that means, as I have laid out, is to at once protest instances of settler colonialism, but also to think carefully through claims of victimhood. The Catholic claim, for example, is that abortion is a grave evil, but the populist presentation of that statement relies on claims of a genocide of babies in a kind of culture war; the question for discernment is what the actual moral relation between abortion and settler colonialism actually is. The Russian World claim is that they are protecting Russian speakers in Ukraine from a Ukrainian ethnostate, but the real question for discernment is what the relation between Russian World ideology and settler colonialism is. The claim of the State of Israel is that they have a right to land as victims of genocide, but the real question for discernment is the relation between their actual actions in Palestine and the rubrics of settler colonialism. The white nationalist claim is that there is a kind of ‘white genocide’ in which peoples of color are outnumbering and replacing them, but this assertion obscures how whiteness is constitutive of settler colonial ideology and practice.

In this way, what I am beginning to discern that the Holy Spirit is saying about my intellectual agenda is that it has something to do with discerning what settler colonialism is and protesting actual cases of genocide when it is actually happening. This discernment requires attentiveness to complexity and wisdom in distinguishing between claims and real situations. One complication is that the Catholic Church itself, mostly the Latin Church, is accused of advancing a Doctrine of Discovery that was key to the extermination of indigenous peoples, though this ‘doctrine’ is actually an American legal doctrine charted out by the United States Supreme Court. The key word here in this moral thrust of my intellectual work is thus that Jesuit word discernment, and I am both excited and a little possessed by trepidation by how this agenda will shape what I do as an intellectual.