It’s pretty much taken as an assumption these days that human beings are ‘natural-born believers’. Ask a cognitive scientist who specializes in religion, and they will tell you that our brains are predisposed to all sorts of supernatural concepts.

One consequence of this consensus is a vast outpouring of articles and books pondering over what the evolutionary advantages of religion are. A lot of these explanations are pretty tendentious, and to me it has never seemed likely that this was the whole story.

One popular way to investigate the ‘naturalness’ of religion problem is to see if supernatural concepts are hardwired into children – as you would expect if religious ideas are intuitive and naturalistic ideas have to be learned. Perhaps surprisingly there are very few studies to support this idea – the same ‘classic’ studies keep getting recycled in each new article or book.

And when independent researchers outside the core groups test the hypothesis, they often get results that don’t fit the story. That’s the case with a new study by Jacqui Woolley, a psychologist at the University of Texas.

She and her colleagues read some short tales to a bunch of kids (67 in total) aged 8, 10 or 12, and also 22 adults. All the stories illustrated a ‘difficult to explain’ event.

For example, one featured a guy who steals a little money regularly, until he has enough money to buy a really fast car – which he promptly crashes. Another featured a terminal cancer patient whose cancer went away ‘miraculously’. And another featured a woman who jogged regularly, and yet on her wedding day she tripped and hurt her leg badly – thus making her miss her wedding and also stopped her running. The stories were designed to illustrate events that could be ascribed to moral justice, divine intervention, or luck/fate.

So they read these stories and then asked the listener how the event could be explained. The surprising thing was that the kids hardly ever offered up supernatural explanations. Instead, they would say that maybe the cancer patient slept a lot, which helped her get better. Or, for the athletic woman who tripped on her wedding day, “because she tripped over a rock while she was walking. People usually trip over stuff and fall.”

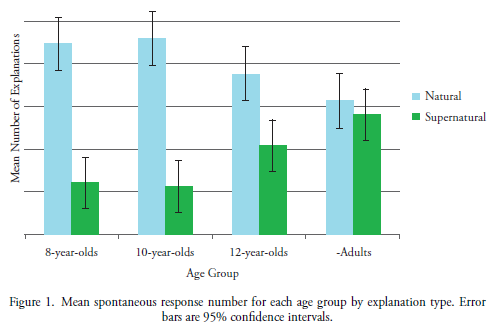

Adults, on the other hand, readily offered up supernatural explanations. There was a clear trend, too, as you can see in the graph – the older the child, the more likely they were to explain these strange happenings by recourse to the supernatural

Then Woolley and Co. put some suggested explanations to them. The kids tended to agree that god or other supernatural explanations were plausible (although they felt that god explanations were more likely for stories with happy outcomes). So it’s not that they aren’t aware of the concepts – it just that they don’t occur to them spontaneously.

Crucially, even the religious kids were more likely to provide naturalistic explanations than supernatural ones. They were, it’s true, more likely to give supernatural explanations than the non-religious, and they were also more likely to give god-based explanations – but according to Woolley even this relationship only becomes significant at around age 12.

This doesn’t of course, mean that humans are not predisposed to think supernaturally. Clearly, in some circumstances we are – and it seems likely that some people are more predisposed to think supernaturally than others.

But what this, along with other evidence, does show is that it is far too simplistic to argue that we are ‘born believers’. In fact, we are born with a wide range of tools with which to understand the world around us, and culture is critical for shaping how those predispositions are shaped into beliefs.

![]() Woolley, J., Cornelius, C., & Lacy, W. (2011). Developmental Changes in the Use of Supernatural Explanations for Unusual Events Journal of Cognition and Culture, 11 (3), 311-337 DOI: 10.1163/156853711X591279

Woolley, J., Cornelius, C., & Lacy, W. (2011). Developmental Changes in the Use of Supernatural Explanations for Unusual Events Journal of Cognition and Culture, 11 (3), 311-337 DOI: 10.1163/156853711X591279

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.