Chris Burris, at St. Jerome’s University in Canada, has been quizzing students at “a southwestern Ontario university” about their interests in video games and board games. He’s found that atheists were more likely to prefer video games, and his hypothesis as to why this should be is really rather interesting.

So, along with Elyse Redden at the University of Guelph, here’s what they did. They asked 228 students to complete an online survey that asked, among other things, about their liking for four different kinds of video games (strategy, role-play, a narrative [i.e., a story or world to discover], and simulated violence) and the same types of board games.

There were 51 students who said they had “no religion” and the 31 outright atheists. Everyone else (Christians Jews, Muslims, whatever) went into the “religious” bucket.

All groups preferred video games over board games, but for the atheists the gap was much larger. Also worth noting is that the atheists liked both kinds of game more than the religious did – although the difference was pretty marginal for board games.

But Burris noticed something else. Alongside game preferences, he also asked questions that sought to uncover their imaginative involvement and the tendency to become mentally absorbed in everyday activities (the Tellegen Absorption Scale).

But Burris noticed something else. Alongside game preferences, he also asked questions that sought to uncover their imaginative involvement and the tendency to become mentally absorbed in everyday activities (the Tellegen Absorption Scale).

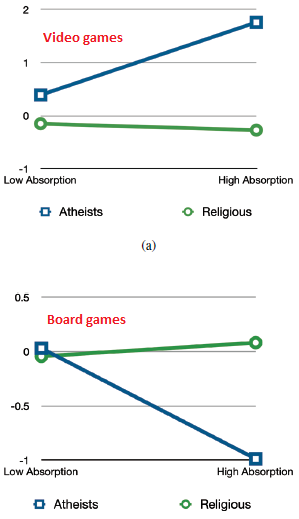

As illustrated in the graphic, what he found was that religious people had the same interest in video games and board games regardless of their tendency towards absorption. (The graphic shows the results after controlling for overall interest in gaming.)

For atheists, however, video games were more attractive and board games less attractive to those who easily become absorbed in what they’re doing.

What Burris thinks is happening is that atheists are less capable of “generating emotionally evocative internal simulations of experience” – they are less imaginative, at least when it comes to imgaining mental states and situations. This follows on from previous research he did which found that, when asked to recall emotionally-laden events in the past, “atheists’ experiences appeared to be less vivid and less emotionally evocative relative to those of religious individuals.”

They conclude that:

Even in a play context, atheists showed a much greater preference for the WYSIWYG virtual environment compared to the tabletop format wherein imagination is more central. Like tabletop gaming, many articulations of religion require that an individual behave “as if” a set of propositions concerning an unseen realm is true. If the “atheist brain” and the “religious brain” have different processing strengths and weaknesses, as Burris and Petrican (2011) suggested, then rejecting the unseen may be a logical outcome of atheists’ relative inability to generate “as if” experiences in the absence of multisensory “proof” of the sort provided by immersive, externally imposed virtual environments. Indeed, based on the results of the present research, we suspect that if Doubting Thomas were alive today, he would be an avid video gamer.

It’s a really interesting idea, and plausible, but I have a few niggling doubts. Why, for instance, does “absorption” not play a role in the preferences of religious people? And why do atheists have a greater liking for board games than religious people, if they are less capable of imaginative play?

And most importantly, I’m wondering if the preference for video games is linked to the well known phenomenon that North American atheists are more likely to be loners, and less likely to engage in group activities. I can well imagine that, among those 31 atheistic undergraduates, there were more than a few who like to shut themselves away and immerse themselves in an alternate reality provided by an online video game (Word of Warcraft, anyone?) – especially those who can become almost hypnotised by such things (which is what the Tellegen Scale measures).

In other words, religious affiliation might actually be preventing this kind of behaviour from manifesting. Or, alternatively, those who have these tendencies may shun religion.

I’m old enough to remember the good old days of Dungeons and Dragons – a kind of fantasy role playing game which involved creating imaginary worlds and acting out quests. And I also remember tat it was wildly popular among my non-religious friends (Christians hated it, of course).

![]() Burris, C., & Redden, E. (2012). No Other Gods Before Mario?: Game Preferences Among Atheistic and Religious Individuals International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 22 (4), 243-251 DOI: 10.1080/10508619.2011.638606

Burris, C., & Redden, E. (2012). No Other Gods Before Mario?: Game Preferences Among Atheistic and Religious Individuals International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 22 (4), 243-251 DOI: 10.1080/10508619.2011.638606

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.