Promiscuous teleology is the natty term given to the tendency many people have to see purpose in the world around them. Teleology just means an explaining things in terms of goals or function, and it’s not always wrong. It’s perfectly correct, for example, to say that children wear mittens to keep their hands warm.

But whenever you hear someone say something like “The sun shines on us to keep us warm”, or “Plants make oxygen for us to breath”, that’s promiscuous teleology.

These kinds of explanations are particularly attractive to children, but earlier research by Deborah Keleman at Boston university has shown that even adults succumb to these ideas, particularly when put under time pressure.

Maybe, though, this is just because a lot of adults have dumb ideas about how the world works. What about hard-headed, rational, scientists? Say, physicists – if any group of people in the world knows about cause and effect, it would be them, right?

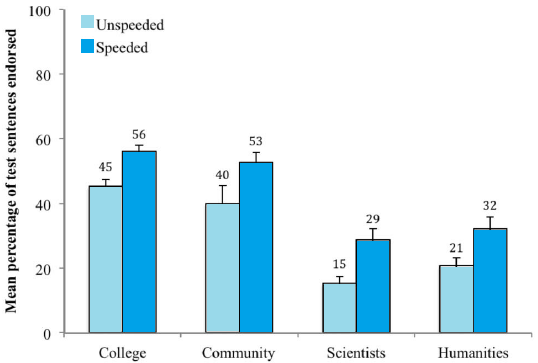

So Kelemen tested 79 active, publishing physicists at high-ranking US universities, and compared their results with 73 actively-publishing humanities scholars, 49 age-matched Bostonians who had bachelor’s degrees, and 179 Boston undergrads.

The set-up was straightforward. A series of statements were flashed up on the computer screen, and the participants had to say if the statements were true or false. The statements they were shown included:

- True, causal explanations, e.g. “Conception occurs because sperm and eggs fuse together”

- True, teleological explanations, e.g. “Children wear mittens in the winter in order to keep their hands warm”

- False, causal explanations, e.g. “Snowflakes are white because they are symmetrical”, and

- False, teleological explanations “Window blinds have slats so that they can capture dust”

In each group, half the subjects were given as much time as they wanted to come up with the right answer. The other half were put under pressure – they each had 3.2 seconds (carefully calibrated to be just enough time for almost everybody to read the sentences, but no more).

So, on to the results!

Well, the good news is that the physicists did better than the undergrads or the local Bostonians. They were significantly less prone than the others to say the false teleological statements were true.

Score 1 for the physicists!

But hold on a moment. Just like everyone else, the physicists were more likely to think that the promiscuous teleological explanations were correct when they put under time pressure. Even though they still did better than the other groups, they were much more likely to get it wrong if they didn’t have time to stop and think.

Why is that? They didn’t have this problem with the causal explanations – they got them right pretty much regardless of the time pressure.

This suggests that even physicists have a sneaking feeling that teleological explanations are right. Even though they know better.

However based on these results, you might conclude that maybe all those years spent studying science and physics have paid off. They’ve given the physicists a better, intuitive understanding of how the world works.

Except that they were no better than the humanities scholars!

Kelemen assessed the scientific knowledge of both groups, and the physicists scored much higher. So, whatever it is that made the scientists better judges than the non-scholars of the true nature of cause and effect, it wasn’t their scientific training.

Perhaps simply being in the habit of spending your time thinking through problems is enough, or maybe it’s down to innate intelligence. Who knows!

But what this does suggest is that there is some kind of ‘default’ predisposition to fall for this kind of dodgy thinking. Even the most hardened rationalists are susceptible, at least to some extent.

Kelemen did discover one other thing. Across all the groups, people who believed strongly in God or who believed that “Nature is a powerful thing” were significantly more likely to be taken in by the false teleology statements.

And that gives us another pointer to why some people believe in god and others do not. And it fits in with earlier research which found that people who have faulty ideas about cause and effect were also more likely to believe in the paranormal.

![]()

Kelemen, D., Rottman, J., & Seston, R. (2012). Professional Physical Scientists Display Tenacious Teleological Tendencies: Purpose-Based Reasoning as a Cognitive Default. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General DOI: 10.1037/a0030399

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.