Here’s a brain-scanning study with a difference. Most such tudies try to work out which parts of the brain are activated when people have religious thoughts. This new one looks at whether religious people have more or fewer nerve cells in different parts of their brains.

Here’s a brain-scanning study with a difference. Most such tudies try to work out which parts of the brain are activated when people have religious thoughts. This new one looks at whether religious people have more or fewer nerve cells in different parts of their brains.

It’s by the team lead by Jordan Grafman that published a study earlier in the year on brain activation. This latest study uses data from the same brain scans.

Basically, the deal is that they boiled their subjects’ religious beliefs down to four factors:

- Intimacy of relationship with God, including praying and religious participation.

- Religiosity of upbringing

- Pragmatism (which covers the sorts of ideas that the non-religious would agree with)

- Fear of God’s anger

Then they looked at the thickness of the cerebral cortex, and measured which bits were thicker (or thinner) in subjects that endorsed each of these beliefs.

The idea is that the thicker bits have more neurones, which means that they work harder. If you know what those regions that have more neurones do, then you can start to figure out what religion (and non-religion) actually is, at least in terms of brain processing.

The first factor, intimacy with god, was greater in people who had more neurones in an area of the brain that deals with interpersonal relationships.

Now, that’s interesting stuff because it shows that people who have a prediliction for feeling intimate with God (praying to god, going to church) may essentially be highly social. The God thing is just an extension of that into the supernatural.

The other interesting thing to ponder, according to the researchers, is that this same bit of the brain is also associated with mental disorders. People with a lot of neurones in this area are at risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder, and people with few neurones are at risk of schizophrenia.

Here’s what they conclude from that:

We speculate that the range of RMTG volumes can be viewed as a spectrum, in which high RMTG volume is associated with stereotyped and ritualistic behavior, high-normal volume is associated with religious behavior (which, we should note, is by definition ritualistic), low-normal volume is associated with non-religiosity, and pathologically low volume is associated with schizophrenia (in which disorganized behavior and aberrant religiosity, with blurred boundaries between the self and God, may occur).

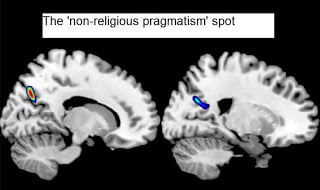

The other interesting factor was number 3 – the ‘non-religious’ factor. This was associated with a part of the brain involved in switching to different perspectives. That suggests that people who are more able to take different perspectives may take a more skeptical, worldly attitude.

Finally, factor 4, fear of god, was associated with fewer neurones in a region associated with empathy and the ability to figure out what’s going on in other people’s minds. It also helps with using memories to deal with current situations. The researchers suggest that people deficient in this region may fear god essentially because they don’t feel confident that they know what god is going to do next.

Now, this is all correlational stuff. It doesn’t tell us whether people are born this way, or if these regions of the brain expand (or contract) as a result of life experiences.

Factor 2, religious upbringing, hit a blank. You could take this to mean that having a religious upbringing does not change your brain in any detectable way. But it might simply be that the bits it changes are the same bits that are associated with religious beliefs.

The researchers draw two overall conclusions from this. Firstly, this is more evidence that there is no special bit of the brain for ‘religion’. Rather, religion taps into neural pathways that evolved for other reasons:

This implies that religious beliefs and behavior emerged not as sui generis evolutionary adaptations, but as an extension (some would say ‘‘by product’’) of social cognition and behavior.

Secondly, the type of god a religious person believes in is a consequence of their underlying neural makeup:

…the current study suggests that evolution of certain areas that advanced understanding and empathy towards our fellow human beings (such as BA 7, 11 and 21) may, at the same time, have allowed for a relationship with a perceived supernatural agent (God) based on intimacy rather than fear.

In other words, it seems that the way a religious person conceives of their god is a reflection of their own ingrained personality.

___________________________________________________________________![]() Kapogiannis D, Barbey AK, Su M, Krueger F, & Grafman J (2009). Neuroanatomical variability of religiosity. PloS one, 4 (9) PMID: 19784372

Kapogiannis D, Barbey AK, Su M, Krueger F, & Grafman J (2009). Neuroanatomical variability of religiosity. PloS one, 4 (9) PMID: 19784372

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.