Once upon a time, the Jesuit scholar Matteo Ricci impressed the Ming imperial court with his brilliant memory. His tricks are, of course, no longer just the stuff of legend, but also the stuff of contemporary television drama. Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock doesn’t only deduce who your lover is like Arthur Conan Doyle’s nineteenth-century hero. He has a memory palace where he remembers them, and he fights baddies who also have them and use that information for blackmail.

I have a friend who tells me that my apartment is structured ‘like the inside of someone’s brain.’ I like that, as part of a long-term project that I am working on in my scholarship is a kind of psychoanalytic reading of publics. My friend’s comment was made in relation to all the photos, icons, movie posters and stills, notes, books, and other random things than line the walls of my residence. I thought of this as I got to the end of the Prayers Before Sleep in my Orthodox prayer book and walked around the apartment with my hand cross, blessing it nightly beginning with the four corners of the bed, with words drawn from the Psalm verses used in the Paschal stichera:

Let God arise and let His enemies be scattered, and let them that hate Him flee from before His face. As smoke vanisheth, so let them vanish; as wax melteth before the fire , so let the demons perish from the presence of them that love God and who sign themselves with the sign of the Cross and say in gladness: Rejoice, most venerable and life-giving Cross of the Lord, for Thou drivest away the demons by the power of our Lord Jesus Christ Who was crucified on thee, Who went down to hades and trampled on the power of the devil, and gave us thee, His venerable Cross, for the driving away of every adversary. O most venerable and life-giving Cross of the Lord, help me together with the holy Lady Virgin Theotokos, and with all the saints, unto the ages. Amen.

It occurred to me if my apartment is arranged like the chambers of my brain, going through it with my hand-cross nightly – and then doing it officially when I get my house blessed after Theophany – then it is like an integration of my mental palace and my external residence. This is an especially poignant thought as today is the Forefeast of the Exaltation of the Cross on the Old Calendar, on which our mission worships in the Chicago Eparchy. Of course, the Greek-Catholic Eparchy of Chicago has been famous throughout our global Kyivan Church for our fights about the calendar, so this may give a clue as to who I hang out with in the Eparchy. My only warning to those making assumptions about who constitutes the Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group based on this statement is that the networks that filter through our midst are rather promiscuous.

I too have a memory palace, and I would wager that most people also do. The question, I think, is whether it is well-managed – or to put it in Byzantine terms, whether its economia is organized or left to disarray. In the context of today’s entry into this festal-fasting season of the Holy Cross, a wise priest informed me that it is through prayer that some of what he called the debris of the mind can be put back into its place, or even discarded.

It is the cross, I submit, by which this economia is managed. So much of what is known to be management is of a kind of post-political variety, a kind that substitutes policy for politics. But it need not be this way. Through the cross, my mirrors are broken. The problem with management without the cross is that I become overwhelmed by all the realities I have to manage, even the fictional ones. The cross shatters what our prayers call the nocturnal phantasies, such that they are revealed as irrelevant to the tasks I have at hand. Ave crux, spes unica was the motto of the Congregation of Holy Cross, the Latin order in whose tradition my high school educated me – Hail the Cross, our only hope. It is as the Protestant theologian Jürgen Moltmann insightfully puts it in his classic Theology of Hope, with surprisingly Catholic and even Orthodox themes:

In the Middle Ages, Anselm of Canterbury set up what has since been the standard basic principle of theology: fides quaerens intellectum – credo, ut intelligam. This principle holds also for eschatology, and it could well be that it is of decisive importance for Christian theology today to follow the basic principle: spes quaerens intellectum – spero, ut intelligam. If it is hope that maintains and upholds faith and keeps it moving on, if it is hope that draws the believer into the life of love, then it will also be hope that is the mobilizing and driving force of faith’s thinking, of its knowledge of, and reflections on, human nature, history and society. (Theology of Hope, p. 33).

I scribbled in the margins as I was reading this passage recently that the only Protestant thing about Moltmann is that he seems to think that he’s original. But originality is not the work of theology. What we do is to encounter the living G-d, revealed to us in the Son of Man lifted up upon the wood of the cross, and in this, the fantasies of the demons are negated – stripped of their power, as the Holy Apostle Paul writes to the Church of Colossae. The true meaning, then, of knowing only Jesus Christ and him crucified is that the hope we have is not false. Instead, it has negated falsehood and opened the way to the truth.

The economia of my mind and of my residence is therefore organized in the same way: subjected to the wood of the cross that is exalted over it. By the cross, its fantasy-structures are revealed, transferences exposed, and the truth of my relations revealed. The organizational principle here is to invest my heart into what is actually real, to peel back the layers of secular ideology and to plumb the depths of the supernatural by which the world is truly constituted.

As I came back to my apartment, I had to finish an overdue essay for a publication into which I have been pouring my heart. A closer reading of my recent posts will reveal that I have been thinking about it in the background, and when it is published, I am sure that some of the source material will be seen to have been available here all along. I will not give away its content before it comes out, but I will say that it does concern the musings on the heart that I provided about Chinese Christianity after my friend Faith was received into the Greek-Catholic Church a few weeks ago. As I thought about it, I considered that the perfect epigraph comes from the chorus of the Taiwanese pop star Lee Hom in his song ‘Heartbeat,’ 心跳.

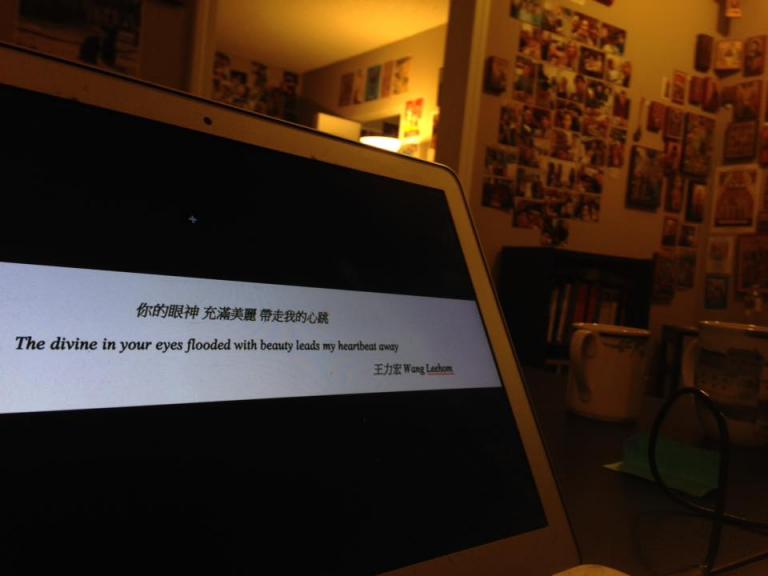

The Chinese of the first line of ‘Heartbeat’ is in Mandarin: 你的眼神 充滿美麗 帶走我的心跳 (ni de yanshen chongman meili daizou wo de xintiao). I struggled to translate it, as the essence of it simply comes out to, Your eyes filled with beauty take my heartbeat away. English is such a boring language, I reflected, and I sought to provide a more awkward and wooden translation to capture the imagery of the Chinese. My first try, displayed in the picture I have provided, was, The divine in your eyes flooded with beauty leads my heartbeat away, with divine in the modern sense of divinity and the older English meaning of being able to discern. A dear friend wrote to criticize me, saying that 眼神 (yanshen) is a colloquialism that really just refers to the expression and essence of the eyes. Of course I know that; this is everyday Chinese language in both Mandarin and Cantonese, and I use it daily. When I submitted the piece, the translation was the spirit of your eyes, with spirit connoting both ‘expression’ and the English sense of faerie too.

Lee Hom, it should be said, is a Christian, probably in a Protestant tradition. The song he has here is not addressed to God, but to a woman he loves – in fact, one with whom he has had a recent series of intimate fights and is begging her to remember how and why they first fell in love. As I mused on the negation of the cross and the importance of holding it over the economia of my mind and of my residence, it also struck me that these words seek to align the heart with the real, instead of the interfering fantasies that get Lee Hom into fights with his beloved. At this intimate level, the importance of crossing the mind with the True Cross is revealed. It is because without such negation, the mind will never be aligned with the heart, and without the stillness that this alignment brings, one will not only be unchaste, but one may as well kiss organization goodbye. What is at stake in discerning the real is nothing short of heart speaking to heart, as opposed to heart consumed by the fictions of fantasy. The economia of the memory palace, it turns out, is not just an impressive trick for expanding the capacity of the intellect. It is to cultivate personal relationships in which contact is actually made with the person and not a figment of the imagination.