The Indonesian Financial Crisis of 1998 was disastrous for the families caught up in it. The rupiah devalued by 80%, and food prices more than doubled. Worst affected was the price of rice, which rose by 280%.

As a result, the monthly surplus that the average family had to spend on non-food items dropped by two-thirds – from $7.34 to $2.64.

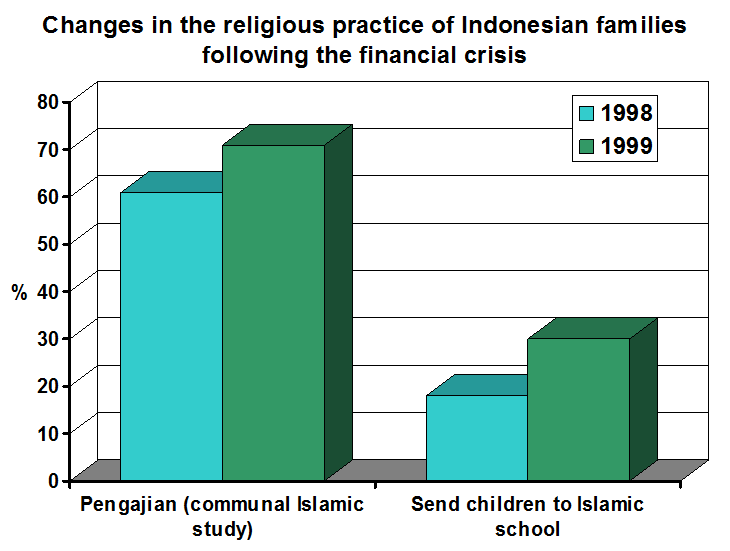

In the period spanning the crisis, the Indonesian Central Statistics Office ran a series of surveys – the Hundred Villages Survey – which followed over 1000 households as they struggled to cope. One of their findings was that, in the aftermath of the crash, Indonesians increased their participation in Pengajian (communal study of the Koran in Arabic), and they were also more likely to send their children to Islamic schools.

In the period spanning the crisis, the Indonesian Central Statistics Office ran a series of surveys – the Hundred Villages Survey – which followed over 1000 households as they struggled to cope. One of their findings was that, in the aftermath of the crash, Indonesians increased their participation in Pengajian (communal study of the Koran in Arabic), and they were also more likely to send their children to Islamic schools.

Daniel Chen, of the University of Chicago, has looked through the numbers in some detail. He was able to pick out those people most exposed to the financial crisis. For example, the wages of government employees were fixed, and so they were hit hard.

What’s more, since the worst inflation was in the price of rice, those people who farmed rice were less affected.

Sure enough, the increases in Pengjian and sending children to Islamic schools were greatest for government employees, and least for rice farmers.

Why this should be? It’s not because people had more time on their hands – other communal activities didn’t increase, and people hit hardest by the crisis actually worked longer hours. And it’s not because Islamic schools are cheaper. In fact, they are more expensive, and what’s more children educated in Islamic schools don’t earn as much when they leave as children who go to secular schools.

It seems to be that religious institutions help to insulate people from the economic shocks. People who increased their religious participation decreased their need to borrow from relatives. What seems to be happening is that religious institution are acting as a kind of localised insurance system, taking from people according to their religious intensity, and redistributing to those in crisis according to their religious comittment.

In other words, religion facilitates the ramping up of ‘group identity’ in response to crisis.

Now of course there are other ways of dealing with financial crisis. Wealthy nations typically do this by various forms of social insurance. And it seems that exactly the same thing did happen in the Indonesian crisis, albeit in a patchy way.

Because in those areas where credit was available (in the form of banks, microfinance institutions, or a rural financial system called ‘BRI loan products’), the effect of financial distress on religious intensity was reduced by 80%.

The Indonesian provides a stark example of how state institutions are in direct competition with religious ones. It’s something to bear in mind as we watch how patterns of religious behaviour change in response to the current crisis.

![]() Chen, D. (2010). Club Goods and Group Identity: Evidence from Islamic Resurgence during the Indonesian Financial Crisis Journal of Political Economy, 118 (2), 300-354 DOI: 10.1086/652462

Chen, D. (2010). Club Goods and Group Identity: Evidence from Islamic Resurgence during the Indonesian Financial Crisis Journal of Political Economy, 118 (2), 300-354 DOI: 10.1086/652462

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.