Let me introduce you to Mr Smart and Heroman. Mr Smart is really, really clever. So clever that he knows everything – like what’s inside a closed box. Heroman is not so smart, but he does have a special power. Heroman has x-ray vision, so that he can see into the closed box.

Here’s a picture of Mr Smart. He looks a bit like a lot of Professors I know.

Here’s a picture of Mr Smart. He looks a bit like a lot of Professors I know.

Both Mr Smart and Heroman had a key role to play in a recent study by Jonathan Lane, of the University of Michigan, and colleagues, into how children come to understand magical beings.

There are basically two schools of thought on this. One is that they have to learn first about ordinary minds and then, building on that platform, they learn about extrardinary minds.

The other school holds that children are born with an inbuilt predisposition to think that all intelligent beings have god-like omniscience. They then have to learn that, sadly, their parents and their friends are in fact limited in what they know.

A leading proponent of this idea is the cognitive psychologist Justin Barrett. His studies of the beliefs of young children have shown that the youngest (aged 3) seem to intuitively believe that all people (and God) are omniscient – they know everything that the child knows. Older children (aged 5) have learned that Mum has her limitations.

The distinction is important. At stake is the issue of whether we are born with an innate predisposition to believe in an Abrahamic god. As Barrett explains:

…early-developing conceptual structures in children used to reason about God are not specifically for representing humans, and, in fact, actually facilitate the acquisition and use of many features of God concepts of the Abrahamic monotheisms (Barrett & Richert, 2003)

But perhaps it’s not that simple. Childhood development is a rapid, complex process. So Lane and colleagues set out to get a bit more granularity into the picture, by learning about the beliefs of children in the middle range, at around 4 years old.

The basic experiment is simple. The experimenter sits with the child and a box of crayons in a room. Except the box doesn’t really contain crayons. it’s got rocks in it instead.

The child knows that, because she’s been shown them. But then the box is closed up again. The question for the child is this: who else will know what’s inside the box, if they come into the room?

Would another girl her age know? Would her mum know? What about Heroman and Mr Smart? What about God?

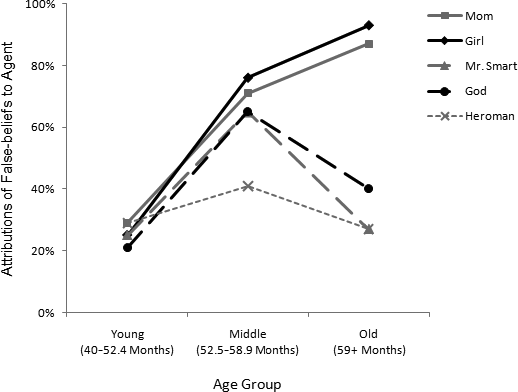

Well, the results change with age, and in a fascinating way. On the graph, higher scores mean that the individual concerned would guess (wrongly) that there are crayons in the box.

The youngest age group, just under 4 years old. mostly think that everyone – Mum, Mr Smart, and God – would know that the crayon box actually has rocks in it.

The middle group, around 4 and a half years old, are more likely to think that they would be fooled, and think (wrongly) that the box holds crayons.

The exception is Heroman. The 4.5-year olds reckon that Heroman could see into the box, and so know that it contains rocks.

The oldest group, around 6 years old, have pretty much all figured out that Mum and the girl would be fooled, but that Mr Smart, Heroman and God would not be.

Here’s what the researchers think is going on. The youngest children have what’s known as ‘reality bias’:

When asked about what other people know or believe, very young children tend to answer by simply assessing reality and using that information to infer others’ knowledge and belief

The middle group, however, have developed enough to understand ignorance:

Soon after children develop an appreciation for the distinction between knowledge and ignorance, they begin to appreciate the distinction between reality and belief; they start to understand that others, misled by inaccurate perceptual cues or outdated information, can hold false beliefs

Only Heroman is not ignorant, because only he can see inside the box.

The oldest children have also learned that some agents – gods and the like – have (or are supposed to have) superhuman knowledge.

Lane concludes that childhood development proceeds in the exact opposite direction to what Barrett proposes. Rather than intuitively understanding the idea of omniscience, children naturally understand all agents – people and magical beings – to be limited in the same way as the people they know.

Realism, in short, is natural. The idea of the supernatural has to be learned.

![]() Lane JD, Wellman HM, & Evans EM (2010). Children’s understanding of ordinary and extraordinary minds. Child development, 81 (5), 1475-89 PMID: 20840235

Lane JD, Wellman HM, & Evans EM (2010). Children’s understanding of ordinary and extraordinary minds. Child development, 81 (5), 1475-89 PMID: 20840235

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.