“Did God get saved between the Old Testament and the New Testament?” asked the student.

“Did God get saved between the Old Testament and the New Testament?” asked the student.

I laughed, but I understood what she meant. God does seem different and not just between the Testaments. His character seems different between the books of Isaiah and Jeremiah! Of course, you can harmonize the picture of God that you find in Exodus with the God of the Gospel of John, but my student is not the first to notice the difference.

My email-friend M*, thoughtful interlocutor that he is, certainly has noticed:

- It seems like God has a very different character or at least very different way of dealing with people in the Hebrew Bible vs. the New Testament. That would seem to make God a moral relativist. Would you agree or disagree with that?

There is a standard (and perfectly fine) way of answering this sort of question that seeks to harmonize the pictures of God we get in the books of the Bible. You can find a good example here. M* seems a bit like I am, however, and always finds explanations, any explanations a bit like a retcon of a science fiction story. The writers do an episode and then later do another clever episode, but that bit creates a plot anomaly. What to do? A super-clever Joss-Whedon-type pulls a harmonization out the air to keep the series going!

The gang on Lost are in purgatory or Bobby was dreaming or Dawn isn’t really Buffy’s sister . . .

Good for television, but not so compelling as a style of argument. In fact, I do not think that these harmonizations are always a retcon when we are dealing with ancient texts. Our ignorance of the ancient world is very great and new facts are discovered that can make old problems, new insights. If you do not know the political situation between Pontius Pilate and Caesar, then some of what is said to Pilate and how he reacts makes less sense than if you understand Pilate was on a short leash with the Boss back Rome.

That’s not retcon, that is deepening our knowledge. One also cannot say that “a” is incompatible with “b” if there is a good, reasonable way to harmonize “a” and “b.” Of course, that harmonization may not be true, but the point is that then textual tension might only be apparent and not actual. Scholars read old books this way. Do not assume Plato is inconsistent if there is a way to harmonize that is natural to the text. Do not assume the Bible is inconsistent either!

And yet . . .

There is always a temptation at a retcon if we love a book, let us accept the premises of M*’s question. Let’s assume that the God of the Hebrew Bible has a very different way of dealing with people than the God of the New Testament. In other words, let us accept all the premises of the question.

I do not think M* has identified a problem for the traditional Christian in any case.

Why?

Often critics forget that each book of the Bible has a human author. The human author is using his best vocabulary to describe what God is telling him. We forget that even a simple concept like “liberty” comes with centuries of linguistic development and intellectual growth. One cannot say a thing in a language if there is no word for the concept in that language! In addition, telling a person to do a “good” thing that will turn out worse, given the culture, for a person is not moral.

Imagine telling a nomadic culture to build prisons! How exactly would that work? How would you explain the concept to them?

If God is in the job of educating humanity to true adulthood, God has had a long hard process. Just getting one nation to grasp monotheism took centuries.

God is not a moral relativist in general, but is in particular.

There are some things that are always wrong**(such as killing innocent people for fun) and there are some things that are wrong only if they are done too much or too little. I should brush my teeth, but not too much. God might tell me to go brush my teeth in one situation and tell me to refrain in another. The morality of tooth brushing is relative to the situation.

Morality can be relative to the situation! If I open the door, that is no sin unless it was to let the killer into the house.

In the Hebrew Bible, God begins with a broken people who no longer recall much of the truth of God’s nature. God reveals that nature to them over time, the best God can without destroying their intellectual integrity. Each lesson opens new doors: think a video game where one level achieved unlocks the next. God educates us in one concept and we give it a “name.” We are ready for the next concept . . . and so it goes.

God deals with the ignorant differently than God deals with the (relatively) more sophisticated. In rough times, with rough men, God spoke roughly. They would have ignored any other Word. In more gentle times, God speaks gently. We get the best Word we can receive. God does not change, but our sophistication does.

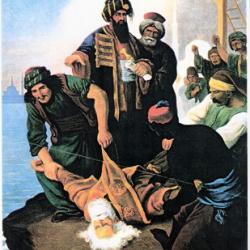

The people in Judges were men of blood and the God they found was a God of blood, just a bit less bloody than Baal. The God they misunderstood, or dimly heard, kept undermining what they thought they heard for what God was saying: love your enemies. The apostle John was a man of thunder with a tender heart and John saw a God with with eyes that were flames of fire, but who told us to love one another.

God does not change, but God changes us. As God changes us, we get a progressive revelation of the person that is God. This person does not contradict the person that we once knew, but refines our knowledge of that person. Barbaric man in all his folly wanted more than an eye for an eye, but God said “no.” More civilized man was happy to take his eye as revenge, but God said “no” in the prophets. Eventually we learned how to show some mercy, not always take the eye, but then God said “love your enemies.”

God shows us the full truth over time: Justice, not revenge. Mercy trumps justice. Mercy washes the world in love.

The changing nature of language and of humankind explains the growing sophistication of our knowledge of God. Atheists are quite wrong: we do not create God in our image, God speaks to us and moves us forward to God’s image. This does not mean that all moral ideas are up for grabs. . . morality narrows, it does not broaden. What God permitted in the past, God forbids today. We have the wealth not to kill, so we must not. We once could marry many, now we see the joys of chastity.

We have been saved, are being saved, and will be saved: not just between Testaments, but in every moment.

—————————-

*M is a non-Christian that sent me 55 questions early this year. He has asked that I not reveal his or her name. I will write as if “he” is a male, but this is for convenience. I do not know if I will get to all his questions. Here are questions 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 17, 23, 26, 27, 28, 34, 35, 37, 44, 47, 54 , and 55.

**I follow Aristotle in Nicomachean Ethics.