Previous research has fairly consistently found a small, but statistically significant, link between religion and intelligence. Non-believers score, on average, a few points higher on IQ tests than believers.

But it’s that word ‘average’ that’s the bugbear. Averages don’t tell you much about what’s actually going on with individuals. What’s more, IQ tests are not by any means the full story about intelligence.

Recent research by Sharon Bertsch (University of Pittsburgh) and Bryan Pesta (Cleveland State University), goes some way to putting some fascinating details on the story.

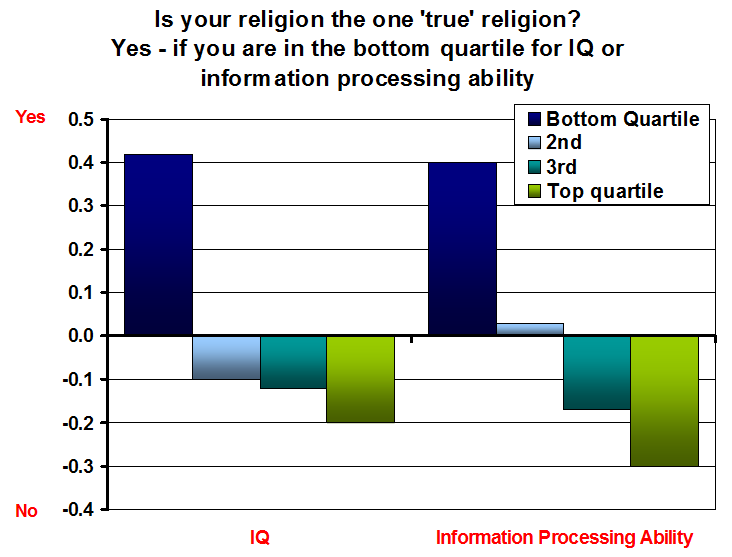

They were interested to know whether the relationship between religion and intelligence is linear, or whether the effects are bunched up at either end of the intelligence spectrum. Maybe being at the high end is linked to non-religion, and the low end to religion, but in the middle – Mr and Mrs Average – there might be no relationship at all between intelligence and religion.

They also wanted to know whether not just abstract reasoning (IQ), but also the ability to process information was linked to religiosity. They did this by testing their ability to rapidly judge the different line lengths, and to pick letter out from a crowd.

They also tested how prone people are to ‘overclaim’. This is a fascinating test where people are presented with facts (a famous person’s name, a scientific concept, or whatever) and they have to say how familiar they are with it. Some of the facts are false, and using some clever processing they can tease out how much the subjects are overclaiming their familiarity with the real facts.

So how did the subjects do? Well, they studied a bunch of undergraduates, so they were a bit smarter than average and none of them were really dumb. Broadly speaking, they confirmed their suspicions: the bottom quartile was the most religious, the top quartile the least, and that there was not too much difference between the two middle quartiles.

In other words, what we have here is an outlier effect. It’s the people on the fringes who are really driving the correlation between intelligence and non-religion.

The effect was strongest for sectarianism – by which they mean the belief that your particular religion is the only true religion. That’s the one shown in the figure. But they got similar results for scriptural acceptance and religious questioning (the brightest quartile were least accepting of scriptural truth and the most willing to question beliefs). And they found the same sort of relationship between information processing ability.

So, the question then is what is really driving this effect? Is it IQ, or is it information-processing ability? Well, they found that, when they lumped both in a statistical model, information-processing ability was actually more powerful as a predictor than IQ. In fact, with information-processing ability in the model, IQ became irrelevant.

Now that’s a remarkable result. Why on earth should judging line lengths, rapidly selecting letter targets, and accurately rating your own familiarity with real-world concepts be linked to non-religion? The authors suggest that these are indicators of the efficiency of neural processing, which in turn might be a building block for the development of more complex cognition and rational thought.

Only more research will tease that one out – and it should be remembered that this research was done in the psychologists guinea pig – mainly white, mainly Christian, US undergraduates. Does it apply to anyone else? Who knows!

On the plus side, however, this is one of the few studies on intelligence and religion that has involved actual lab research, rather than retrospective analysis of data collected for other reasons. That makes it considerably stronger than most studies into this link – albeit for a fairly narrowly defined representation of the human race!

![]() Bertsch, S., & Pesta, B. (2009). The Wonderlic Personnel Test and elementary cognitive tasks as predictors of religious sectarianism, scriptural acceptance and religious questioning☆ Intelligence, 37 (3), 231-237 DOI: 10.1016/j.intell.2008.10.003

Bertsch, S., & Pesta, B. (2009). The Wonderlic Personnel Test and elementary cognitive tasks as predictors of religious sectarianism, scriptural acceptance and religious questioning☆ Intelligence, 37 (3), 231-237 DOI: 10.1016/j.intell.2008.10.003

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.