I recently got a shout-out from a colleague in the history department with whom I have taught in an interdisciplinary course on several occasions. In my college’s quarterly magazine publication for “alumni, parents, and friends,” this colleague was asked to provide a brief reflection on an aspect of his experience at the college. He wrote of what it is like to walk down the hall of our beautiful center for the humanities as he heads toward his office in the back wing of the building each morning. He noted that he takes pleasure in observing some of his colleagues “doing their thing” in the seminar rooms that line the hall—I was one of three professors he mentioned by name. Noting that he doesn’t loiter or eavesdrop at the open doors of his colleagues’ classes since “that would be creepy,” he summarized his workday morning experience in the next paragraph.

Every single day I get to catch tiny, inspirational glimpses of the amazing education my colleagues are offering our students. I love walking into work because I get to see Providence College professors doing what they do best. And, trust me, they are masters of their craft.

Shortly after reading the article, I bumped into one of the other colleagues mentioned as “masters of their craft”—she and I immediately congratulated each other on our status as teaching “masters,” then began to tease various colleagues for the rest of the morning who, despite their obvious excellence in the classroom, have not achieved “masters of their craft” status.

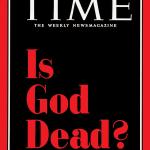

I’m currently in the very early stages of gathering my ideas and thoughts for my next book project, tentatively entitled “Nice Work If You Can Get It: Reflections on a Lifetime in the Classroom.” When it comes to the teaching profession, I am unashamedly idealistic, regularly telling anyone who will listen that I have the greatest job in the world. Actually, I don’t consider what I do to be a job. It’s a vocation, a calling every bit as sacred as that professed by the Dominican priests whom one meets every day on our campus. But I was reminded the other day that not all college professors think the same way about what they do for a living.

The current edition of The Atlantic includes an article by George Mason University economics professor Bryan Caplan entitled “What’s College Good For?,” with the following opening caption: “College students learn little, and most forget what they do learn with shocking speed. So why are we pushing ever more people into higher education?” Caplan’s article, which I read in its entirety, is adapted from his recent book The Case Against Education, which I will not read. I understand that it is trendy these days for academics to actively trash the value of what they do for a living, but I always wonder how someone who shares the same profession I love so dearly can believe so differently concerning its value than I do. In Caplan’s case, one paragraph from the middle of the article told me all I needed to know. Calling himself a “cynical idealist,” Kaplan writes that

I embrace the idea of transformative education. I believe whole-heartedly in the life of the mind. What I’m cynical about is people. I’m cynical about students. The vast majority are philistines. I’m cynical about teachers. The vast majority are uninspiring. I’m cynical about “deciders”—the school officials who control what students study. The vast majority think they’ve done their job as long as students comply.

I hate cynicism—I say that as a person who has had a more difficult time avoiding cynicism and its silent partner, apathy, over the past couple of years than in any time during my adult life. I agree with Maria Popova, who once in an “On Being” NPR interview with Krista Tippett described cynicism as “the sewage of the soul.” I’m willing to accept the label “idealist,” as long as it doesn’t imply that my ideals are disconnected with reality. In the spirit of Hillary Clinton describing herself in a 2016 debate as “a progressive who gets things done,” I prefer to describe myself as a pragmatic idealist—a person whose ideals are always tempered by and answerable to reality.

Bryan Caplan put his finger on the difference between people like him and people like me when he writes “what I’m cynical about is people.” I’m not—decidedly not. My faith directs me not to be cynical about people, as does my natural optimism. Most importantly, my real life experience, regardless of what the media shouts at me on a daily basis, is what tells me not to be cynical about people. Since much of my “real life” is spent with students, with fellow faculty, and with administrators on campus, I have a well-developed response, rooted in almost three decades of experience, to Caplan’s cynical judgment that most students are “philistines,” most teachers are “uninspiring,” and most administrators are simply mailing it in. My response? You, Professor Caplan, are full of shit.

As one might expect from an economics professor, Caplan is a number-cruncher. He provides a few survey results to support his cynicism in his article; I’m sure his book piles the numbers on with inexorable urgency. As a professor in the humanities, I respond that a good experiential anecdote outweighs any number of studies and polls. I used to laugh when one of my teaching mentors from my early years as a professor told me (when he was undoubtedly younger than I am now) that the older he got, the more he found himself slipping into his anecdotage. I don’t laugh about it any longer, first because I find the same thing happening to me and, second, because I believe that’s a good thing. Human beings are story-telling animals; we weave our realities out of stories and experiences. My expectation is that the book I hope to write will be of that sort.

After almost three decades of teaching, I have more anecdotes and stories to support my natural optimism about teaching and people than could possibly make the cut even in a book several hundred pages long. My latest story comes from my recently completed Philosophy of Knowledge course, a class with an eclectic collection of eleven students ranging across several philosophy majors and minors, a few honors students, and a handful of guys from the lacrosse team. My assumption going into every class, including this one, is that despite various stereotypes and preconceptions, I should give every student the benefit of a doubt. Each student wants to be here, wants to learn, is capable of learning, and will work hard to satisfy course requirements until proven otherwise. I am occasionally disappointed, but not very often.

At the end of the semester, several students reminisced about their class experience in their final intellectual notebook entries (the notebook is an ongoing writing assignment throughout the semester). Here are a couple of examples:

Student One:

- The best way I can describe this class, is that it allowed me to better channel the exhausting ruminations that go on inside my head . . . Overall, I think the world has gotten a lot less “black and white” and a lot less bland for me over the course of the semester. I have discovered that even if my beliefs orient me towards a given conclusion there is no weakness in saying that I may be wrong or even hoping that I am wrong. Sure it is noble for a human being to stick to their principles, but it is also an injustice to the self if we let these principles completely wipe out any possibility for change.

Student Two (who had to beg me to let him into the class a week after the semester started):

- I walked out of every class discussion, and this is not an exaggeration, feeling clear headed and more open to the world. Although I was quiet in the beginning, I was still always engaged mentally. As the semester progressed and I opened up I felt as if I was expressing myself honestly, something that I often feel I cannot do properly . . . As I move forward in my life I plan on keeping philosophy close to my heart, no matter what I do. For it truly does give me life and a more exciting existence . . . [Philosophy] allows me to see the mystery it allows me to view life as a question—one that needs an answer . . . Transferring over to your class was one of the best decisions I made at Providence College. Thank you so much for everything.

Whenever I feel overwhelmed by the demands of what I do (which does happen on occasion), the faces of students such as these pass in front of me. “What’s College Good For,” Professor Caplan? Not much, perhaps, if one relies solely on polls and numbers. But I’ll take a transformed life or two over your numbers every time.