On average, the more religious you are, the more kids you’ll have. It’s a widespread phenomenon, seen across pretty much all of the modern world.

The problem is, no-one really knows why this happens.

It could be something about religious beliefs. Maybe they make you more attractive to potential mates, or maybe they drive you to have more kids once you have found your mate.

Or maybe they encourage traditional, rather than modern, approaches to relationships. The traditional role for women is to stay at home and raise children, while hubbie has a career (and the independence and money that goes with it). It works (in theory at least) because divorce is not allowed, meaning that women cannot be left financially adrift.

Women who chose a more modern, more independent lifestyle have to juggle several competing needs. They need to invest time in their own career, and they need to guard against the financial consequences of divorce. In the absence of social structures to give them this security, they will have less time to devote to child rearing.

Could this be what lies behind reduced fertility among the less religious? To find out, Caroline Berghammer, at the Vienna Institute of Demography, took a look at data from the Austrian Generations and Gender Survey. This included 1250 men and women aged 40-45 – i.e. pretty much at the end of their reproductive career.

For each them, the dates of key life events were recorded – the times when they were cohabiting with a partner, when they were married, when they had each child, and when they divorced.

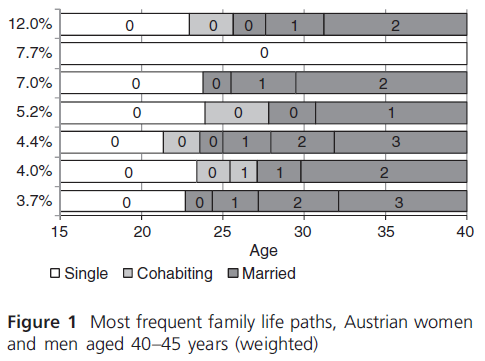

From these data, Berghammer was able to define each individual’s ‘life trajectory’. You can see some examples in the figure.

Take the top row. It describes the life path of someone who was single until age 23, then cohabited for a year before getting married. After a year of marriage, they had their first child and, a couple of years later, their second and final child. This sequence was the most common life trajectory, followed by 12% of those surveyed.

The second row describes an individual who remained single and childless. The third an individual who went straight into marriage, without first cohabiting.

Of course, every individual’s life trajectory is different. But certain patterns emerged, and so Berghammer was able to assign each individual to one of several ‘typical’ trajectories.

The most important of these were the ‘modern’ life (a period of cohabitation before marriage ,but children after marriage) and the ‘traditional’ (marriage without previously cohabitation).

Berghammer found that people following the ‘traditional’ lifestyle were more likely to have 3+ children than those following the ‘modern’ lifestyle. What’s more, traditionalist individuals were more likely to be religious (all Catholic in this analysis).

But – and this is the crucial bit – among those who followed a traditional life path, there was no relationship between their depth of religious belief, or their Church attendance, and the number of children they had.

Exactly the same was seen for those following a modern life path. Although this was more popular among non-religious women, those religious women who did follow this trajectory had no more children than the non-religious.

There was also no difference between the religious and non religious in the chances of remaining single and childless.

Berghammer concludes from this that the critical factor in determining fertility is the choice of life trajectory. Once this has been decided, then religiosity has no further effect on fertility.

So this explains why religious Austrians have more children. It’s because they are more likely to play traditional roles, in which women value childbearing over independence.

![]() Berghammer, C. (2010). Family Life Trajectories and

Berghammer, C. (2010). Family Life Trajectories and

Religiosity in Austria European Sociological Review DOI: 10.1093/esr/jcq052

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.