I confess, and do not deny, that I have had difficulty reading the works of the theologian Jon Sobrino, and it is not for want of trying. I have tried to read Christology at the Crossroads on the advice of my spiritual father and just could not get into it. My spiritual father had once been posted to El Salvador as a young Canadian Jesuit, and he had known Sobrino’s friends, the ones who were later murdered as they bridged their teaching at the university with social justice for the community and became New-Martyrs themselves. My dear colleague Sam Tsang wrote an essay in my book Theological Reflections on the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement part on the Hong Kong theologian Kung Lap Yan and his usage of Sobrino’s Jesus the Liberator and Christ the Liberator in his understanding of theologies of liberation in Hong Kong, especially in relation to the Umbrella Movement. I edited the piece to fit Tsang’s Bruce Lee voice – you really should hear him talk, as the similarities are uncanny – but could not get into Sobrino himself. Here at Northwestern, I met the Protestant chaplain Tim Stevens early on in my time here. I learned that he had gone to El Salvador a number of times and was influenced by Sobrino. I appreciate what Stevens has done here at my school, but when I tried to get into Sobrino himself, I could not.

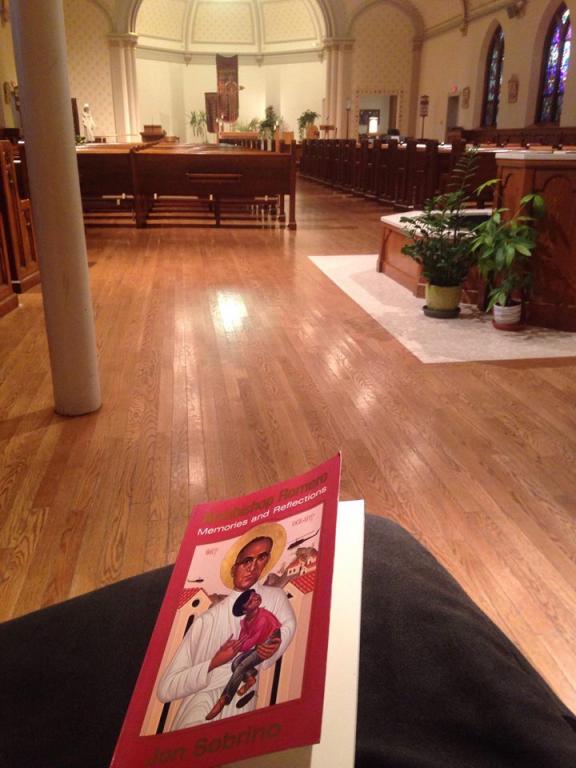

I suppose this is a little strange for someone who professes to be influenced by liberation theology, especially the work of its educational godfather Paulo Freire. But on this afternoon, this eve of the canonization of the New Hieromartyr Óscar Romero in our sister church, I went to the Latin parish closest to my home and office to pray and to do some spiritual reading. I read Jon Sobrino’s Archbishop Romero: Memories and Reflections. Reading with my heart, this is the passage that opened it. Sobrino describes the moment after the murder of Romero’s friend Rutilio Grande SJ, who had been working with the poor. He talks about a mass that Romero offered that combined all of the masses at the cathedral into a single mass that would gather up hundreds of people and have folks spill out the doors and onto the streets, with people from all social classes worshipping together. Reflecting on the planning of that single mass, Sobrino writes on Romero’s theological method and its process of conversion:

But even Archbishop Romero had had his doubts about the single Mass. He was convinced that something dramatic had to be done to stun the country and shake it from its apathy. But he had a theological scruple, which he formulated at our meeting with characteristic sincerity. “If the Eucharist gives glory to God,” he asked, “will not God have more glory in the usual number of Sunday Masses than in just one?”

I must confess that my heart sank to hear him. Here was a theology straight out of the dark ages. But in thinking it over afterwards, and on the basis of all his actions, I finally came to interpret Archbishop Romero’s words correctly. He was only showing his deep, genuine interest in the things of God. His theology was questionable. Beyond question, however, was his profound faith in God, and his surpassing concern for the glory of God in this world.

With the same frank attitude with which Archbishop Romero had propounded his own difficulty, others of us explained our theological reasoning to the contrary. A lengthy discussion ensued. Finally Father Jerez spoke up: “I think Monseñor is absolutely right to be concerned for the glory of God. But unless I am mistaken, the Fathers of the Church said, ‘Gloria Dei, vivens homo‘ — the glory of God is the living person.” Father Jerez’s intervention decided the issue for all practical purposes. Archbishop Romero seemed convinced, and relieved of his scruple. And he decided on the single Mass for that particular Sunday.

At that moment, I thought only that Archbishop Romero had made a lucid, courageous pastoral decision. But afterwards, I thought what it must have meant for him to accept such a novel formulation of what the actual “glory of God” is. At stake had been nothing less than his personal understanding of God — his faith in God. It was not a mere matter of a new theological formulation. It was a matter of a new understanding of God. And Archbishop Romero had accepted that new understanding. Tirelessly he would repeat that nothing was more important to God than the life of the poor. When he went to Puebla, he met Leonardo Boff there, and told him: “In my country, people are being horribly murdered. We must defend the minimum gift of God, which is also the maximum: life.” He himself reformulated Saint Irenaeus’s aphorism, the one Father Jerez had cited, as, “‘Gloria Dei, vivens pauper‘ — the glory of God is the living poor person.” Conversely, he railed against the idols — those false, but real, divinities that deal in death, the deities that call for victims because they live on their blood as the only means to their own survival. (Sobrino, Archbishop Romero, pp. 15-16).

As the canonization draws near, I reflect on this passage, turning it over and over again in my mind. To report the fruits of my contemplations this early would be premature, although certainly the reference to the glory of God may have something to do with my affinity, if not devotion, to Hans Urs von Balthasar. Milbank criticizes Balthasar for being apolitical in his aesthetic reflections, and I can see how a number of Balthasar’s disciples might be wanting in a theology of politics or even be drawn to a kind of conservatism. But Romero extends the Balthasarian reflection on the glory of the Lord, the beauty that ‘is the disinterested one, without which the ancient world refused to understand itself, a word which imperceptibly and yet unmistakably has bid farewell to our new world, a world of interests, leaving it to its own avarice and sadness’ (Balthasar, Seeing the Form, p. 18). Romero’s theology is medieval indeed: he begins with beauty and then locates it in the poor, and Sobrino, a theologian who should be pegged as a Marxist, notices it and dares to play with these formulations that can be construed as conservative, fortifying his commitment to liberation in the process.

There is something poignant about this afternoon reading. When I was a sophomore in high school, I was introduced to liberation theology in a class on Christology where we watched the film Romero, the one starring Raul Julia in the title role. I have an evangelical background. We do not do liberation theology as evangelicals, and I thought that my teacher was quite overly liberal (the word radical was not then in my vocabulary). But watching the film, I was drawn into Archbishop Romero’s world and came to understand the importance of theologies of liberation from a personal perspective. Today, Romero plays the same role in my life. I have struggled to read Sobrino because I read him with my head, attempting to annotate him with my hands. But Romero shows me the way of the heart, and through his icon, I could feel what Sobrino was talking about. The New-Hieromartyr Óscar has opened a door for me. I hope that I will finally be able to walk through it and share in his conversion.