So, what’s wrong with Muslim countries, eh? That’s something I hear with increasing frequency – usually by people who are implying some kind of cultural superiority over the faithful.

After all, Muslim countries are mostly autocratic, and even after the Arab spring real democracy seems like a distant hope for most.

Among academics, there are two popular theories for why democracy does not take root in Muslim countries. The first says that it’s down to a lack of modernization – stronger economies would “produce a more articulate, liberal, and tolerant public”.

The second theory asserts that Islamic societies don’t embrace the spirit of democracy – that is, they do not score well on essential civic values, such as interpersonal trust, social tolerance, support for political equality, and civic engagement.

To investigate these ideas, ManLi Gu and Eduard Bomhoff (Monash University, Sunway, Malaysia) analysed data from the World Values Survey, hoping to find out whether Muslims support democracy, and why. They looked at a selection of Catholic and Muslim Countries, chosen because there are a number of Catholic countries (in South America) with low levels of economic development.

They used a statistical technique to isolate clusters of opinions. In particular, they were looking at how attitudes to religion cluster with political attitudes.

The first thing they found is that Muslim and Catholic countries had similar levels of desire for democracy, and that all the countries they looked at had a sizable cluster of people who were both highly religious and very much in favour of democracy. What’s more, there didn’t seem to be any notable clusters of religious, anti-democratic individuals (except in Columbia and Mexico).

Incidentally, France, Spain and Uruguay were the only nations to have a sizable non-religious, pro-democracy group – presumably because the other countries had few non-religious people over all.

So, neither religions seem to form an intrinsic barrier to democracy. However, support for democracy was linked with very different attitudes among Catholics versus Muslims.

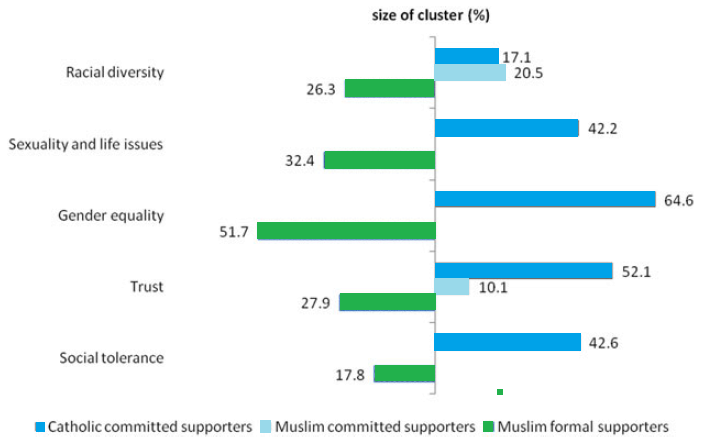

Gu and Bomhoff found that in Catholic countries there were sizeable groups of people whose support for democracy was linked to support for other liberal ideas – such as racial diversity, sexual liberation, gender equality, trust and social tolerance (see graphic).

In Muslims countries, these clusters mostly did not exist. But what did exist was the exact opposite – large groups of people who combined support for democracy with rejection of liberal values!

Further analysis showed that support for democracy in Muslim countries was linked not with liberal values but desire for prosperity and wealth redistribution. They conclude:

Support for democracy in the Catholic countries stems from a pro-democratic civic culture that embodies certain distinct attributes such as tolerance of diversity, mutual trust, and an emphasis on gender equality … Citizens in Islamic countries, on the other hand, endorse the term democracy without necessarily embracing those liberal values that arguably are crucial for a vigorous and open democracy.

So people living in Muslim countries see democracy just as a tool that brings economic benefits. And the problem with that, according to Gu and Bomhoff, is that support for democracy won’t endure in the face of economic downturns.

Now, it was not all that long ago that you could find similar attitudes in Catholic countries. After all, Spain and Latin America have had a pretty ambivalent relationship with democracy until relatively recently. However, attitudes in these countries have shifted quite dramatically in recent years. Democratization was accompanied by a surge in support for liberal values, especially among the young.

In Muslim countries, however, the young are just as conservative as their parents and grandparents (at least, according to the World Values Survey). There are no signs of shifting attitudes.

All of this leads Gu and Bomhoff to a gloomy prognosis for Muslim countries:

We concur with the Culturalist theorists that there is a cultural basis for the absence of democracy in the Muslim world — the democratic deficit has something to do with a shortfall in deeper democratic values and a lack of appreciation of freedom and openness at the mass level.

Quite why this is so is another matter. I suspect it is not due to religious differences – at least, not in any direct way. After all, both religions include traditions that could be called upon to support either liberal or conservative attitudes.

So I suspect that the difference has something to do with the cultural history, and in particular the conflict with the Christian West. Throughout most of the history of Islam, the West was culturally and materially inferior to Islam. Maybe this cultural memory has something to do with the resistance to what are seen today as ‘Western’ values.

![]()

Man-Li Gu, & Eduard J. Bomhoff (2012). Religion and Support for Democracy: A Comparative Study for Catholic and Muslim Countries Politics and Religion, 5 (2), 280-316 : 10.1017/S1755048312000041

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.