You might have seen the recent study which found that the subtle smell of Windex (a brand of window cleaner) makes people more charitable. Time magazine, for one, carried a report – which got up the nose of a writer on the GetReligion blog. Here’s the offending paragraph:

Nevertheless, both morality researchers and olfactory scientists agree that people do strongly associate physical cleanliness with purity of conscience. It is the notion at the heart of adages like “cleanliness is next to godliness” and evidenced by the widespread use of cleansing ceremonies to wash away sins in various religions around the world. (Truth be told, that practice is merely an extrapolation of an evolutionary strategy to avoid disease.)

Well, that doesn’t sound very likely to me either. There is a clear evolutionary link, but it’s not so banal as encouraging people to wash their hand so as not to get sick.

The evolutionary origins of our moral sense is a hot topic at the moment, but what’s becoming clear is that physical and moral disgust are tightly linked (we pull the same faces for both, for example).

Why? Well, moral disgust probably probably evolved out of the neural systems that originally served to provoke physical disgust. And they’re still linked. Which suggests that the reason we associated cleanliness with godliness is down to a neural short circuit – a ‘design’ flaw that reveals evolution at work.

In other words, ritual purification may well stem from the fact we have a cognitive malfunction that makes us associate cleanliness with morality. Assuming that, the interesting question to ask is what the consequences? The ‘Windex’ study suggests that purification has a morality-reinforcing effect, but there may also be a darker side, according to a study published earlier this year.

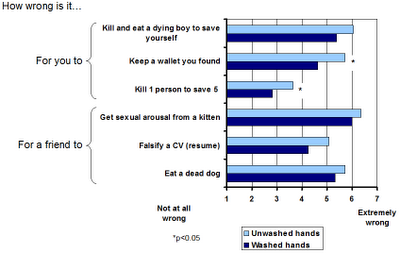

That was a study into the effects of hand-washing, by Simone Schnall and colleagues from the University of Plymouth in the UK. In a cunningly experimental design, they quizzed students on morality – but half of them were asked to wash their hands first (they went through some hoops to make sure the students didn’t think the hand-washing was connected to the experiment).

And here’s what they found. Students with clean hands actually rated a series of morally ambiguous actions as less wrong than students who hadn’t washed their hands.

The difference was particularly big for judgements where the students were asked to imagine themselves doing the action. For example, they were asked to imagine they found a wallet with money in it and the address of the owner, and that they had decided to keep it on the grounds that the owner was rich and they were poor.

Is that an immoral act? Well, it’s questionable, of course, but the point is that those who had washed their hands were less likely to think it immoral.

This result reminds me of other studies which suggest that people who are very firm in their moral convictions are actually more likely to act immorally, and also that we seem to have an internal accounting system that adds up good and bad deeds, and pushes us to do bad or good if we’re getting out of equilibrium.

Maybe if you’re in a clean environment, then you act in a morally clean way. But if you personally are ritually pure, then that makes it easier to do morally dubious things.

__________________________________________________________________________![]()

Schnall S, Benton J, & Harvey S (2008). With a clean conscience: cleanliness reduces the severity of moral judgments. Psychological science : a journal of the American Psychological Society / APS, 19 (12), 1219-22 PMID: 19121126

Liljenquist K, et al (2009). The smell of virtue: clean scents promote reciprocity and charity. Psychological Science in press

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

Schnall S, Benton J, & Harvey S (2008). With a clean conscience: cleanliness reduces the severity of moral judgments. Psychological science : a journal of the American Psychological Society / APS, 19 (12), 1219-22 PMID: 19121126