This being the season of good will to all men (at least for those of us with a Christian heritage), it’s time to bring a little harmony to the most tumultuous conflict of our times. Yes, I’m talking about the war between ‘new’ atheists and the religious.

When you see these folks slogging it out on the internet, one regular touch point is over whether religion causes wars – or at least makes them worse.

Of course, we can all cite wars in which the two sides have different religions, but often the two sides differ in lots of other ways. Quite often, what we see is two different ethnic groups fighting. So is religion really contributing to these conflicts, or is it an innocent bystander?

Who is right in the great atheist versus religious battle? Well, the best way to bring some Christmas peace is, of course, to get science to shed some light on the matter. If in doubt, quantify!

Kürşad Turan, at the University of Ankara, has done just this using a database created by the Minorities at Risk project at the University of Maryland. Turan wanted to know whether language barriers or religious barriers were the biggest contributors to ethnic strife. Uniquely, he was able to look at the problem from the perspective of both the ethnic groups and of the State.

First he looked at the factors that contributed to protest and rebellion by ethnic minorities. Here he found that use of different languages by ethnic groups was much more likely to be associated with inter-ethnic strife than religious differences.

In fact, religious differences had a negative effect! If two ethnic groups had different religions, conflict was actually slightly less likely.

When it came to state repression, however, it was a different story. State repression is actually higher in countries where ethnic groups are separated by religion. Language had no effect on state repression. What’s more, state repression of religion increases ethnic conflict, while state repression of language decreases it.

Turan concludes that religion and language play a different roles for ethnic agitators and state repressors. He thinks that states can try to subtly control language, but are more likely to try to co-opt religion. When they repress language, people conform. When they repress religion, people revolt.

Of course, that’s not to say that religion isn’t a flash point between people. There’s an interesting working paper produced by an EU-funded research programme into conflict (actually based at the University of Sussex, just down the road from me). It’s MicroCon Working Paper 18, by Frances Stewart, at Oxford University.

Of course, that’s not to say that religion isn’t a flash point between people. There’s an interesting working paper produced by an EU-funded research programme into conflict (actually based at the University of Sussex, just down the road from me). It’s MicroCon Working Paper 18, by Frances Stewart, at Oxford University.

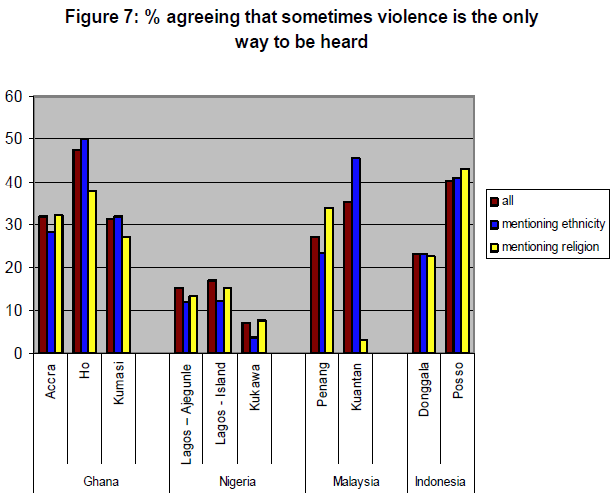

She looked at recent survey conducted in four countries where there is ongoing ethnic strife – Ghana, Nigeria, Indonesia and Malaysia. There were lots of interesting findings, one of which was that religious differences and ethnic differences were about equally often cited as a rationale for violence (as shown in the graphic).

Clearly, then people can be motivated to conflict for either religious or ethnic reasons. But what determines which of the two takes hold in any given location?

Well, based on the interviews that Stewart and her colleagues counducted, she reckons the bottom line is self-interest:

“mobilisation occurred behind the identity which was thought to affect people’s material chances of securing government jobs, contracts etc., rather than behind the identity that appeared to mean most to the people.”

Merry Christmas, everyone!

![]()

Kürşad Turan (2011). Language and Religion: Different Salience for Different Aspects of Identity International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2 (8), 141-152

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.