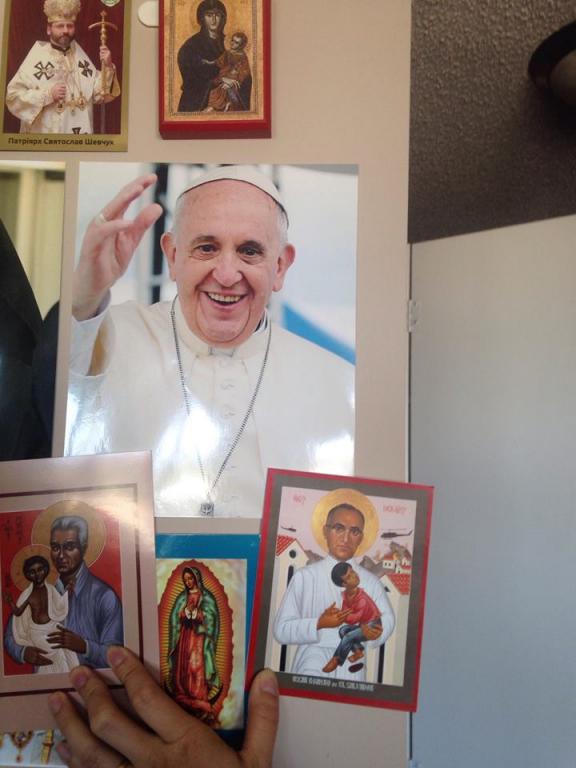

Paul Elie’s piece in The Atlantic on the Bishops of Rome and the Holy New-Hieromartyr Óscar Romero is, simply put, excellent, with most of the nuances that it needs. There are only two addenda I’d add to it.

First, it is certainly true that it was on Ratzinger’s watch under Wojtyła’s pontificate that liberation theology was suppressed. However, their own written records on theologies of liberation are a bit mixed, as is Bergoglio’s himself, with all three frequently making use of the document promulgated by their predecessor Paul VI (who will also be canonized tomorrow) titled Evangelii nuntiandi as a rubric for basic ecclesial communities. Also worth noting is the phenomenal work the philosophers of education Sam Rocha and Adi Burton have done in showing the convergences between Benedict XVI and Paulo Freire on the question of love in liberating pedagogies and even mystagogies.

A better way to see the division is between an emphasis on what John Paul II called the ‘New Evangelization’ (which I would say does not have to be apolitical) and a focus on the theologies of liberation in Latin America. There is indeed a disjuncture between the Latin American bishops’ calls for conscientization at Medellín in 1968 and Puebla in 1979 and their walk-back to focus on a less political evangelistic strategy under the banner of ‘New Evangelization’ at Santo Domingo in 1992. In fact, Cardinal Bergoglio achieved something phenomenal at the fifth Conference of Latin American Bishops’ meeting in 2007 at Aparecida: he managed to frame an agenda for social justice in Latin America in the terms of evangelization. By this, we might understand Francis not so much as a radical, but ever the moderate standing between authoritarian establishment and the people of God. This is an important distinction especially in these contemporary moments when there seems to be a contradiction between Francis’s advocacy for a ‘poor church for the poor’ and the consolidation of power in the Vatican that have led to disasters in China, Ukraine, Chile, and the United States. He is a moderate who is used to being a buffer who is also always thrust into positions of established power but continues buffering.

Following from that first point, my second line of complementary (and indeed, complimentary) critique is that perhaps Elie is making an effort to present the current pope in a good light, which is not something I’ve done in my analysis of Francis and his ideology centered on bishops’ conferences. Elie makes mention of Francis’s ostpolitik with the People’s Republic of China (which is not communist) as well as his checkered record on sex abuse. I suppose there is some cognitive dissonance between those authoritarian moves and his support for the canonization of the Hieromartyrs Óscar Romero and Rutilio Grande SJ. However, the main problem is that conversion stories are seldom convincing. Francis now is the same man as the Bergoglio during the Dirty Wars. No, he probably didn’t sell out his brother Jesuits to the regime, and yes, he really did help a lot of people out. But as this Atlantic piece points out, he also did not stand up to the regime, like Romero did. Romero is what Francis is not, and I think it haunts him right down to the present, especially in his actions right now. It becomes especially clear in Francis’s devotion to Our Lady of Fátima in these times when the Third Secret has been revealed. In that text, the Bishop of Rome is the first to be martyred on a hill by a godless regime wreaking devastation in a ghost town.

Francis’s response to martyrdom in 2015? He says he has prayed for ‘only one favour: that it doesn’t hurt. Because I am a real wimp when it comes to physical pain.’ He is not Óscar Romero, Rutilio Grande, or Ignacio Ellacuría and his companions. They are his guilt complex.