Here’s an interesting graph. It’s from a study comparing religious and secular communes in 19th century USA. Michael was talking about this study in the comments so I thought it would be nice to show the data and talk it through.

Here’s an interesting graph. It’s from a study comparing religious and secular communes in 19th century USA. Michael was talking about this study in the comments so I thought it would be nice to show the data and talk it through.

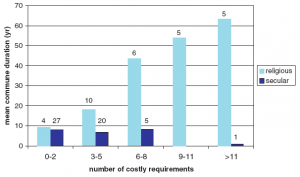

It looks at how long each commune lasted, and compares it with the onerous commitments (everything from giving up certain kinds of food, to abstaining from sex, to cutting ties with the outside world) that each commune demanded from its members.

There’s two things to notice here. First, the religious communes lasted a lot longer than the secular ones. Second, the more ‘costly requirements’ imposed, the longer the commune lasted – but only for religious communes, not secular ones.

What’s going on here? Well, the idea is that the ‘costly requirements’ allow potential members to send a signal. If you are prepared to put up with all the arbitrary rules that make your life difficult, then that’s good evidence that you really, really want to be part of the group. It’s a classic ‘costly signal’.

So why doesn’t it work for secular communes? Sosis argues that religious rituals are more powerful, because of the supernatural connection (p230):

Thus, it appears that the relative success of religious communes is a result of religious rituals and constraints being imbued with sanctity, whereas the rituals and constraints of secular communes are not consecrated. As Rappaport (1971) stated, “to invest social conventions with sanctity is to hide their arbitrariness in a cloak of seeming necessity”

I think that’s part of the explanation. A costly commitment has to be justified if people are going to accept it as a price of group membership. For religious communes, it’s fairly straightforward. You can argue it’s what the god demands – and who can prove otherwise?

For secular communes, there has to be a ‘real world’ justification. If you are going to ask people to hand over their possessions, you’d better have thought through your rationalization pretty well.

You can see this in Sosis’ data. 90% of secular communes have five or fewer costly commitments, whereas half of religious communes have six or more. Secularists simply aren’t attracted to this kind of mentality. It’s a tough sell.

But I also think there’s something else going on here. For people to join a group and stay in it, they have to get something out of it. Crucially, they have to get more out of it than they put in.

For the religious, there’s a lot to gain from being in a religious commune. Typically, they might feel that they’ll be rewarded by their god in this life or the next. And, arguably, the stricter the group the more rewards they might feel they’re going to get.

For the secular, all rewards are solely in the material realm (I don’t mean possessions, I mean rewards like being among friends you can trust). And the potential payoff from group membership has to be greater than the costs of membership.

After all, that’s the whole point of costly signalling. It acts to screen out people who aren’t really committed to the group. For the secular, there just isn’t very much point to being a commune member. It’s a religious idea, which has been taken up by idealistic secularists only for them to see their vision fail.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Sosis, R., & Bressler, E. (2003). Cooperation and Commune Longevity: A Test of the Costly Signaling Theory of Religion Cross-Cultural Research, 37 (2), 211-239 DOI: 10.1177/1069397103037002003

This work by Tom Rees is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.

This work by Tom Rees is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.