Faith is the divine virtue expanding our vision of everything. For those of us who have failed, faith is the substance that disappointed hope finds that helps us live. Faith is rational, passionate, and experiential. Faith moves us to study, love even our enemies, and do works of charity.

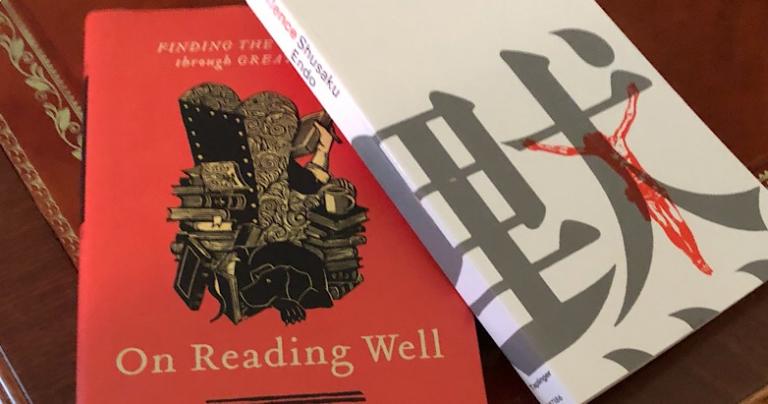

Silence by Shusaku Endo is a piercingly difficult book about faith: difficult to understand, hard on the emotions, and stirring to be a better person. If asked if I agree with Endo’s vision of faith, I would not know what to say. This is not a series of propositions, or an argument, but a picture of reality. Like all pictures of reality, it is limited, perhaps a bit artful, but true. Does a person ask if a picture is true?

Of course it is true, but not the whole truth.

Endo has given us a story of faith: false faith, broken faith, and perhaps faith restored. Karen Swallow Prior (KSP) invites us to consider this account while clearing away some misconceptions.

What is faith?

We can use and know a thing without being able to define it well, but a definition can help us clarify what a thing is not. This has become important regarding faith as weirdlings in both the religious and secular communities have invented definitions of faith that are self-serving.

Of course, anybody can use a term any way they see fit . . . Hurrah for linguistic creativity! We just cannot define a term and then force our definition on everyone else.

What is faith for traditional Christians? Faith is not believing a thing that is impossible that is insanity and if you are in a religious group that says this: leave. If you are skeptic and you think this is what Christian philosophers mean by faith, read some Richard Swinburne.

A problem is that “faith” is used many different ways in English:

We use the word in so many ways. We can have faith in a person or an institution. The law might consider a transaction to be one made “in good faith.” We describe our level of self-confidence as the amount of faith we have in ourselves. But faith as a virtue has a particular meaning, one expressed in the Bible when it explains that faith comes from the grace of God, not from human works (Eph. 2: 8–9). Faith is the “instrument” that brings us to the Christ who saves us.

KSP is defining faith as a divine virtue. Faith is also a cognitive term, an intellectually substantial hope. Sometimes people, including Christian apologists, confuse the two uses and create confusion.

KSP gives us a good breakdown of how faith is often used to avoid any confusion:

Similarly, a colleague who is a New Testament scholar describes faith as having three primary elements: belief (cognitive), trust (relational), and fidelity (obedience). Consider, for example, the faith a child has in a parent: the child may believe that she should trust her parents, and she may obey them, but she may do so without trusting them. On the other hand, a child could believe in and trust her parents—and willfully disobey anyway. Some doubts cannot be expressed apart from faith in God. “Thus, rather than having faith in faith itself, as a point of certainty that relies on our volition only, true faith is a childlike trust in God, who allows his children to question him as they might question their earthly parent, and to do so in the certainty of the relational knowledge and trust of the Father.”

Like any discussion of why we believe what we believe, reason, experience, and personal discipline will never give us certainty through a process.

Doubt (if only in our sanity) is always there, not corrosive skepticism, but humility. We are not God and do not know perfectly.

Plato was helpful to me in understanding the relationship between the “gift of Faith” and cognitive faith. We can reason our way to some truths, like the existence of God or quarks. Doubt will remain, because our arguments are mixed up with personal bias or other limitations we have.

There may come a time, Plato suggests, when after thought and the experience of dialogue in a community that we see. When we see the Good (as he would put it), then all that has come before becomes indubitable to us. This is not accessible to everyone else, they can only see our external experiences and our cognitive work.

That’s good as it (hopefully) shows our sanity!

However, this gift (we cannot make the Good real by words or God reveal Himself to us) is not the product of our work. We can even say “no” to God and so God withdraws Himself from us.

Yet still in this description there is the silence of God that Endo describes with such force. This can be answered intellectually, but if you have not felt this sense of forsakeness, then it cannot be explained or explained away.

Endo does not try and so effectively portrays faith as virtue.

KSP and the Medicine of Silence

Triumph?

Victory happens and triumphant rejoicing is appropriate.

Triumphalism?

That is a heresy and horrible in real life. Ask the suffering Christians of Syria if they can just “name and claim” their way to their best life.

Recall KSP is showing us the virtue of faith, not answers to questions, but living out a wholistic virtue, living in a Divine gift, in a broken world.

Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me a sinner.

Silence is not about answering questions. This is not a work of theology, but a story. Asking for theological precision from it, is like a systemic theology showing good character development.

Our questions may not get answers in a novel. KSP puts it succinctly:

Silence asks a question that is difficult for many readers to answer with certainty: Is the faith of its main character, Father Rodrigues, a saving faith that endures to the end?

But the purpose in reading this novel—or any novel—is not to find definitive answers about the characters. It is rather to ask definitive questions about ourselves. To read about an experience of faith as it falters is an opportunity to seek resolution not in the work of fiction but in the work of our own faith.

KSP is not saying reading a book, this great book or any book, can “produce” the virtue of faith. This is like asking an argument to produce a virtue. However, this work may give us a disposition to receive the gift or encourage us to endure as we seek the virtue of faith.

The book is an experience and one that allows us multiple understandings of the ending. The story presents a chance to dialogue or better to experience one icon of faith: Silence. This is not, thank God, the only such picture or image, since this is a very hard one to see.

Yet life is hard. The image as KSP points out has value even beyond the excellence of the story for many of us. First, this is a Japanese and Christian image, a combination more rare than one would wish. Second, the very difficulty of the image is too rare for many of us. We may be a church of martyrs, but prefer hagiography always. Hagiography is a valuable genre, but Silence is a different medicine for the soul. Third, the style is a particular type of twentieth century writing and many souls find this means of story telling effective for them.

On Reading Difficult Books

Too often we read books as a way of finding support for our particular agenda or point of view. When I do this, I am reading badly.

Why?

The author is not me. He or she is (in a great work of literature) more insightful. As a soul created in the image of God, any human can teach me. When I try to make a book say what I would say, then I end up reading my story with a different voice. I turn what should be a learning experience into literary ventriloquism: great authors made to serve my voice.

God forbid.

Instead, KSP points us to a better way: humility before the text or before other people. We can learn from anyone. This is is difficult for the central character of Silence and KSP points to his inner pride. The people in his flock live miserable lives and he has come to help even though he sees them singing to a martyrdom and meeting spiritual challenges he will fail. He reads them and their lives the way to many of us (God have mercy on me!) read great texts: looking for our mission.

The virtue of Faith will not be controlled. It exists with neither modern ambiguity nor fundamentalist certainty. What is it? God knows. We should seek Him and ask.

KJP reminds us that Silence, like the parables of Jesus, are not a series of propositions:

The truth a parable expresses is not found in a straightforward or literal reading. In fact, the Greek original of the word parable means to “throw beside.” A parable is not an allegory (a form to be discussed in chap. 9), because a parable does not have a one-to-one correspondence of symbolic meaning as an allegory does. Whatever spiritual truth is gleaned from a parable, as in Silence or in Jesus’s story of the wheat and the tares, is less absolute. Like a parable, Silence raises questions even as it offers possible answers.

Christian Tragedy

Life, at least viewed in the context of now, is tragic. KSP points that classical tragedy is not the same as Christian tragedy. Classical tragedy includes catharsis: the reader or theater goer knows what to do.

Ancient society had no basis for eternal hope, the afterlife was grim, so things had to be better now. Classical tragedy always runs the risk of being a drug: we are placated because we are not the tragic hero. We suffer for him, but can (mostly) say: “My life is not so bad. Look at Oedipus!”

Christian tragedy could end differently. We do not think things always work out. Partly this is because we think all people’s stories count. The rich, the men who could afford to go to Greek theater, had lives that often worked out. The slave that made such a life possible or the wife back at the farm had far less to gain from a cheap catharsis.

Christianity demands justice for all, but makes the (seemingly) impossible assertion that everyone’s story matters. Every life counts. As a result, a Christian tragedy cannot trade in cheap catharsis. It must work for all, even those who will wake up in a North Korean prison camp.

KSP:

Silence shares more in common with Christian tragedy. In classical tragedy, closure is contained within the text. Christian tragedy, on the other hand, looks outward, upward, and beyond for redemption. Following a dormant period for drama, the Middle Ages saw a rebirth of tragedy. Since then “Christian life and thought have been the matrix out of which tragedy was reborn. It takes account of the Redemption, the absence of which characterized, in part, pagan tragedy. The tragic event in human life is no longer the final word.” Christian tragedy differs from classical tragedy in its emphasis on “the next world’s destiny being determined in the present one,” thus making it “infinitely more intense and serious than any other mode of tragedy.”

KSP concludes:

In Silence, the unique particularities surrounding one man’s faith and the testing of that faith provide a strangeness that allows readers to view through a different lens what the virtue of faith looks like as it is being practiced well (or not).

Buy the book.

————————————-

This will be a twelve part series: Introduction, Prudence, Temperance, Justice, Courage, Faith,