Spirit possession is common in Uganda, as it is in many parts of the world – especially impoverished areas. It’s a complex syndrome, however, with different spirits have different effects.

In Runyankore, the local language spoken by the Banyankore of Southwestern Uganda, possession by evil spirits is known as Okutembwa and can result in the patient talking in another voice. Possession by the spirits known as Okugwa leads to shaking and falling down. Other spirits can induce a trance-like state.

When asked to explain the causes of possession traditional healers, who are experts in spirit possession, usually give cultural explanations (e.g., neglected cultural obligations and rituals, ancestral spirits, bewitchment) or blame sociocultural conflicts (e.g., disputes over unpaid dowries and land ownership).

But Marjolein van Duijl, who has spent the past 5 years as Head of the Department of Psychiatry at

Mbarara University, noticed that many of the features of spirit possession match up with what Western psychiatrists call dissociation – a disconnect between experiences, thoughts and feelings. It can often result in the feeling that you have been “taken over” by some outside force.

The interesting thing about dissociation is that it’s often caused by traumatic events. So van Duijl set out to discover if traumatic events were the true cause of spirit possession.

With the help of a local team, she interviewed 119 villagers who had been recently treated by local healers for spirit possession, and compared them with a similar group who had not been possessed. She assessed them for symptoms of dissociation, and also quizzed them on traumatic events in their past (using a couple of standardised questionnaires that have been developed specifically for this purpose).

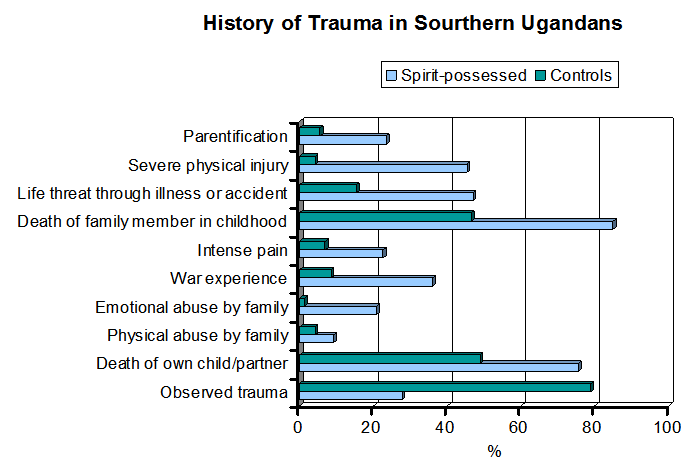

She found that those who were suffering spirit possession did indeed score highly on dissociative symptoms. What’s more, they had experienced far more traumatic events.

You can see an example of what she found in the figure (it’s just a subset of the full findings, to give you a flavour). Pretty much all of the items on this particular trauma questionnaire (the Traumatic Experiences Checklist) were more frequent in those who were possessed (Parentification, by the way, means having to care for your parent when you are only a child – in effect making a parent out of the child).

Traumatic events that directly threatened the life of the individual concerned were particularly common among the possessed.

The strange thing is that the locals were not at all aware of this link. They consistently gave reasonings like “because cultural rituals have not been performed,” or sometimes they blamed obstruction by “the Christian generation,” or said that “It can be a result of unresolved conflicts which the spirits try to settle.”

But if van Duijl is right, then the true cause of spirit possession is, in fact, traumatic experiences that occured in the patient’s past.

Does the misdiagnosis matter? Are these patients having their suffering added to as a result of the misdiagnosis? Maybe not.

“Spirit possession” seems to be a culturally embedded way for a person to manifest their multiple psychological traumatizing events. The rituals around possession may provide a way for the healer and the sufferer to work together to provide a cure. As van Dujil points out:

This also does not imply that all spirit-possessed patients will need their traumatic experiences to be addressed in order to feel better … Remarkably, the vast majority of patients in our study group felt that the treatment by the traditional healer had helped them well (45% felt better and 54% completely healed after treatment).

Given the terrifying situations that so many Ugandans have been exposed to, and the lack of access to modern psychiatric healthcare, the traditional healers seem to be doing a remarkably effective job. They accepting the culturally-embedded interpretations of their patients symptoms, and work with them to effect a cure.

One last thought on all of this. One of the things that struck me was the high levels of trauma experienced even among the controls. To give you an idea of the sorts of harrowing experiences that the people in this study had to deal with, I’m going to leave you with a case that van Duijl reports in the paper:

A 33-year-old woman came to our mental health clinic accompanied by her sister. For many years she had regularly suffered from attacks in which, according to her sister, she displayed aggressive and strange behavior, after which she started talking in different voices, which were not recognized as her own.

These attacks occurred when the family prepared to go to Christian church or to say prayers. During our session, the client shifted into a trancelike state, and started to move her hands like claws and made animal-like noises, after which she began to speak in a strange language and voice. Her sister explained that this was the voice of an uncle who had died many years ago. This uncle still valued traditional cultural beliefs, while their father had turned to Christianity. There had been an unsolved conflict between their father and this uncle as their father refused to perform rituals for the ancestors.

Later during our conversation one leg of the client made involuntary shaking movements. This was distracting the client’s attention. I asked her what her leg was trying to tell us. By bits and pieces the history became clear: The client had been in love for many years with a Muslim man, with whom she had a child. Her father despised the man because of his religion, and her child was forcefully separated from her by her father.

The church attributed her attacks of possession trance states to activities of ‘‘the devil.’’ She had participated in prayer sessions to get rid of these attacks but it had only helped for a short period. We suspected that her attacks, which often occurred when religious activities were performed, were an expression of suppressed anger against her Christian father who had ruined her life because of his rigid principles. Different options for treatment were discussed including traditional healers, counseling and prayer sessions. Although we regularly discussed and referred our patients to traditional healers, in this case the patient preferred to attend counseling sessions to learn to control her attacks and to focus attention on the underlying experience of traumatic loss.

![]() Duijl, M., Nijenhuis, E., Komproe, I., Gernaat, H., & Jong, J. (2010). Dissociative Symptoms and Reported Trauma Among Patients with Spirit Possession and Matched Healthy Controls in Uganda Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 34 (2), 380-400 DOI: 10.1007/s11013-010-9171-1

Duijl, M., Nijenhuis, E., Komproe, I., Gernaat, H., & Jong, J. (2010). Dissociative Symptoms and Reported Trauma Among Patients with Spirit Possession and Matched Healthy Controls in Uganda Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 34 (2), 380-400 DOI: 10.1007/s11013-010-9171-1

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.