Studies of religious belief that step outside of the Western bubble are rare, but particularly interesting for that very reason.There’s a lot of great work done that leaves you with a nagging doubt, because you can never be sure that it applies to the human race as a whole (although you can usually surmise that it does not!).

One particular gripe I have is with the idea that we invented gods to keep society functioning nicely by getting everyone to believe in a supernatural policeman. Sounds plausible, and yet when you look at many cultures outside the major monotheisms seems that their gods don’t really care much about morality. They’re interested in you giving them gifts, or looking after their waterhole, or whatever. But they don’t really care whether or not you love your neighbour.

Benjamin Purzycki, from the University of British Columbia in Canada, has been out and about among the people of the Tyva Republic in southern Siberia. Their religion is based around a mixed bag of animism, totemism, shamanism, and Buddhism. One ancient part of their religion involves the Cher eezi, the supernatural lords of resources (e.g., lakes, rivers, trees, etc.) and regions (e.g., kinbased territories, regions that are off-limits to human exploitation, and political districts).

Purzycki began by asking them simply to describe what makes a good or bad person, and also what angers or pleases the spirit masters. By way of a benchmark, he also interviewed anthropology undergraduates from the University of Connecticut – all of them believers in an omniscient god.

Overall, he found, the students were pretty clear and consistent – their God knows everything, but He cares only about the moral information (He knows what colour your shirt is, but he doesn’t care about such things). By contrast, Tyvans gave much more varied answers – suggesting that there’s no consensus about what the spirit masters know or care about.

The idea that the Spirit Masters are watching out for good behaviour just doesn’t seem to be part of their culture.

But he also asked both groups some specific questions – on questions of morality (for example, things like “e.g., Does the cher eezi of this place know if I stole from another person here?” or “…if I lied to someone when I am at home in America?”) as well as and also simple factual questions (e.g. “…that my eyes are blue?).

As well as asking the Tyvans if the spirit masters knew about these things, he also asked them if they cared (as you can see, he was interested to know if the Spirit Masters were only concerned with local misdeeds or whether they are omniscient, like the Western god).

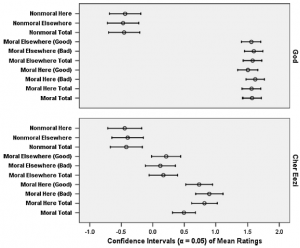

The aggregate numbers were convincing. Take a look at the graphic. It shows how concerned are the Western god and the Tyvan Spirit Masters about moral transgressions.

For the Westerners, god is concerned about all moral acts wherever they are committed. The Tyvan’s spirit masters are not only less concerned about moral transgressions, but that concern ebbs away with distance from their sacred place. Unlike the western gods, the Tyvan just aren’t omniscient.

So it seems that although Tyvan’s don’t really seem to think of moral concerns as a defining feature of the spirit masters, they still, when asked, think that they are concerned about moral behaviour.

Which is a little odd, if you think about it.

Maybe, Purzycki speculates, it’s just that Tyvan’s naturally attribute moral concerns to their Spirit Masters because that’s how other supernatural agents they know about think (e.g. “Buddha”).

To add to that, it strikes me that perhaps they just think the Spirit Master are a bit like people. Most people would not define themselves as being preoccupied by morality – though isf asked you would take a dim view of shoplifting, say.

Regardless, the implication is that nonmoral gods could provoke us into more moral behaviours – similar to the way people cheat less if they think there is a ghost in the room.

Which is intriguing but I wonder about the practical effects. Most people who lie or cheat usually believe that their behaviour is justified. It’s a small step from there to convincing yourself that the Spirit Master is on your side – especially if the terms of moral behaviour are not rigidly defined.

So, as Purzycki concludes:

…the ultimate question of whether or not various explicit conceptions of gods’ minds have particular behavioral and fitness effects requires further investigation. Is there variation in levels of prosociality for populations who explicitly moralize their deities?

Really, the problem depends a lot on the cultural context. And there’s going to be interplay between the cultural context and how the local gods come to be seen and defined. Maybe there’s more than one way to skin the “complex society” cat.

![]()

Purzycki BG (2013). The minds of gods: a comparative study of supernatural agency. Cognition, 129 (1), 163-79 PMID: 23891826

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.