This Fridays’ Guardian reports on a new survey which found that a third of doctors in the UK have taken treatment decisions they thought would hasten a patient’s death.

This Fridays’ Guardian reports on a new survey which found that a third of doctors in the UK have taken treatment decisions they thought would hasten a patient’s death.

The sorts of patients we’re talking about here are those who are already near death. Doctors either give doses of pain killers that are high enough to risk causing death, or they withhold treatment that could prolong life.

Around 30% of the doctors surveyed said they had done this at some stage with the expectation that it would cause premature death. Another 7% said that they had done this with the intention of actually causing death. Here’s an example, given in the paper, of withholding treatment with the intention of bringing about an early death:

A doctor working in a critical care unit reported on the care of a woman in her 60s who died in hospital of pneumonia, associated with breast cancer. A decision was made not to use artificial ventilation and various treatments, including oxygen,

renal replacements and cardiac inotropes (drugs that affect the strength of heart contractions) were withdrawn. Morphine was given, with a strong increase on the day of death, and a benzodiazepine.The withholding and withdrawing of treatments were done with ‘the explicit intention’ of hastening the end of life, and the medications given were considered probable or certain to contribute to hastening the end of life. These actions were felt to have shortened life by less than 24 hours.

The reasons given for the withdrawal of therapies included the fact that the patient had pain, other symptoms, had no chance of improvement, that further treatment would have been futile and would have increased her suffering, and that the patient and relatives had asked for this. The decision was discussed with the patient and the discussion included the likely effect on length of life. Discussions with medical colleagues, nursing staff and relatives were also reported.

The patient had made a clear request for the end of her life to be hastened as had relatives and nursing staff. A GP, a specialist in pain relief, and a spiritual caregiver, as well as nurses and relatives had been involved in her care in the last month of life. The doctor had mixed views about euthanasia and physician assisted suicide, feeling that euthanasia in the presence of an incurable and painful illness ought to be allowed, but being opposed to physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia where no such illness was present.

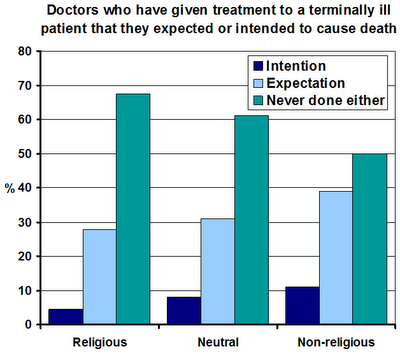

Most of the doctors (65%) were neutral about religion, 21% were non-religious, and 14% were religious. I’ve plotted out the data: as you might expect, the non-religious were much more likely to have prescribed a treatment that they thought might hasten death.

Now, there’s no more analysis than that. It wasn’t a random sample of physicians – neurologists, palliative medicine and care of the elderly specialists were over sampled. And men were more likely than women to have hastened a patients’ death (as well as, presumably, less religious). So we can’t be sure that this is an effect caused by religion.

Still, it seems likely given the strong anti-euthanasia position taken by most religious authorities. And it meshes nicely with the fact that religious patients are more likely to request heroic (but futile) end-of-life treatments.

Of course, end-of-life care is a complicated, multi-dimensional problem. However, in my opinion and the opinion of most humanists, prolonging life to the bitter end, regardless of the consequences for patient and family, may not always be the best course.

Prof Seale, who did the survey, agrees. Here’s what he concludes:

Doctors who said they were religious or who opposed the legalisation of assisted dying were less likely to report decisions where they expected or intended to hasten the end of life. This may be because sanctity of life is a more pressing concern for these doctors than quality of life and may be a cause for concern if this results in patients with similar needs and preferences receiving different treatment.

__________________________________________________________________________________![]()

Seale C (2009). Hastening death in end-of-life care: A survey of doctors. Social science & medicine (1982) PMID: 19837498

This work by Tom Rees is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.

This work by Tom Rees is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.