David Russell Mosley

Tenth Day of Christmas

3 January 2014

On the Edge of Elfland

Beeston, Nottinghamshire

Dear Friends and Family,

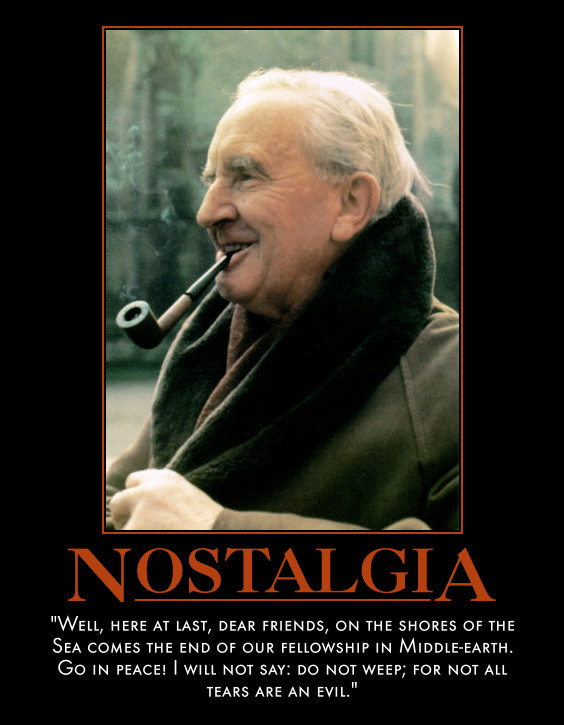

There are a few topics that up until now I have refrained from mentioning in these letters: specifically, homosexuality, abortion, and politics. The first two topics, while often linked quite closely to the third, are frankly too emotional and complicated for me to feel they can be appropriately dealt with in a blog post. The third I avoid often due to ignorance on my part as well as a lack of certainty about where I stand in the midst of the various debates. That being said, since today is J. R. R. Tolkien’s one hundred and twenty-second birthday, I thought I would post some musings on politics/economics garnered from the works primarily of Tolkien, Chesterton, Alison Milbank, and Catholic Social Doctrine.

Pope Francis has recently been under fire from certain Republicans, particularly Rush Limbaugh but comments have been made by John McCain and Sarah Palin as well as many others. The reason the Pope has caused such an uproar is for his indictment of trickle down economics and the mistreatment/oppression of the poor. Francis’s ideas are not new, the Old Testament Prophets are particularly interested in the care for the poor and oppressed. However, it is not just the Bible but the Catholic Tradition that finds these topics important. Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical Rerum Novarum, wrote about the conditions for the working class and the need for the wealthy and the state not to oppress, but to protect our working classes. Pope Leo XIII writing in the nineteenth century penned these words which are equally true today: ‘Hence, by degrees it has come to pass that working men have been surrendered, isolated and helpless, to the hardheartedness of employers and the greed of unchecked competition.’ Pope John Paul II in his Centesimus Annus, written for the hundredth anniversary of Rerum Novarum, writes: ‘”If through necessity or fear of a worse evil the workman accepts harder conditions because an employer or contractor will afford no better, he is made the victim of force and injustice.” Would that these words (from Pope Leo XIII), written at a time when what has been called “unbridled capitalism” was pressing forward, should not have to be repeated today with the same severity.’

I bring up these notions of Catholic Social Doctrine because this seems to have been the driving force behind Tolkien’s work (as well as G. K. Chesterton’s). For Tolkien and Chesterton, indeed for most fairy-stories, the economics of Elfland, a play on Chesterton’s ethics of Elfland, is based in gift giving. Gawain and the lord he later learns is the Green Knight he has been sent to seek, share a game in the poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. During his stay at the Green Knight’s castle, each day the knight will hunt and give as a gift whatever he catches. In return, Gawain will give the lord whatever he wins during the day (in the poem he wins kisses from the lord’s wife).

In Tolkien this gift economy sets the rules for birthdays in the Shire. Bilbo is a bit extravagant in giving a gift to every party-goer, but nevertheless, birthdays in the shire centre around gift exchange. What’s more, Shire economy seems to have little to do with money. Some is spent, particularly for Bilbo’s birthday, but it doesn’t seem to be the driving force of the economy or society in the shire; that place seems to be occupied by the consumption of food, alcohol, and pipe tobacco. Alison Milbank writes in her Chesterton and Tolkien as Theologians, ‘The Shire in particular, while having employees, seems to allow its people some land for the odd cow or pig and the appearance of Hobbiton bears some resemblance to the interwoven village, field and homestead pattern that can still be seen today at Laxton in Nottinghamshire, where the old fieldstrip system that allowed country people to be partially independent of a cash economy still survives in a modified form’ (128).

Hobbiton is not a socialist society, there are some people, like Bilbo, who have more than others, like the Gamgees. Yet, there still seems an implicit notion that one can own too much. Farmer Cotton in explaining to the world travelers how things got as bad as they did in the penultimate chapter of The Lord of the Rings notes that Lotho Sackville-Baggins owend, ‘a sight more than was good for him.’ Ted Sandyman in the same chapter is berated for allowing his father’s mill to be sold and torn down in order to make one too large for the needs of the society and becoming a workman in it rather than its owner and master. It seems the Shire is meant to be both a unit, a society that is in some way governed, but governed in such a way that families can remain relatively independent. In this way they can help each other as Farmer Cotton does with Sam Gamgee’s father Ham is thrown out of his home.

Alison Milbank writes concerning Tolkien’s politics, ‘While Tolkien’s political views do not easily correspond to any political party of his day, as a devout Catholic with his own ethnological interests Tolkien in his fiction can be seen as seeking a more humane, less alienated form of sociality in the manner of Catholic social teaching of the early twentieth century, and its emphasis on a middle way between capitalism and communism.’ This is what I’m looking for. My life’s ambition, in many ways, is to be a small holder with my family. To have chickens and pigs and maybe a cow or two and to grow my own fruit vegetables is what I desire. Yet I don’t simply desire this for myself. I would see a society built on living locally, on taking care of each other. I believe this is part, though not the whole, of the vision of the Kingdom of Heaven. This is the Gospel, or at least part of it. We pray in the Lord’s Prayer for God’s Kingdom to come and his will to be done on Earth as it is in Heaven. A middle road between capitalism and socialism, one built on justice and virtue, one built on making virtuous citizens, which is to say citizens who desire to be happy, which is to say citizens who desire the Good, which is to say citizens who desire union with God through Christ in deification, this is the economics of Elfland.

Sincerely yours,

David Russell Mosley