An earlier post looked at the connection in the USA between religion and a high teen pregnancy rate. High fertility and religion often goes together, and whenever this topic comes up the immediate question is: will the religious inexorably ‘out-breed’ the nonreligious?

The answer to that rather depends on how religion (or lack of it) is transmitted through the generations. Luckily enough, there’s just been a very nice study on this by Vern Bengston, Professor of Sociology at the University of Southern California.

Bengston and colleagues analysed data from the Longitudinal Study of Generations, which has been following over 3000 Californians for over 30 years. They now have over 4 generations in their database.

In 1971, the first year of the study, they surveyed three generations: grandparents (generation 1), parents (generation 2), and children (generation 3). In the paper, they also looked at data from 2000, by which time generation 2 had become grandparents, generation 3 had become parents, and a new generation, generation 4, had arrived on the scene (generation1 seem to have disappeared !).

Over that time, religious affiliation plummeted. In 1971, only 5% of generation 2 (parents) said they were unaffiliated. By 2000, 33% of this same generation were unaffiliated. In generation 4, the non-affiliated rate was 37%.

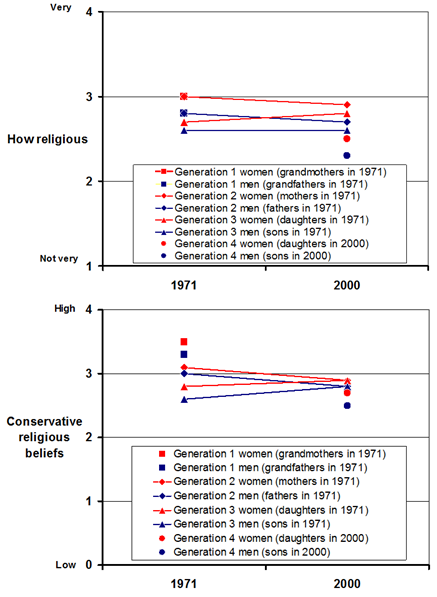

But what about religious beliefs? In each survey, they asked people how religoius they were (on a 1-4 scale), and also a number of questions related to how traditional/literal their religious views were. The results are shown in the first figure. The symbols on the left represent the various generations in 1971, and on the right the generations in 2000. Lines connect generations that appear in both surveys.

The results are shown in the first figure. The symbols on the left represent the various generations in 1971, and on the right the generations in 2000. Lines connect generations that appear in both surveys.

On the whole, people who were surveyed both times haven’t changed much. Mothers and fathers in 1971 are less religious in 2000, and daughters (but less so sons) are more religious.

But the major difference is generational. Grandparents in 2000 are less religious than grandparents in 1971. Parents now are less religious than parents then. And the new generation (generation 4) is least religious of all.

Now, they don’t give any information on how many children the religious participants had compared with the non-religious, but it’s probably safe to assume that they had more.

So, with each generation, the religious have more offspring. And yet their numbers decrease!

This paradox is, of course, easily explained. Although there is a small genetic component that predisposes to agnosticism and atheism, they are in fact social phenomena. Irreligion is not inherited. It’s learned.

This can be seen most clearly with conservative religious beliefs. Twin studies consistently show that this is the component of religion with the largest genetic component. What’s more, conservative Christians have the highest birth rates. Even so, conservative religious beliefs have collapsed with the passing of older generations.

Religion, even conservative religion, is not a gene to be inherited. It’s a meme to be transmitted.

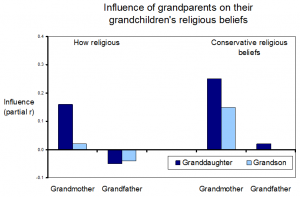

The study had another tidbit of information, and that’s about how much influence grandparents have over their grandchildren’s religiosity. The answer: not a lot. What we’re looking at in this graph is the correlation between the religion of the grandparents and that of the grandchildren, after adjusting for the religion of the parents. So this is the direct effect of grandparents, not the indirect effect (via their children and then on to their grandchildren).

What we’re looking at in this graph is the correlation between the religion of the grandparents and that of the grandchildren, after adjusting for the religion of the parents. So this is the direct effect of grandparents, not the indirect effect (via their children and then on to their grandchildren).

In 2000, grandmothers had a little bit of influence over the religion of their granddaughters. That was particularly true for conservative religious beliefs.

But nobody listened to their grandfathers, and grandsons didn’t pay much attention to their grandmothers.

What’s surprising is how this has changed from 1971. I haven’t done a graph for these data, but basically in 1971 grandparents influenced their grandchildren’s church attendance, but less so their beliefs – and they had absolutely no effect over their conservative religious beliefs.

In other words the role of grandparents in transmitting religion has changed completely in the past 30 years – more evidence that the nature of religion in society is changing.

But there’s a bigger message here, and that’s the magnitude of the influence. Even when it comes to grandmothers and their granddaughter’s religiousness, the strongest link, the effect is very weak.

And what this means is that the transmission of religion can be very rapid. The world of our grandparents is already ancient history – at least as far as attitudes and beliefs go.

____________________________________________________________________

![]()

Bengtson, V., Copen, C., Putney, N., & Silverstein, M. (2009). A Longitudinal Study of the Intergenerational Transmission of Religion International Sociology, 24 (3), 325-345 DOI: 10.1177/0268580909102911

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.