Back in 2009, I blogged about some then-unpublished studies by Will Gervais, a social psychologist at the University of British Columbia (Why are atheists so disliked). The results suggested that one of the reasons that atheists in the USA are so disliked is because they are distrusted, and that at least part of this distrust was simply because atheists are few and far between – and so they seem strange and unfamiliar.

Gervais has a new paper out that covers some of the same territory but extends it in interesting ways.

In particular, he looked at how distrust varies across countries, depending on how numerous atheists were locally. As predicted, people living in countries with more atheists were more likely to be comfortable with the idea of an atheist President.

In another study, students were asked to read an essay that either told them that there were very few atheists at their university (only 5% of students), or alternatively one that told them atheists were very common (50% of students at their university, and the fourth largest religious group in the world). Sure enough, those students who were told that atheists were common also thought that they were more trustworthy.

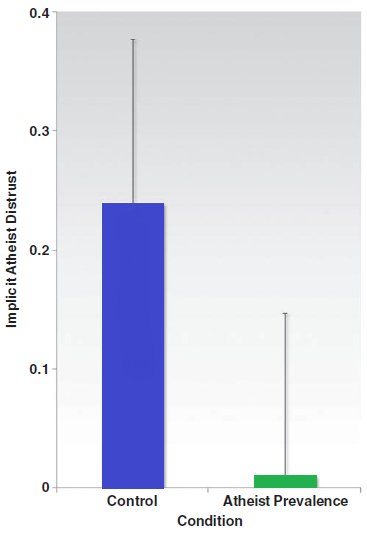

The last study (which was one I briefly mentioned in my last post) used a cunning test (the implicit association test) to find out whether this shift in attitudes was only superficial, or something deeper.

In this test, the subjects are given pictures of two people – one they are told is an atheist, the other a religious person. They then have to categorize words related to trust/distrust when paired with one or the other person. How long takes to do this depends on whether the pairings jar with your preconceptions.

And, as you can see in the graph, their implicit, subconscious trust of atheists really does seem to have been affected by the simple expedient of making them think that atheists are more common than they realised.

So what’s going on here? Well, Gervais outlines all sorts of possible explanations. It might be that if they think that atheists are common, they conclude that some of the people they’ve met around the place must be atheists after all – and they were OK. Alternatively, they might think that, if there are a lot of atheists, then a lot of people must think that atheists are OK. There are various other ways in which simply being more numerous can make a group of ‘others’ seem less weird.

Personally, however, I think there is a special feature of atheism that separates it from many other kinds of predjudice – and that’s the fact that atheism is a choice. When there are only very few atheists, then the only people who are going to ‘come out’ as atheists are likely to be those who are a little maverick.

If lots of people choose to be atheists, then it’s clearly something that ‘normal’ people do. In other words, distrust of atheists when they are a tiny minority might well be a perfectly rational rule of thumb!

![]()

Gervais, W. (2011). Finding the Faithless: Perceived Atheist Prevalence Reduces Anti-Atheist Prejudice Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37 (4), 543-556 DOI: 10.1177/0146167211399583

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.