The past Thursday was the Feast of the Universal Exaltation of the Holy and Life-giving Cross. For those of us on the quarter system, the school year began on that day. New school years, I find, are like any other kind of new year. The beginning feels fresh, and I find myself with renewed determination. It is only later that I discover that the going is harder than I thought. My students and I joke about a morale dip around week seven. That is the time when people stop showing up to class, people’s grandmas and dogs start dying, and pleas for extensions abound. In fact, I have become, like so many teachers, increasingly convinced that I save the lives of many grandmothers and canines by granting the pedagogical form of the plenary extension – the blanket extension – in most of my classes. I am often driven by pity and compassion in those moments, for only God knows how many editors and colleagues I have petitioned for the same, and how often the deadlines are often miraculously extended at the last minute. By week nine, of course, we are all resurrected. In this sense, the term usually follows what Balthasar called the matrix of redemption:

It just so happens that the beginning of this particular school year has fallen on the Feast of the Exaltation. In reflecting on this coincidence, I found that it offered an opportunity to reflect on what it means for the cross to have brought salvation to the inhabited world, the oikoumēnē that we profess to study, describe, and map as cultural geographers. Certainly, the school at which I teach and do my scholarship does not have a religious affiliation. In my evangelical background – and my evangelical students will be familiar with this – I was informed around the time I was in high school and really got into the currents of American evangelicalism that domain of the secular was supposed to be my mission field, that we were supposed to bring the light of the Gospel to a dark and fallen world because we were the church. It was as if they were giving modern voice to one of the classic moments in my current Byzantine tradition, indeed one that we are celebrating today – the vision of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Constantine of the cross in the sky and the voice that said to him, In hoc signo vinces! In this sign conquer!

As I began to write my reflections, I found that I had to let them sit. I reflected, for example, that I have long been uncomfortable with this ‘mission field’ understanding of the secular world, including the academy, and as I began to write out my relationship to schools throughout my life, they became very long, dense, and tangled. I realized that though I have written quite a bit about my experience of academies both Protestant and Catholic, I had not fully processed my relationship to academia in a more general sense. Writing about them would have taken on a much more confessional tone than even I am comfortable with, so I decided to stop. I began writing them on Thursday proper. I thought I would get them out quickly on the Feast. It is now Saturday, and I realize that I have had to let those thoughts breathe.

I sit and write now, realizing also that this is the work of the Holy Cross: negation. There are several levels of negative thinking here. First, I am negating the school as a mission field. But second, I have also negated my reflections on that negation. The fact is that I do not know what accounts for my discomfort, although I have some suspicions. But to write them as if they were facts would be to overdetermine the case. I need to let them breathe, to live into this time of negation that is the postfeast of the Elevation of the Holy Cross.

And indeed, I have been living. On the Vespers of the Feast of the Exaltation, I made my first visit to a temple in Chicago that was long overdue, the one named for Ss Volodymyr and Olha Equals-to-the-Apostles. I had delayed because everyone had told me I wouldn’t understand the liturgies anyway, as they’d be in Ukrainian. But after my cantoring stint over the summer, I recognized all the melodies as my own and simply basked in the freedom of being able to pray. When I shared that I had gone there, a number of friends noted to me that that is where not only the cabals I hold dear were started – the Kyivan Church Study Group and the Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group – but there were also personal connections to dear colleagues in my field of geographies of religion. I reflected again that this meant that the academy was not my ‘mission field’; if anything, it is more that it constantly intersects with my ecclesial life. I have to let that sit too.

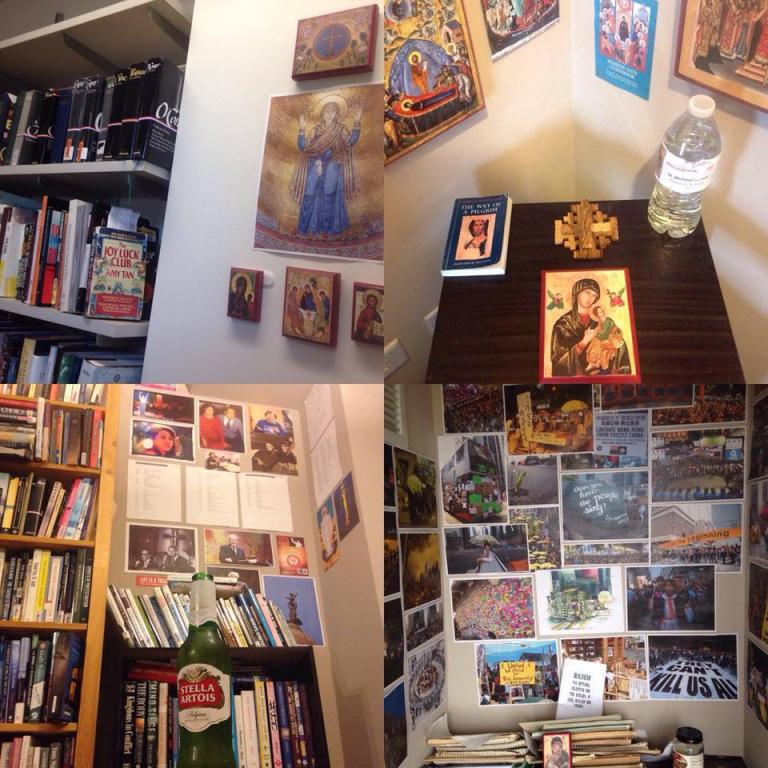

So too, I have spent time at home doing readers’ services for the feast, especially since the postfeast coincides with the fourth anniversary of the start of the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement. As it happens, I brought my icon of the Theotokos of the Passion to my icon corner to commemorate the feast. It so happened that around the time I was doing that, I posted on the Brett Kavanaugh hearings in a facetious way, noting my observations that the sanctioning of his sexual assault was enabled by a culture in the Latin Church during the time he attended high school. I joked that the beer I was drinking on Thursday night was offended to be associated with such misogyny, especially the kind that pervades our sister church. A friend of mine then came onto my Facebook to excoriate me for my negative comments about the Latin Church. He then insisted that the Kyivan Church was ‘under’ the Bishop of Rome and told me to convert back to Protestantism if I didn’t like that Roman Catholicism was not a democracy. I replied to him to read my post on Byzantine democratic polity, but as he did not let up with his vitriol, I told him to come back when he was sober. He took that as an insult and unfriended me, and I have since documented the entire conversation.

As I reflected on that bizarre turn of events – which unfolded very publicly on my social media, which I take to be a public forum (which is why I am not afraid to write about it) – it occurred to me that there was another series of negations at work. I had taken the Virgin Theotokos of the Passion to my icon corner to let her gaze on me during this time of the Exaltation of the Cross. But subconsciously, she has also been a historic conduit between our sister church and us through the order known as the Redemptorists, to whom one of the most stridently papal supremacist bishops of Rome, Leo IX, assigned this icon for safekeeping. To them, she is known as Our Lady of Perpetual Help. It occurred to me that we too have Redemptorists in our own church, especially among those we venerate as New-Martyrs for their suffering under Nazi and Soviet rule in the mid-twentieth century, especially Holy Mykola Charnetsky and Holy Vasyl Velychkovsky.

The Kyivan tradition, as we understand it, is that we are an Orthodox church whose mother is Constantinople, but this cannot be fully lived without the conditions under which we first received the faith – in communion with Rome. The New-Martyrs were tortured for that union, and in that torment, the negation of the cross displayed in the icon that the Redemptorists guard is magnified. We are in communion with Rome, but our love for our sister church comes with a negation that she is our mother and somehow in charge of us, and therefore allows us to issue critiques of her practices without descending into either uniformity or irrational hatred. We are an Orthodox church, but our love for the Byzantine churches is accompanied by a negation of their vitriol about us splitting the Body of Christ through ‘uniatism’; in fact, as Patriarch Sviatoslav said in his most recent meeting with the Bishop of Rome, the greatest act of uniatism in the twentieth century was the Pseudo-Sobor of Lviv in 1946, when Greek Catholics were forced to merge with the Moscow Patriarchate, even though that most certainly is not our mother church. Our polity is ground up and emphasizes the agency of the laity, as we saw most poignantly on the Maidan, but when we live it fully, we are accused by those outside of our church of insubordination – even of Protestantism – with relation to the beloved bishops under whose omophor we rest as weaned children with our mothers. In the vibrant parishes of this church, we encounter the living Christ, but we are framed by all sides as the ethnic chaplaincy of the Roman Catholic Church, which – given how often we repeat that we are a church from Ukraine for the world – is tantamount to slandering us as secular clubs of ethnonationalism.

I reflect that the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross has revealed all these negations that cross my academic and ecclesial life. There is not much more to do, but to sit with these thoughts. The only thing I can confidently say is that the secular academy is not my mission field. It is a realm far too infused with the supernatural for that to be the way to think about it. Indeed, as the icon of the oikoumēnē in my office shows, the entire world is under the sign of the cross, not by way of triumph, but in the sense of the negation that brings order to its economy and ecology. It is with these opening thoughts that I begin my reflections in the time of this postfeast, and I ask for your prayers for fruitful reflection as the quarter begins.