Aaron Kay a psychologist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada is interested in how people react when you make them feel like they’re not in control of the situation they find themselves in.

He’s previously shown that, if you disturb people’s sense of control, then they tend to compensate by increasing their belief in a controlling god. In a separate study, he also showed that there’s a similar relationship with attitudes to government. What seems to be happening is that, when people lose confidence in their own control, they re-establish their sense of overall control by convincing themselves that some outside agency has control.

Along with some colleagues he’s now shown, in several new studies, that belief in a controlling government and a controlling god seem to be interchangeable. For example:

- In Malaysia prior to a recent national election, people felt that the country was unstable and also their belief in controlling god was high. After the election, belief in governmental stability rose, and belief in a controlling god fell.

- A group of Canadian students who were given a fictitious newspaper article to read (which declared that the minority parties were about to force an election that would result in no clear outcome) had stronger beliefs in a controlling god than students who read an article with a more reassuring message.

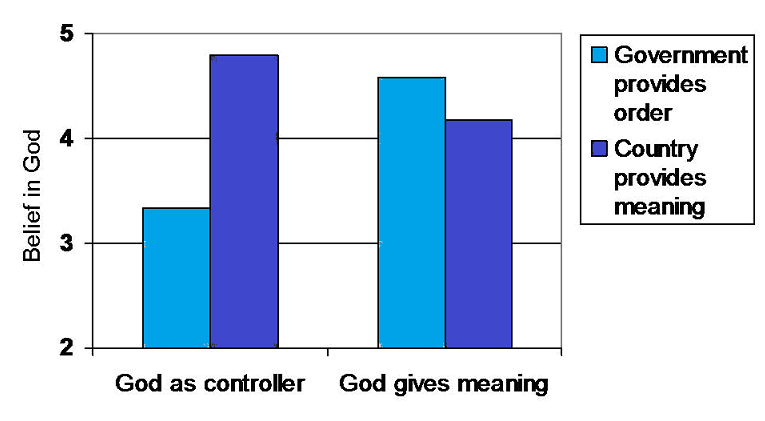

Interestingly, it really does seem to be a belief specifically in a controlling god (or government) that’s important here – other kinds of reassurance just don’t have the same effect. Kay gave students two different articles (allegedly from a Canadian news website). One article presented the government as being very capable and effective. The other talked instead about the importance of Canadian heritage and identity to Canadians – intended to make the reader think that being Canadian is very reassuring and meaningful.

Then they asked about beliefs in a controlling god, and also beliefs in God as a source of personal significance (e.g. God provides answers to questions of meaning and purpose).

As you can see in the figure, the article portraying the Canadian government as effective significantly reduced the strength of beliefs in a controlling God – but had no effect on beliefs in a ‘meaning-giving’ God. The article on Canadian identity had no effect on either kind of god-belief.

In their last experiment, they showed that the effect works both ways: weaken beliefs in a controlling god (by asking students to read an article, ostensibly published in science, attacking the idea) and they are more likely to believe that the Government is doing a good job

If their findings are correct, it suggests that politicians who are in power should attack the idea of a god being in control!

Kay and colleagues do point out that the American Bible Belt seems to contradict this idea. After all, people there are both fiercely patriotic and highly religious. They argue that, if it wasn’t for the patriotism, these folks would be even more religious.

I have to say that I think they’ve missed a key fact about the religious right. Although white evangelical Protestants are fiercely patriotic, they have a deep-seated distrust of their government. According to a Pew survey in March this year, fully 15% of them never trust their government, compared with 7% of the unaffiliated.

In fact, it seems to me that this inverse relationship between trust in god and trust in the government could go a long way towards helping explain why politics in Europe and the USA are so different. Ultra-libertarianism might actually drive people to religion.

![]() Kay, A., Shepherd, S., Blatz, C., Chua, S., & Galinsky, A. (2010). For God (or) country: The hydraulic relation between government instability and belief in religious sources of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99 (5), 725-739 DOI: 10.1037/a0021140

Kay, A., Shepherd, S., Blatz, C., Chua, S., & Galinsky, A. (2010). For God (or) country: The hydraulic relation between government instability and belief in religious sources of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99 (5), 725-739 DOI: 10.1037/a0021140

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.