Suppose you’re lost in a strange town and it’s late at night and you see a group of men coming towards you. Do you feel more safe or less safe on knowing they’ve just come from a prayer meeting?

Christopher Hitchens was famously challenged with this question – and swiftly replied that it would be no reassurance to him at all (citing “Mr Paisley’s Martyrs Memorial church in Belfast or a Party of God soiree in Beirut or to the Greater Serbia Church in downtown Belgrade” as examples). There’s a gut feeling here that getting groups of people together to celebrate their religion might not have the great consequences that religious leaders like to believe it has!

But is that so? Religion has been linked with both pacifism and violence in a number of contexts. In the modern world, there’s an urgent need to unravel the apparent links between suicide attacks and Islam. There’s a substantial minority of opinion that says that this link is due to something special about Islam. It’s supposed to be a particularly violent religion.

New research from Jeremy Ginges at The New School in New York pretty convincingly shows that religious beliefs probably have little or nothing to do with it. In fact, it’s all about religious attendance.

In collaboration with Ara Norenzayan at the University of British Columbia, Ginges conducted four studies trying to figure out whether it was beliefs or participation that was most closely linked to support for suicide bombings. In the first two studies, they simply analysed data from existing surveys conducted among Palestinian Muslims. In both studies, frequency of praying wasn’t linked to attitudes to the bombers. But those who attended a mosque every day were roughly twice as likely to support suicide attacks.

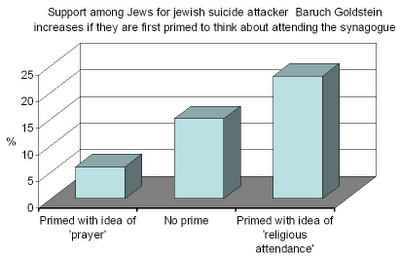

This is interesting, but it might just be circumstantial. So next they tried something rather more clever. They switched their focus to Jewish settlers, rather than Arabs. They phoned up a random selection of people, and asked them about their support for a specific event – the attack by Baruch Goldstein in 1994 in Hebron, which killed 29 muslims. Was this act ‘extremely heroic’ they asked.

Now for the clever bit. For one-third of the sample, they just asked the question straight. For another third, they first asked ‘How often do you go to the synagogue?’ The other third they first asked ‘How often do you pray?’ In other words, they surreptitiously planted in the minds of these people the idea either of attending religious service or going to church.

Now for the clever bit. For one-third of the sample, they just asked the question straight. For another third, they first asked ‘How often do you go to the synagogue?’ The other third they first asked ‘How often do you pray?’ In other words, they surreptitiously planted in the minds of these people the idea either of attending religious service or going to church.

It’s a simple thing, but it had a dramatic effect. Priming people with thoughts of prayer reduced their support for suicide attacks. But priming people with thoughts of going to a religious service increased it. There was a four-fold difference between the two conditions.

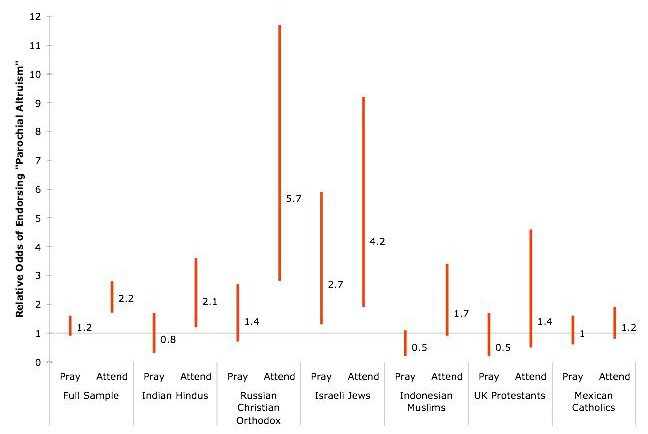

Do these results also hold for people living outside the Palestinian conflict zone? It seems they do. Ginges & co then looked at data from an international survey on religion. This didn’t ask about support for suicide bombers, but it did ask about the feelings towards ‘in-group’ (“I would be willing to die for my God”) and out-group (“I blame people of other religious faiths for much of the trouble in this world”). They called this ‘parochial altruism’ – the idea of sacrificing yourself for your neighbours. Across the six countries they surveyed (including Hindus, Christians and Muslims and Jews), frequent attendance at religious services doubled the support for parochial altruism. Although prayer increased parochial altruism in some countries, overall it had no effect.

Across the six countries they surveyed (including Hindus, Christians and Muslims and Jews), frequent attendance at religious services doubled the support for parochial altruism. Although prayer increased parochial altruism in some countries, overall it had no effect.

What these results are saying is that going to Church, or to a Mosque, Synagogue or Temple creates a ‘coalitional commitment’. On the face of it, this isn’t too surprising. After all, we’re always being told that religion acts to ‘strengthen the community’. And it does. Religious attendance seems to help people to live longer, and to reduce the risk of suicide – presumably by helping them feel part of a special group.

But here we’re seeing the nasty flip-side to group cohesion. Religion also helps people to do all the nasty things that they do as groups. If you want to stop society splitting into ‘us’ and ‘them’, then the first thing you need to do is to reduce – not increase – support for religious groups.

![]() Jeremy Ginges, Ian Hansen, Ara Norenzayan (2009). Religion and Support for Suicide Attacks Psychological Science, 20 (2), 224-230 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02270.x

Jeremy Ginges, Ian Hansen, Ara Norenzayan (2009). Religion and Support for Suicide Attacks Psychological Science, 20 (2), 224-230 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02270.x