One in every eight hospitals in the USA is a religious foundation. As with faith schools in the UK, they receive government funding (in the form of Medicare and Medicaid payments, as well as tax-exempt bonds), but they’re allowed to set their own policies to conform with their religious principles.

So, for example, some religious hospitals stop their doctors from providing legal medical treatment, such as contraception, abortion, and certain end-of-life treatment options.

So, for example, some religious hospitals stop their doctors from providing legal medical treatment, such as contraception, abortion, and certain end-of-life treatment options.

This poses a potential dilemma for healthcare providers. A recent survey, by Debra Stulberg, at the University of Chicago, and colleagues, set out to investigate.

They surveyed over 400 doctors, chosen at random [technical note: this wasn’t a completely random sample. To make it statistically robust, they specifically set out to get more doctors with South Asian or Arabic surnames, and they adjusted the results to take this into account].

Just over 40% had worked at one time in a religious hospital. This was pretty evenly spread across age, religious affiliation (or none) and other demographics.

One in five of those who had worked in a religious hospital reported that their treatment decisions had at least sometimes come into conflict with hospital policy. In other words, 20% of doctors in religious hospitals have been prevented from prescribing what they believe to be the best treatment for their patients.

Women were twice as likely as men to have faced this problem (presumably because they are more likely to be dealing with female sexual health). And young doctors were more likely than older ones to have had conflicts with hospital policy.

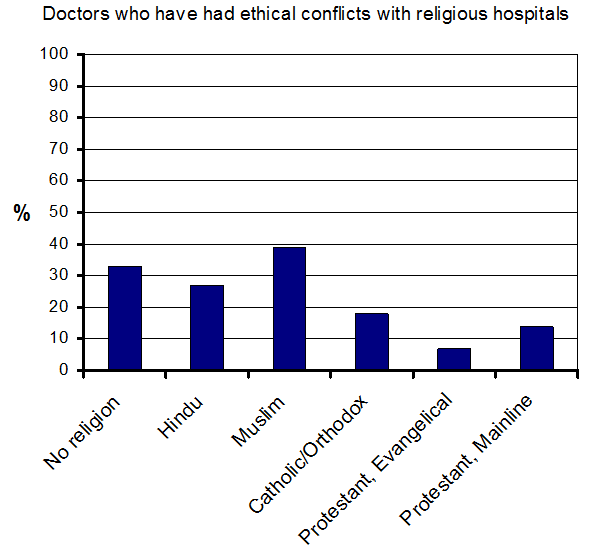

Although you might expect non-religious doctors to be more likely to have problems with the ethics of religious hospitals, it turns out that they are not alone. As shown in the graph, Muslims and Hindus also had problems (contraception is allowed under Islamic law).

In fact, the differences between faiths were not statistically significant (although this may be because the survey was too small).

What did these doctors do when faced with a conflict? Well, almost without exception they complied with hospital policy and denied treatment to their patients.

Here there was a difference between doctors of different faiths. Nonreligious doctors were five times more likely to disobey hospital rules and give the treatment that they thought best. But even so, 90% of nonreligious doctors turned their patients away.

Is this a problem? After all, patients can go somewhere else if they don’t like the hospital’s policy. Well, the problem is that modern medical care is best provided in specialist units. As a result, hospital services are steadily consolidating:

As a result of widespread hospital consolidations many patients, and perhaps particularly those in underserved communities, have fewer choices regarding where to receive health care.

As a result, the authors say:

… patients cared for in a religious hospital or practice who seek time-sensitive but restricted interventions—such as emergency contraception—may face delays as their physicians transfer or refer them to nonreligious institutions. Whether these delays are seen as harmful to the patient depends on one’s beliefs about the intervention itself; even among the authors of this paper, judgments vary.

It seems an oddly paternalistic attitude, in this age of patients’ rights. Which is why, perhaps, young doctors in particular are disgruntled by it.

![]() Stulberg, D., Lawrence, R., Shattuck, J., & Curlin, F. (2010). Religious Hospitals and Primary Care Physicians: Conflicts over Policies for Patient Care Journal of General Internal Medicine DOI: 10.1007/s11606-010-1329-6

Stulberg, D., Lawrence, R., Shattuck, J., & Curlin, F. (2010). Religious Hospitals and Primary Care Physicians: Conflicts over Policies for Patient Care Journal of General Internal Medicine DOI: 10.1007/s11606-010-1329-6

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.