Here’s a study that’s been reported badly in the press (e.g. Washington Times), because what psychologists mean by the term spirituality is not the same as what ordinary people mean by it. It doesn’t mean quite what most people think it does.

So when a study reports that children’s happiness is linked to their spirituality, it only begs the question ‘what do they mean?’ And here’s where it gets interesting.

In the study in question, by Mark Holder and colleagues at the University of British Columbia, they used a standard questionnaire-based measure of spirituality, the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire (SWBQ). This has four components:

- Personal (meaning and value in one’s own life)

- Communal (quality and depth of inter-personal relationships)

- Environmental (sense of awe for nature)

- Transcendental (faith in and relationship with someone or something beyond the human level)

You can see that only the last one, Transcendental, means anything like the conventional meaning of the term ‘spiritual’.

They gave this questionnaire to 320 children aged 8-12 from a mix of state and faith schools. They also gave them a questionnaire on their religiousness (which measured their beliefs and practices) and a battery of three questionnaires on their happiness.

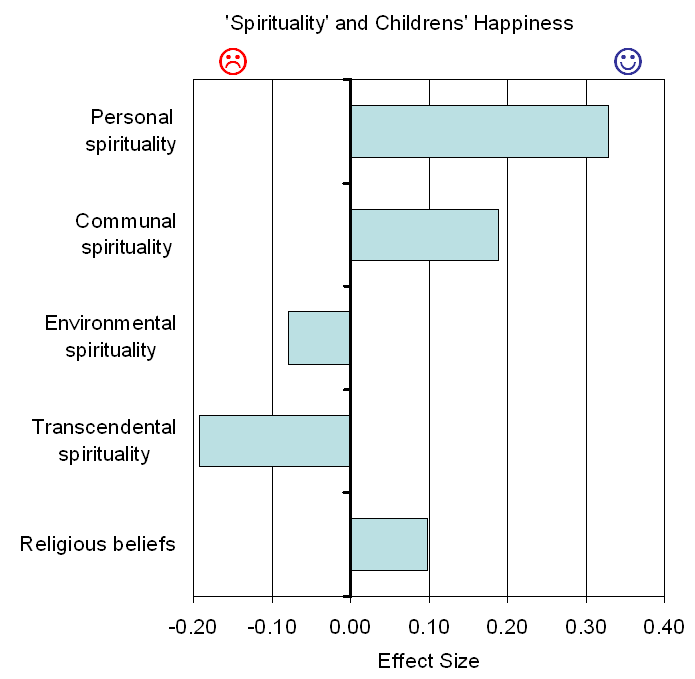

What they found was that there was no correlation between happiness and religiousness, and that the correlation with transcendental spirituality was weak and inconsistent. Environmental spirituality was stronger, but the strongest correlation was with personal and communal spirituality. But there is a problem. Happiness was also linked to personality. If personality and spirituality are connected, then that would skew the results (if, for example, shy children are more spiritual). So they did a hierarchical regression, which corrected for personality and also for sex and type of school.

But there is a problem. Happiness was also linked to personality. If personality and spirituality are connected, then that would skew the results (if, for example, shy children are more spiritual). So they did a hierarchical regression, which corrected for personality and also for sex and type of school.

The results for one of the happiness measures are shown in the figure. The others are pretty much the same – but this is the only one in which transcendental spirituality reached statistical significance.

You can see that personal and communal ‘spirituality’ is really important. They each account for about 5% and 2% of the variation in happiness – which may not sound much but is actually quite a lot by the standards of these kinds of studies. Religion also has a positive effect, but it is small (<0.05%) and probably just a chance effect (it’s not ‘statistically’ significant).

But look at ‘transcendental’ spirituality! It is significant, and the effect is to reduce happiness! The exact opposite of what the news reports would leave you thinking!

So what to make of this? Well, the first lesson is not to trust news reports about studies on ‘spirituality’. Journalists and psychologists mean different things by them.

Secondly, we are starting to get a good grasp on what makes for happy children (all the factors together explain over 20% of the variation in happiness between children). And the answer won’t be a surprise to humanists.

To make children happier, we may need to encourage them to develop a strong sense of personal worth, according to Dr. Mark Holder from the University of British Columbia in Canada and his colleagues Dr. Ben Coleman and Judi Wallace. Their research shows that children who feel that their lives have meaning and value and who develop deep, quality relationships – both measures of spirituality – are happier. It would appear, however, that their religious practices have little effect on their happiness. (ScienceDaily)

Happy children are ones who are loved and valued, who have a strong sense of community and friendship, and who are shielded from excessive spiritual mumbo jumbo.

Mark D. Holder, Ben Coleman, Judi M. Wallace (2008). Spirituality, Religiousness, and Happiness in Children Aged 8–12 Years Journal of Happiness Studies DOI: 10.1007/s10902-008-9126-1