We have a Presidential candidate who says we are going to win so much as a nation that we will get tired of winning. On the other hand, he looks like a sure loser in the general election. Should winning (if he can fulfill his promises) or losing (if he can’t beat Hillary) determine if we vote for Donald J. Trump?

We have a Presidential candidate who says we are going to win so much as a nation that we will get tired of winning. On the other hand, he looks like a sure loser in the general election. Should winning (if he can fulfill his promises) or losing (if he can’t beat Hillary) determine if we vote for Donald J. Trump?

For Christians the answer is generally “no.” Winning (whatever that means) is not a good enough reason to support a candidate and losing for the right cause (see the Cross) can end up producing victory. The first question that must be asked is whether the candidate is worthy of rule and the second is whether he can gain power legitimately.

I have met a few people who think things are so bad that they start rooting for apocalypse. They were not very secret in their hopes that Y2K would bring an end to civilization as we know it. They see conspiracies everywhere and forget how good we have it. Compared to most of human history, whoever our American overlords are, they are letting us live very well with a huge amount of liberty.

Is liberty at risk? Liberty is always at risk, but it is most at risk during periods of upheaval. The Christian knows that no form of government is perfect. Democracy can end in mob rule. Republics can degenerate into oligarchies. Monarchies can be dictatorships. Yet chaos is generally worse for the rest of us. Where there are no rules, the people perish. Where there are no rules, terrible dictators will arise.

The rules of the political road are the constitution of the state. In the United States most of our rules are in writing (though not all), in nations like the United Kingdom, tradition and law personified in the monarch define the state. Neither system is perfect, but stability has produced societies that are relatively free and prosperous.

Both states are badly governed. I am no fan of President Obama or of Prime Minister David Cameron both of whom seem feckless in a complicated world. They also are overly friendly to the powerful in the world of big business and big government. Such “friendliness” is always dangerous in a Republican or a constitutional monarchy. Why? It can lead to an oligarchy of the rich and already powerful that oppress the rest of us and create the social tension that becomes the basis for revolution.

As usual, Shakespeare tells us the truth about change in leadership: don’t wish for power and grab it unconstitutionally or you will set up a series of problems that will require blood to clean it up. He used the history of England (simplified for dramatic purposes) to make this point. Richard II was a weak king and his nobility killed him and placed Henry on the throne. Henry IV was more effective, but his leadership was tainted by illegitimacy. When his son, Shakespeare’s hero Henry V, dies young and leaves the throne to a youngling Henry VI, then England is ripe for chaos. The War of the Roses, a massive debacle that cost England her continental possessions, was the result.

Shakespeare shows the dangers of revolution without pretending that bad rulers don’t tempt people to revolt.

Richard II is a bad king. He has useless “favorites” who are exploiting his friendship and harming the kingdom. A bad king makes patriots question their loyalty. When good men like John of Gaunt (a hero in the play) begin to question your leadership, a decent leader changes. Richard II cannot see his foolishness. He loves England and Shakespeare gives him a famous speech describing the glories of the old England. I have seen these words used in pride by Englishmen, but sometimes they forget that old Gaunt is bemoaning the corruption of the land by a king who has sold out the constitution for his own power:

Methinks I am a prophet new inspired

And thus expiring do foretell of him:

His rash fierce blaze of riot cannot last,

For violent fires soon burn out themselves;

Small showers last long, but sudden storms are short;

He tires betimes that spurs too fast betimes;

With eager feeding food doth choke the feeder:

Light vanity, insatiate cormorant,

Consuming means, soon preys upon itself.

This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England,

This nurse, this teeming womb of royal kings,

Fear’d by their breed and famous by their birth,

Renowned for their deeds as far from home,

For Christian service and true chivalry,

As is the sepulchre in stubborn Jewry,

Of the world’s ransom, blessed Mary’s Son,

This land of such dear souls, this dear dear land,

Dear for her reputation through the world,

Is now leased out, I die pronouncing it,

Like to a tenement or pelting farm:

England, bound in with the triumphant sea

Whose rocky shore beats back the envious siege

Of watery Neptune, is now bound in with shame,

With inky blots and rotten parchment bonds:

That England, that was wont to conquer others,

Hath made a shameful conquest of itself.

Ah, would the scandal vanish with my life,

How happy then were my ensuing death!

Read the entire speech. The dying patriot does not hold back. Richard II is shaming the England he loves, but John of Gaunt knows there is no easy solution. You cannot destroy the English constitution that made England to save England.

Of course, Richard II misunderstands the basis of his power. He is king “by the grace of God.” Foolish rulers think this gives them unlimited authority. Wise rulers know this is the ultimate check on tyranny. God cannot be bribed. God does not play favorites. God demands justice. What God gives, God can take away: ask King Saul. Richard does not recognize this fact. He says:

The breath of worldly men cannot depose

The deputy elected by the Lord:

For every man that Bolingbroke hath press’d

To lift shrewd steel against our golden crown,

God for his Richard hath in heavenly pay

A glorious angel: then, if angels fight,

Weak men must fall, for heaven still guards the right.

Richard needed to read his Augustine: God defends the right, but over time. Our right is seldom God’s right. Lincoln put this perfectly when asked if God was on the side of the Union and he responded that he hoped the Union was on the side of God. Lincoln knew that no “side” was perfectly in God’s will, even if one of the causes (like abolition of race based slavery) was in God’s will. Richard presumes on God’s hatred of rebellion and regicide while overlooking his own misrule. His bad rule has made God’s opinion on the status quo complex . . . as it always is.

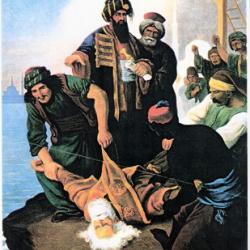

Sadly, John of Gaunt’s son is less wise than his father. Henry is badly treated, but his seizure of power is bad. Henry also presumes to know God’s will, because of Richard’s misrule and his personal popularity and fitness to exercise power. He too easily breaks his oaths and seizes power with the help of unstable men. To keep power, he must murder Richard.

Richard II is an excellent man by the end of the play. The loss of power has been good for him and he gets all the best speeches. He is right that men have sworn oaths to him and right that they are wrong to break them. He is right that God has made him King and finally sees that his own actions have undone his majesty. He says to Henry:

Ay, no; no, ay; for I must nothing be;

Therefore no no, for I resign to thee.

Now mark me, how I will undo myself;

I give this heavy weight from off my head

And this unwieldy sceptre from my hand,

The pride of kingly sway from out my heart;

With mine own tears I wash away my balm,

With mine own hands I give away my crown,

With mine own tongue deny my sacred state,

With mine own breath release all duty’s rites:

All pomp and majesty I do forswear;

My manors, rents, revenues I forego;

My acts, decrees, and statutes I deny:

God pardon all oaths that are broke to me!

God keep all vows unbroke that swear to thee!

Make me, that nothing have, with nothing grieved,

And thou with all pleased, that hast all achieved!

Long mayst thou live in Richard’s seat to sit,

And soon lie Richard in an earthly pit!

God save King Harry, unking’d Richard says,

And send him many years of sunshine days!

What more remains?

His condemnation of Henry in this speech is plain. Henry is an oathbreaker and the rebel will not be able to trust those who made rebellion with him. Richard knows Henry will kill him, but also knows that Henry will always be uneasy in his rule.

Henry is a great man when he is lord and a worse man when he seized the throne. He stops getting the good speeches and becomes a grey and fierce leader. He commits regicide and makes a martyr of Richard to secure the Kingdom. He is fit to rule, but his method of gaining power destroys his fitness.

If a man has to lie, throw his friends aside, cut ethical corners, associate with bad people, and pay bribes to gain power, then the power is not worth having. By the time power is gained, the man is unfit to wield it. Such is the lesson of the Ring of Power in The Lord of the Rings. A good man will be corrupted if he uses a bad thing (the Ring) to do good. He will be better than the Dark Lord at first, but in the end will become a new Dark Lord.

Henry needs his enemies dead, longs to have them dead, but then cannot abide the men who do as he wished. He says:

They love not poison that do poison need,

Nor do I thee: though I did wish him dead,

I hate the murderer, love him murdered.

The guilt of conscience take thou for thy labour,

But neither my good word nor princely favour:

With Cain go wander through shades of night,

And never show thy head by day nor light.

Lords, I protest, my soul is full of woe,

That blood should sprinkle me to make me grow:

Come, mourn with me for that I do lament,

And put on sullen black incontinent:

I’ll make a voyage to the Holy Land,

To wash this blood off from my guilty hand:

March sadly after; grace my mournings here;

In weeping after this untimely bier.

No Christian can read this and think that “winning” is enough. We cannot destroy our morality to save morality. We cannot murder to stop murder as evil men do when they kill an abortionist. We cannot condone immorality and corruption to gain other ends. Henry IV’s son knew that this was true and spent hours in prayer and a great deal of money trying to expiate his father’s sin against England and majesty.

Of course, we all compromise in this broken stupid world. Nobody is just. No ruler is perfect. We ally ourselves to Stalin to defeat Hitler, but there is a line of personal immorality, oath breaking and murder, that a ruler must never cross. He must never corrupt his own soul for the sake of gold and glory.

Rebellion against authority is so dangerous to the soul that it is almost never justified. Christian apologist and the philosopher of the American Revolution John Locke spent pages in his First and Second Treatise showing how a careful group of Christian, conservative, people could replace a ruler. He was successful in showing how revolution might be done properly, but potential revolutionaries should note his cautions and how few historical revolutions have left things better than the revolutionaries found them.

Louis XVI led to Napoleon.

Nicholas II led to Lenin and Stalin.

The Chinese Republic ended in Mao.

Things can get worse whatever political nihilists might think.

Should we vote for Donald J. Trump? We must ask if he is fit to rule and if he can gain and use power constitutionally. If so, we might choose to vote for him. If not, whether he can win or will lose, it does not matter. He cannot get our vote or allegiance.

————————————————

William Shakespeare went to God four hundred years ago. To recollect his death, I am writing a personal reflection on a few of his plays. The Winter’s Tale started things off, followed by As You Like It. Romeo and Juliet still matter, Lady Macbeth rebukes the lust for power, and Henry V is a hero. Richard II shows us not to presume on the grace of God or rebel against authority too easily.