Everything may not turn out perfectly in this life, but by God’s grace everything will be fine. History ends with the triumph of Jesus and the Kingdom of God and so we can take a more optimistic view of life: we are in a divine comedy that might will contain tragedy, but that sorrow will be swallowed up in a great marriage between God and humankind.

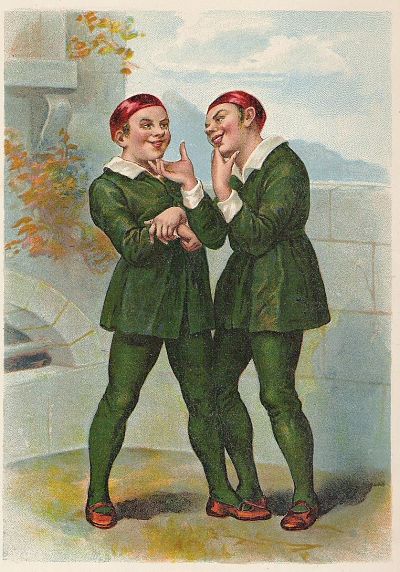

The fact that much of broken, fallen life is a farce leads some of us to despair and darkness, but it made a greater man, a Christian, William Shakespeare laugh at the devils. His Comedy of Errors is a jolly tale that shows that pain can be swallowed up in mirth with a little bit of Providence.

The play starts as if tragedy is coming: Syracuse and Ephesus are in a trade war and instead of merely building a wall, the Ephesians have trumped the Syracusans by executing any Syracusan found in their city. Aegeon is a Syracusan merchant busted by the Ephesians at the start of the play and faces death.

If you want to start a trade war, kill your opponent unless they pay a huge fine, or you are just a poseur selling caps:

If any born at Ephesus be seen

At any Syracusian marts and fairs;

Again: if any Syracusian born

Come to the bay of Ephesus, he dies,

His goods confiscate to the duke’s dispose,

Unless a thousand marks be levied,

To quit the penalty and to ransom him.

Thy substance, valued at the highest rate,

Cannot amount unto a hundred marks;

Therefore by law thou art condemned to die.

Fortunately, Aegeon has a story to tell. He is the father of twins, but he has lost his wife and one of them in a storm. The son left to him has gone to seek his brother and mother and he is now looking for his missing son. Of course, both of the boys were raised with twin servants who also were separated, one to each brother, . . . and if you do not see the comedy of mistaken identities coming . . . then you have never watched a Shakespeare comedy.

Identity is confused and hilarity results, the sort of hilarity that will solve all the problems and rejoin the families. No spoiler is possible for this play, because no other result is possible. The plot seems absurd, but once started in motion would be even more absurd as a tragedy. It just has to work out in the end.

And that is the nature of life. The improbable happens all the time, but we do not see it, because we take our lives for granted. Every miracle of meeting another human seems “normal” to us and we do no appreciate it. Shakespeare tries to jar us out of our lethargy with his improbable play about identity confusion. The Bard knows that we frequently confuse identity: we see a man and think him a slave, a beast, or a tool for our greater glory.

GK Chesterton made a career explicating the simple observation that seeing the “normal” life we lead with new eyes would fill us with wonder. The Comedy of Errors demonstrates this truth. One brother gets to see his wife through the eyes of his sibling. In the midst of the madcap confusion, a character observes:

Am I in earth, in heaven, or in hell?

Sleeping or waking? mad or well-advised?

Known unto these, and to myself disguised!

I’ll say as they say and persever so,

And in this mist at all adventures go.

When we watch or read the play, we know how it should be resolved. We are amused by the errors, the near misses, because we know how it can all be quickly resolved. If all the characters will stop talking, running around, and think, then they will see the improbable has happened. Think of all the improbabilities of daily life that have kept humanity alive and sustained hope for our future despite our errors.

Look around your church and see every member. Think of their qualities. Imagine the odds that just this group of people should get together and how perfect the church could be if everyone recognized their place and role in God’s drama. We are at the right place at the right time. Sin and misfortune separate us, but we are constantly being brought back together so that our errors can become merely amusing and not destructive.

How likely is it that God would become man and become our elder brother? It was so unlikely that the leaders of the people could not pause and see that the improbable had happened. The Brother had come: God in the flesh. They only had to stop to find a feast, but they did not stop.

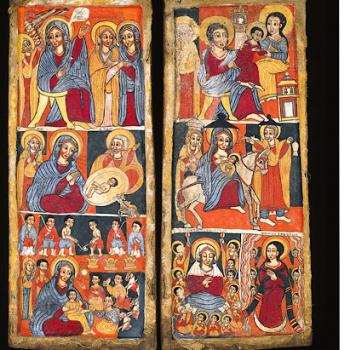

Here is hoping we can do better than those rulers. We can if we, like Mary, will ponder all of God’s improbabilities (that often seem like normal business) in our hearts.

The mother of the “boys” has been a holy abbess in mourning for her husband and son. She appears near the end of the play and begins to unravel the errors and helps turn the potential tragedy into a jolly comedy. She says in her joy:

Thirty-three years have I but gone in travail

Of you, my sons; and till this present hour

My heavy burden ne’er delivered.

The duke, my husband and my children both,

And you the calendars of their nativity,

Go to a gossips’ feast and go with me;

After so long grief, such festivity!

Her children are the age of Christ when he died and was raised to glory. Like Mother Mary, this holy mother has gone from a sword piercing her heart to full joy. She calls the characters to a great feast.

The servants begin to squabble about which is the elder. Who should go first and who will have precedence? The answer is neither:

Nay, then, thus:

We came into the world like brother and brother;

And now let’s go hand in hand, not one before another.

This is just as it must be if there is ever to be peace on earth. We are born “brothers” and must recognize the bond of equality before God and society. We are alike more than we are not alike . . . if aliens were to come to Earth they would struggle to tell us apart. All Earthlings would look alike to them. And so it should be, on one level, for all of us. We have different roles and relationships and confusing those leads to farce, but we are all brothers and sisters.

If we want to win a trade war, we will lose our souls. If we see that economics is not a zero sum game, that we can all win if we deal with justice and equity, then there is hope for fair and free trade. We do not need to “win,” but find brotherhood in a common beneficial relationship. This can happen, because we are different, but also (confusingly!) the same.

God help us to turn the error of our confusion into a comedy and find feasting and joy.

—————————————-

William Shakespeare went to God four hundred years ago. To recollect his death, I am writing a personal reflection on a few of his plays. The Winter’s Tale started things off, followed by As You Like It. Romeo and Juliet still matter, Lady Macbeth rebukes the lust for power, and Henry V is a hero. Richard II shows us not to presume on the grace of God or rebel against authority too easily. Coriolanus reminds us that our leaders need integrity and humility. Our life can be joyful if we realize that it is, at best, A Comedy of Errors.